[ad_1]

Receive free Indian economic system updates

We’ll ship you a myFT Daily Digest electronic mail rounding up the newest Indian economic system information each morning.

Riyaz Ahmed’s mill on the outskirts of Mysuru, a part of a fertile agricultural belt in southern India, is stacked with gunny baggage stuffed with an unexpectedly valuable commodity: rice.

Prices for rice, tomatoes and different staples have surged in current weeks because the erratic arrival of India’s annual monsoon has upended agricultural manufacturing. While heavy rains in some areas washed out crops, their delayed arrival right here and elsewhere is stoking fears of poor harvests and even greater costs.

“The monsoon is late . . . and now water is short”, mentioned Ahmed, 69, who has been milling rice for almost 30 years. “Everyone from the lowest to the highest earners is suffering, including me.”

This surge in meals inflation has turn out to be a swelling supply of concern for Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s authorities, which final week banned exports of several rice varieties after weeks of public anger over excessive costs.

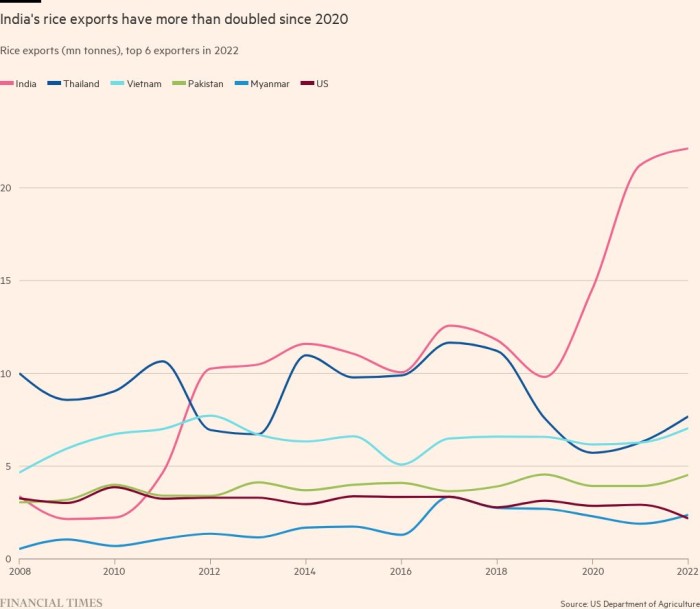

The transfer despatched shocks across the globe, with the IMF calling on Modi’s authorities to reverse its “harmful” resolution. India is the world’s largest rice exporter, and plenty of international locations depend upon it for shipments of the staple.

Analysts mentioned controlling meals costs had turn out to be a precedence for Modi’s Bharatiya Janata social gathering because it ready for a collection of essential elections, together with a number of state polls this 12 months and the nationwide vote in lower than 12 months.

“When it comes to food trade, no government — Modi or anyone — takes a longer-term view,” mentioned Avinash Kishore, a senior analysis fellow on the International Food Policy Research Institute. “Poorer Indians’ pockets are already being pinched [and] with grain prices going up, no government would want to take that risk, even in a normal year — and this year is an election year.”

The monsoon, which passes throughout India from June to September, typically triggers volatility in food prices. Yet scientists warned that these important rains have gotten much less dependable, resulting in extra frequent flooding in some areas and droughts in others as local weather change alters once-predictable climate patterns.

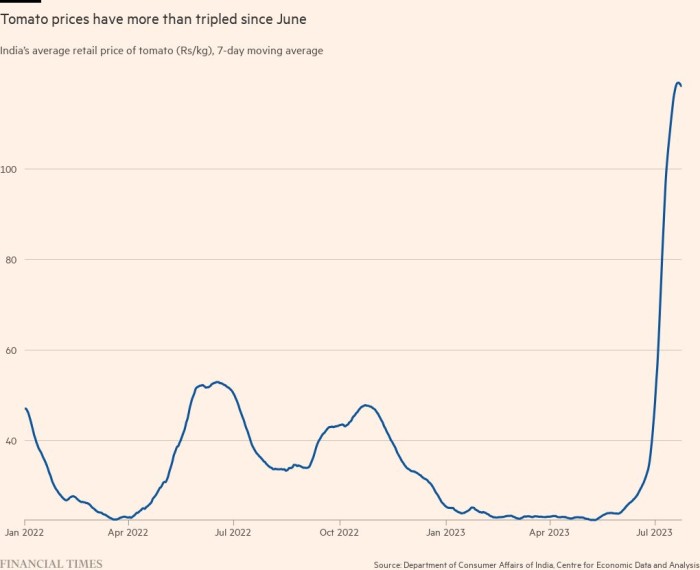

This season has been tumultuous for meals markets. Tomato costs have risen about 400 per cent since final month after torrential rains harm the crop, whereas the price of rice has elevated 11.5 per cent since final 12 months.

“How to buy? That’s the question I’m asking myself,” mentioned Jeetu Singh, a 32-year-old migrant labourer at a wholesale vegetable market close to Mysuru in India’s south-western Karnataka state. “Tomato, rice, dal — everything has gone up.” Another shopper, Jayalakshmi, mentioned she had been slicing again on lentils, oil and different necessities to be able to afford her payments.

Though the patron inflation charge of 4.8 per cent in June stays inside the Reserve Bank of India’s goal vary, the central financial institution warned this month that the surge in meals costs confirmed “the fight against inflation is far from over”.

The authorities argued that the rice export ban, which applies solely to non-basmati white rice and accounts for about 40 per cent of the nation’s exported varieties, would shield home shoppers whereas permitting cereal to circulate into the worldwide market, serving to Indian farmers.

Authorities have responded to the tomato value surge with all the pieces from subsidies to a “hackathon” designed to enhance the provision chain.

Higher meals costs have prior to now proved politically precarious for incumbent Indian governments, with analysts attributing well-known election upsets to anger over excessive onion costs.

India’s opposition has seized on the newest surge to assault Modi’s authorities. Mallikarjun Kharge, president of the Indian National Congress, the principle opposition social gathering, blamed vegetable value inflation on the BJP’s “loot” and “greed”.

“The public has become aware and will answer your hollow slogans by voting against the BJP,” he mentioned this month.

The BJP stays the favorite in nationwide elections, that are due within the first half of subsequent 12 months, however faces a collection of probably powerful state polls in Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh later this 12 months. It suffered a significant setback in May, losing control of Karnataka to Congress.

One of Congress’s marketing campaign guarantees in Karnataka was to double the quantity of free rice given to low-income households. Its new state authorities this month began a money switch scheme designed to finance consumption of the grain.

The BJP’s restrictions on rice exports, designed to appease shoppers, have upset one other highly effective constituency: farmers, lots of whom stood to learn from greater costs.

Rajpal Singh, a rice farmer within the north-western state of Punjab, dismissed the export restrictions as a gimmick to handle public notion forward of the elections. “The government is trying to keep food prices under control because . . . food prices matter the most to a majority of voters,” he mentioned. “They think public memory is short.”

Swamy Ok, a 68-year-old rice farmer in a village close to Mysuru, mentioned he remained loyal to Modi though he loathed Karnataka’s erstwhile BJP authorities. But he mentioned his endurance with the social gathering was operating skinny.

“Politicians keep saying that farmers are the backbone of the country, but that backbone has long been broken,” he mentioned. “They put us on posters, but give us nothing.”

[adinserter block=”4″]

[ad_2]

Source link