[ad_1]

What we now have is a classic “western-style” demand slowdown that post COVID-19 has turned into a full-fledged recession bereft of consumption and investment demand.

What we now have is a classic “western-style” demand slowdown that post COVID-19 has turned into a full-fledged recession bereft of consumption and investment demand.

India has never experienced negative economic growth since 1979-80, and before that in 1972-73, 1965-66 and 1957-58. All these were drought years with 1957-58 also registering a significant balance of payments (BOP) deterioration and 1979-80 witnessing the second global oil shock following the Iranian Revolution.

The real GDP decline of 5-10 per cent that various agencies are projecting for 2020-21 would be the country’s first ever not triggered/accompanied by an agricultural or a BOP crisis.

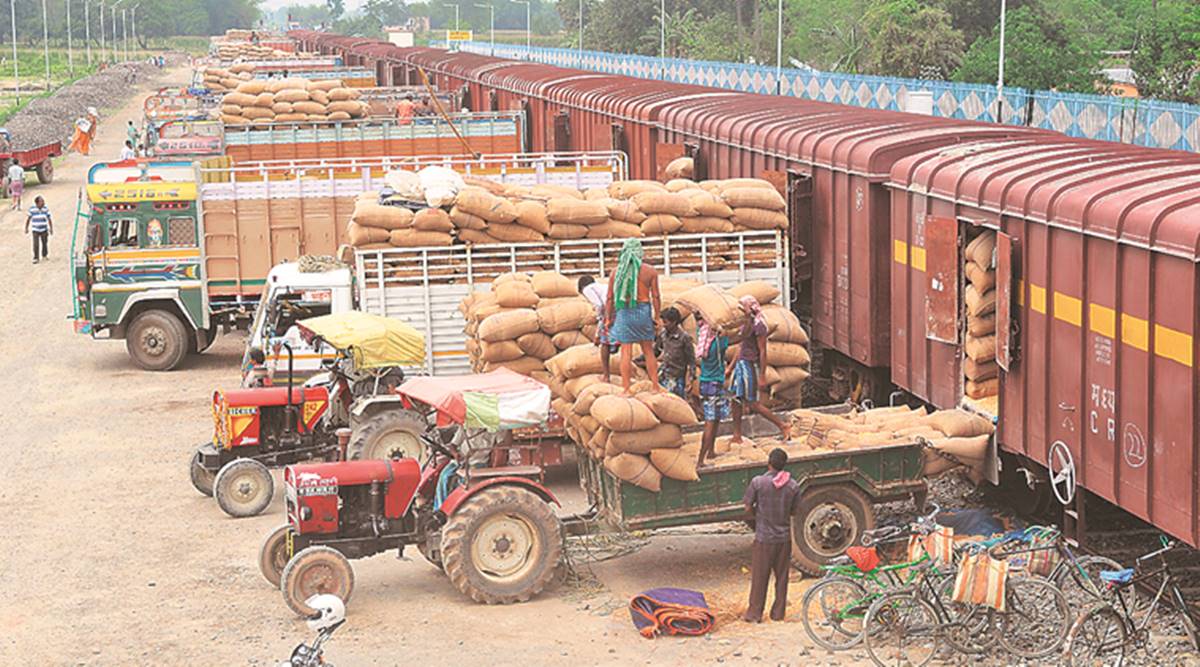

This time round, not only have farmers harvested a bumper rabi crop, and look set to repeat it in the ongoing kharif season, public cereal stocks at 94.42 million tonnes as on July 1 were also 2.3 times the required level. The January-March 2020 quarter was the first in 13 years to have recorded a current account BOP surplus. June even saw a surplus on the merchandise trade account for the first time after January 2002. Foreign exchange reserves were at an all-time high of $538.19 billion on August 7, rising by $60.38 billion since end-March amidst the novel coronavirus and the lockdown.

That makes the current contraction totally different from the previous ones which were “supply-side” induced. There’s no shortage today of food, forex or even savings: Aggregate deposits with commercial banks as of July 31 were Rs 14.17 lakh crore or 11.1 per cent higher than a year ago. The closest parallel one could draw is with the 2000-01 to 2002-03 period of the Atal Bihari Vajpayee-led government. The Food Corporation of India’s (FCI) grain stocks in July 2002 were 2.6 times the buffer norm and the country ran current account surpluses in 2001-02 and 2002-03. But the economy didn’t contract then; growth merely fell from 8 per cent in 1999-2000 to an average of 4.5 cent during the next three years.

What we now have is a classic “western-style” demand slowdown that post COVID-19 has turned into a full-fledged recession bereft of consumption and investment demand. Households have cut spending as they have suffered income, if not job, losses. Even those with jobs are saving more than spending because they aren’t sure when their luck would run out. The same goes with businesses. Many have shut or are operating at a fraction of their capacity and pre-lockdown staff strength. The ones still making profits are conserving cash. If at all they are investing, it is to buy out struggling competitors and not to create new capacities. Just as households are uncertain about jobs and incomes, firms don’t know when demand for their products will really return.

This demand-side uncertainty and the resulting economic contraction is something new to India. And it stands out in a situation where food stocks and forex reserves are at record highs. Meanwhile, banks are also facing a problem of plenty. While their deposits are up 11.1 per cent, the corresponding credit growth has been just Rs 5.37 lakh crore or 5.5 per cent. With very little credit demand, the bulk of their incremental deposits are being invested in government securities, which have increased year-on-year by Rs 7.21 lakh crore or 20.3 per cent.

In demand recessions, there are hardly any villains. No one is hoarding food, driving up oil prices or shorting the rupee. You cannot blame consumers for not spending. Nor can employers be faulted beyond a point for sacking their staff. Everyone is being perfectly rational and virtuous. In most cases, the competence, commitment or integrity of individuals isn’t under question. To be moralistic is to insult the millions of migrant labourers thrown out of work and entrepreneurs who have lost everything they had put into their businesses. This is a purely economic problem — of people with even incomes not spending and savings not getting invested. At some point when all this reduced spending and investments leads to a further contraction of incomes, it is bound to squeeze out savings as well.

Everybody knows the solution. If there’s anybody at all that can spend and invest today, it is the government. There are two probable reasons, though, why it isn’t doing that. The first is the expectation/hope that once the worst of the pandemic is behind us, people will start spending and businesses, too, will spring back to life. However, this assumes the economy wasn’t doing all that badly previously and that the lockdown hasn’t caused too much of permanent damage. The truth is that growth had already slid to 3.9 per cent in 2019-20 and we don’t know how many solvent firms would remain even after the COVID uncertainties lift.

The second reason for not doing much is, of course, the state of government finances. In 2007-08, the year preceding the global financial crisis, the Centre’s fiscal deficit was only 2.5 per cent of GDP, whereas it stood at 4.6 per cent in 2019-20, excluding “off-budget” financing of expenditures through borrowings forced on the likes of FCI. The space for a fiscal stimulus, in other words, is very limited compared to that time.

But it is equally a fact that between 2007-08 and 2019-20, the Centre’s outstanding debt-GDP ratio has come down from 56.9 to 49.25 per cent. So has general government debt, which includes the liabilities of states, from 74.6 to 69.8 per cent. Economists such as Olivier Blanchard have shown that public debts are sustainable provided governments can borrow at rates below nominal GDP growth (that is unadjusted for inflation). The latter averaged 11.1 per cent during the Narendra Modi government’s first term from 2014-15 to 2018-19. As against this, the weighted average interest rate on Central government securities ruled between 6.97 per cent in 2016-17 and 8.51 per cent in 2014-15. Only with nominal GDP growth falling to 7.2 per cent in 2019-20, and most likely zero this fiscal, has the Blanchard debt sustainability formula come under threat.

The Modi government can take lessons from the Vajpayee period when the weighted average cost of Central borrowings more than halved from 12.01 per cent in 1997-98 to 5.71 per cent in 2003-04. We are seeing something similar happening: In the last four months, yields on 10-year Indian government bonds have softened from 6.5 to 5.9 per cent and even more for states — from 7.9 to 6.4 per cent — despite massive fiscal slippages. Interest rates will fall further as banks have nobody to lend to.

Governments should borrow and spend. They need worry only about GDP growth, real and nominal.

harish.damodaran@expressindia.com

📣 The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest Opinion News, download Indian Express App.

© The Indian Express (P) Ltd

[ad_2]

Source link