[ad_1]

Tanisha Long founded an unofficial Black Lives Matters chapter in Pittsburgh. She is actively campaigning for Joe Biden to win Pennsylvania, a key swing state in the election.

Nate Smallwood for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Nate Smallwood for NPR

Tanisha Long founded an unofficial Black Lives Matters chapter in Pittsburgh. She is actively campaigning for Joe Biden to win Pennsylvania, a key swing state in the election.

Nate Smallwood for NPR

Tanisha Long expects to be busy in the run up to the 2020 election.

For the next six weeks, Long, who founded an unofficial Black Lives Matter chapter for Pittsburgh and Southwestern Pennsylvania, plans to make get-out-the vote videos, host mail-in voting webinars and work to enfranchise eligible incarcerated people in order to turn out voters she says “no one’s talking to anymore.”

Long’s concern is this: she sees the campaign for Democratic nominee Joe Biden making the same mistakes in Pennsylvania that Hillary Clinton made in 2016. Long believes the Biden campaign is failing to do enough to engage traditional Democratic constituencies.

“I just can’t have that happen again, it’s really stressing me out,” she says.

Donald Trump famously lost the popular vote in 2016 by over 2.8 million votes but secured a victory in the electoral college by winning razor thin margins in key swing states, including Wisconsin, Michigan, Florida and Pennsylvania. Both the Trump and Biden campaigns are focused on these states, looking to get support from voters who either sat out 2016 or might be persuaded to vote for the other side. In Pennsylvania, that has meant a disproportionate interest in white suburban voters. Trump won them over by larger margins than expected in 2016, including just outside Pittsburgh in Washington County.

Sheridan Newsome, 21, walks by a mural in Pittsburgh’s Homewood neighborhood. Despite receiving the consistent support of Black communities, many voters here say Democratic leaders have largely failed to effectively address enduring problems like police violence, discrimination and income inequality that have disproportionately hurt Black residents in Pittsburgh.

Nate Smallwood for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Nate Smallwood for NPR

Sheridan Newsome, 21, walks by a mural in Pittsburgh’s Homewood neighborhood. Despite receiving the consistent support of Black communities, many voters here say Democratic leaders have largely failed to effectively address enduring problems like police violence, discrimination and income inequality that have disproportionately hurt Black residents in Pittsburgh.

Nate Smallwood for NPR

But a tightly contested 2020 election in Pennsylvania could be decided at least in part by people outside those suburbs. This includes Pittsburgh’s Black residents, 22 percent of the city’s population, who are usually considered a reliable Democratic constituency.

And yet, Democrats could have their work cut out for them.

Despite receiving the consistent support of Black communities, some voters here say Democratic leaders have largely failed to effectively address enduring problems like police violence, discrimination and income inequality that have disproportionately hurt Black residents in Pittsburgh.

‘For voting, it takes a personal touch’

Writer Damon Young, 41, is a life-long Pittsburgher who founded the website Very Smart Brothas and wrote the memoir What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Blacker. He says he was alarmed — but not surprised — by a widely publicized report out of the city of Pittsburgh’s Gender Equity Commission last year that found that while white Pittsburgh residents have better health outcomes and quality of life than the national average, the city is one of the worst in the country for Black people, and particularly for Black women. Black residents deal with higher infant mortality rates, lower wages, worse educational outcomes, and higher incidences of cardiovascular disease and cancer. All this in a city that often ranks on the list of the country’s most livable cities.

“That’s the thing,” Young says.

For Young, this kind of long-term inequality can make it hard to persuade Black residents to turn out.

“It can be a hard sell. If someone says ‘We’ve had nothing but Democratic mayors in Pittsburgh my entire life, and well, it doesn’t affect me. There’s still this violence happening, there’s still no jobs, the schools are better in the white communities, that hasn’t changed with Barack Obama being president or Bill Peduto being mayor. So why should I care?’ ” he says.

Hip-hop artist Jasiri X is working to help people vote with a new nonprofit he helped create called 1Hood Power.

Steve Inskeep/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Steve Inskeep/NPR

Hip-hop artist Jasiri X is working to help people vote with a new nonprofit he helped create called 1Hood Power.

Steve Inskeep/NPR

Young’s friend Jasiri X, the 37 year-old hip hop artist who runs the community organization 1Hood, says he used to vote as an independent. Then he realized that Pittsburgh’s strong Democratic party history means that the primaries are where the important politics happen, so he had to become a Democrat to vote in the local elections that mattered.

Though he’s now a Democrat, he sees the party’s establishment as detrimental to Black Pittsburghers.

“We’re comfortable doing things the way they are but that’s harmful to me as a Black person. It’s been harmful to my community for years. So I’m somebody looking for bold, innovative change,” he says.

To help push the party in a more progressive direction, Jasiri X is working to help people vote with a new nonprofit he helped create called 1Hood Power.

“What I didn’t see in 2016 was an investment in Black-led organizations to actually speak to Black people, to have those important conversations, to get Black people to the polls,” he says. “For voting, it takes a personal touch.”

Young and Jasiri X both plan to vote for Biden, though they aren’t enthusiastic about him or his running mate, Kamala Harris.

Simply put, Young believes his life depends on Biden defeating Trump in November. And it’s up to white voters to get it done.

“We talk about how Black women, Black voters, Latino voters will decide it. No. White people will decide the election,” he says. “If he wins again, it’s not because we weren’t engaged. It’s not because we didn’t come out. It’s because white people came out and ignored the four years of evidence of Donald Trump being an unrepentant racist and a misogynist and a terrible businessman.”

‘A fighting chance’

Lisa Cunningham, 58, has lived in the Hill District, one of Pittsburgh’s historically Black neighborhoods, for about 45 years. She’s worried about a lot of the things Young and Jasiri X identified as issues that might lead people to be reluctant to vote for Democrats, or to vote at all.

“Jobs, fairness, economic disparities, racism. You have people sitting on top of us up there and they’re looking down on us down here,” Cunningham says, gesturing to the sky scrapers downtown. But her enthusiasm for Biden — and for voting — remains strong.

“I adore him,” she says about Biden, “I know he will give us equality and he will give us a fighting chance.”

Cunningham says she’d rather risk catching the coronavirus to be able to cast her ballot in person than trust mail-in voting, even though her daughter had COVID-19.

Pennsylvania State House Rep. Summer Lee was first Black woman from western Pennsylvania elected to the Pennsylvania state house.

Salwan Georges/The Washington Post via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Salwan Georges/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Pennsylvania State House Rep. Summer Lee was first Black woman from western Pennsylvania elected to the Pennsylvania state house.

Salwan Georges/The Washington Post via Getty Images

“There’s nothing that can keep me from it. I’m going in there, COVID and all, to cast my vote,” she says.

‘I can’t lead folks to a place that I’m not willing to go myself’

Summer Lee, 32, decided to run for office in 2018. She ran in Braddock, Pa., a town in the greater Pittsburgh area and one of the few that still has an active steel mill.

“We don’t get a lot of Black women running for office. We don’t get a lot of progressive folks running for office in western Pennsylvania,” she says, “I can’t lead folks to a place that I’m not willing to go myself.”

Lee, a lawyer, unseated Democratic incumbent Paul Costa who had been in office for 20 years. She became the first Black woman elected to represent Southwestern Pennsylvania in the state house. She campaigned against a fracking proposal in Braddock and went door to door speaking with people about environmental racism, cyclical poverty and racial and economic justice.

But when she was running as an incumbent in the Democratic Party primary in early 2020, the Allegheny County Democrats endorsed her opponent, a white man. Lee won the primary handily anyway, with 77 percent of the vote, all but assuring a second term.

Lee’s differences with the Democratic party establishment are profound. She was a delegate at this summer’s virtual Democratic National Convention and voted against the party’s official platform.

United States Steel’s Edgar Thomson Plant seen in Braddock, Pa., on Sept. 12. Rep. Lee represents this area, which still has an active steel mill.

Justin Merriman/Bloomberg via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Justin Merriman/Bloomberg via Getty Images

United States Steel’s Edgar Thomson Plant seen in Braddock, Pa., on Sept. 12. Rep. Lee represents this area, which still has an active steel mill.

Justin Merriman/Bloomberg via Getty Images

“I don’t believe it’s a platform that meets the moment,” she says. Though she differs with Biden on many issues — from fracking to Medicare For All — she fully intends to vote for him.

“If we’re fighting for a healthier environment, if we’re fighting for more equitable funding for schools, for police accountability and criminal justice reform, whatever it may be, we have an obligation to move us closer to that, not farther away,” she says.

Looking for unity, diversity and strength

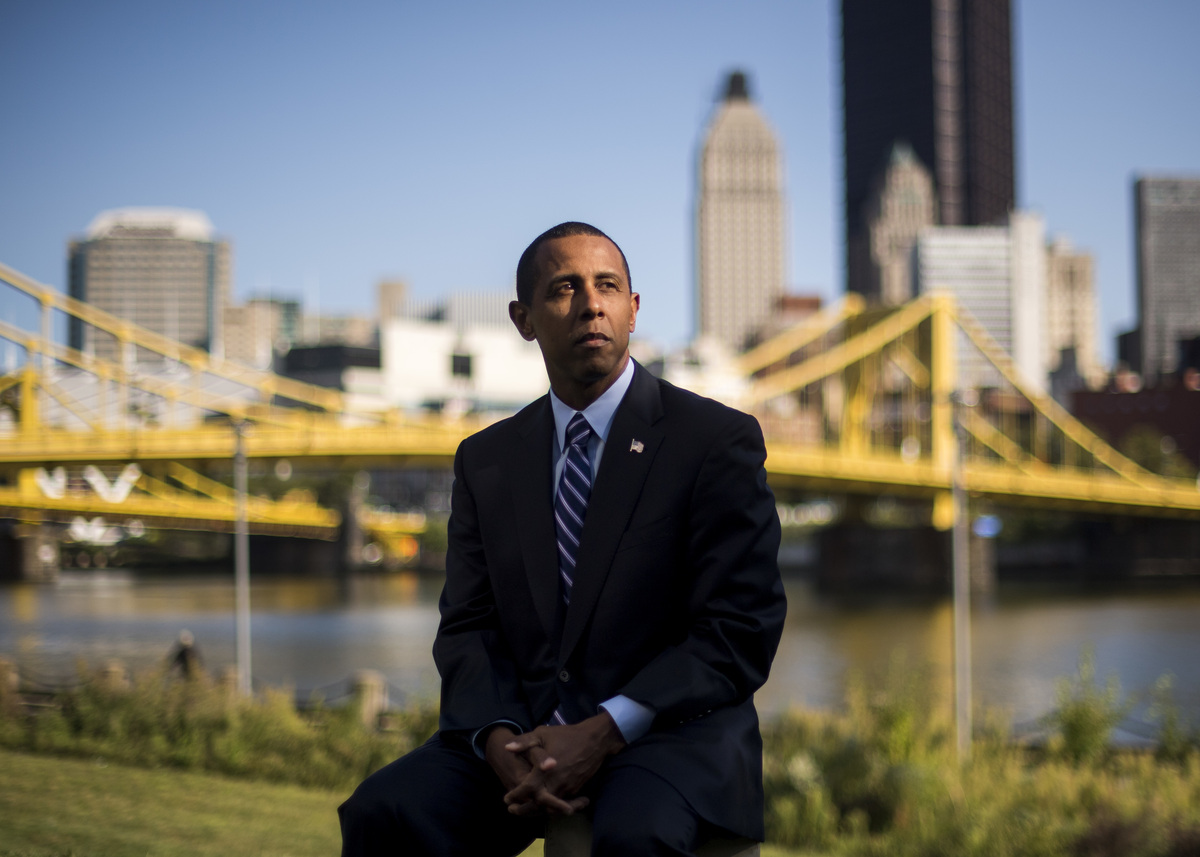

Republican Lenny McCallister says he could not vote for Donald Trump in 2016 because of his Christian faith. But he also can’t imagine ever voting for Biden.

Nate Smallwood for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Nate Smallwood for NPR

Republican Lenny McCallister says he could not vote for Donald Trump in 2016 because of his Christian faith. But he also can’t imagine ever voting for Biden.

Nate Smallwood for NPR

Lenny McCallister, 48, grew up in the Penn Hills area of Pittsburgh, where he still lives. His father was raised in East Liberty.

He says his anti-abortion and pro-school choice beliefs are cornerstones of his politics. He ran for Congress in 2016 as a Republican in Pennsylvania’s 14th district (he lost) after securing the nomination in a write-in campaign, but says he could not bring himself to vote for Trump because of his faith. He made that decision before the election “when Mr. Trump said in 2015 that he never felt that he had to ask God for forgiveness, just figured he would fix it himself.”

As a Christian, he says, he understands that “you can’t fix everything yourself.”

“When I heard that,” he says, “that was enough for me to take a step away.”

But McCallister also can’t imagine ever voting for Biden, in part because a crime bill he shepherded through the Senate in 1994.

“His 1994 crime bill disproportionately impacted communities such as Homewood, where literally generations of fathers and mothers spent disproportionate amounts of time in jail,” he says.

William Allen walks by a mural in the Homewood neighborhood of Pittsburgh.

Nate Smallwood for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Nate Smallwood for NPR

William Allen walks by a mural in the Homewood neighborhood of Pittsburgh.

Nate Smallwood for NPR

As one of few active Black Republicans in Pittsburgh, Lenny admits that the party has a problem embracing diversity.

“There’s not a lot of Republicans that try to connect to different and diverse portions of the nation. I think that when we say ‘we love America,’ we love America in the sense that we love what we’re familiar with. We don’t love Damon Young or Summer Lee when they disagree with us,” he says.

And McCallister is troubled by many of the same problems facing his city, his community and his nation as Young and Lee: racial health disparities, discrimination and police violence.

“Damon Young is never going to be my enemy. Summer Lee, as a hardcore, left-leaning Democrat is never going to be my enemy,” he says.

Ariel Worthy, government and accountability reporter at WESA, contributed to this story.

[ad_2]

Source link