[ad_1]

Poland became the first country to put a video game, “This War of Mine”, on the official school reading list.

Poland became the first country to put a video game, “This War of Mine”, on the official school reading list.

exPress Start is a weekly online column on the intersection of gaming and culture. Level up with Gaurav Bhatt every weekend as he explores the creative and competitive sides of video games.

Millennials will remember sneakily loading up ancient DOS-based video games in computer labs at school, or fielding ultimatums from parents back home: “Books or games?”

In Poland, at least, students now can audaciously respond, “why not both?”

Last month, Poland became the first country to put a video game on the official school reading list. ‘This War of Mine’, a wartime survival game developed by 11 Bit Studios, will be made available to students of sociology, ethics, philosophy, and history during the 2020-21 academic year.

“Poland will be the first country in the world that puts its own computer game into the education ministry’s reading list,” Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki told Polsat News. “Young people use games to imagine certain situations (in a way) no worse than reading books. By incorporating games into the education system, we will expand our imagination and bring something new to the culture.”

While games have long been recognised to be instrumental in sharpening general cognitive skills (attention span, reflexes, and memory), this is the first instance of a title being recommended as a reading subject. Released in 2014, This War of Mine received acclaim for its realistic study of the human cost and civil collapse of war, and had sold more than 4.5 million units in April 2019.

The gameplay mechanics of the 2015 video game “This War is Mine”.

The gameplay mechanics of the 2015 video game “This War is Mine”.

“I’d say this is an important moment for all the game industry all around the world. Why? Because on a government level a game is acknowledged to be a work of culture, as potentially influential as a book,” Pawel Miechowski, senior writer and partnerships manager at Poland’s 11 Bit Studios, tells The Indian Express. “This is a milestone moment, a breakthrough when we can stop saying about games that they’re IT products or just entertainment and agree that they are work of culture.”

It was at the Game Developers Conference that the game’s art director Przemyslaw Marszal talked about a creative goal to make games which could be studied in school. The notion gained momentum as the team participated in several exhibitions and cultural events, and finally met the government officials last year. The idea reached the offices of the Minister of Education and the Prime Minister, and both gave it a green light.

War! What is it good for?

Numerous games have used ‘wars’ and ‘battlefields’ as window dressing to justify racking up ‘kills’ and piling dead bodies, with a Hollywoodised focus on spectacle. But instead of putting you in the shoes of a supersoldier, ‘This War of Mine’ has you controlling survivors holed up in a rundown building.

Food, potable water, meds, beds and cots are luxuries. You can set up makeshift arrangements or send one of your characters out to scavenge at night, though the presence of militia, soldiers, looters or other survivors means any supply run could be your last. The characters have special skills tied to their backstories. A former football player is better suited to venture outside. A good cook can boost morale.

There are no fixed narratives or objectives to gamify the experience. The objective is to stay alive, you “win” when the war is over, and nobody knows when that’d be. There are murmurs of an international peacekeeping intervention, but with no specific timetable. Till then, if starvation or injury doesn’t get you, heartbreak will. (In one of the game’s many gutwrenching choices, I decided to steal resources from an elderly couple to save my group. They saw as I robbed their house of food and medicine, and the sheer barbarism of the act sent my character into a depression to the point that I couldn’t control him anymore).

The charcoal-stylised 2D art and moody music add to the haunting aesthetic. The titular war is unspecified, and the game takes place in a fictional setting of Graznavia, Pogoren, but the developers draw on the experiences of the Bosnian people during the Seige of Sarajevo in the 1990s — including their grandparents.

“The game was supposed to be a universal story, not related to specific historic events, so we looked at and gathered stories from various conflicts. Yet, the basic inspiration was the events that took place during the Siege of Sarajevo and then we looked wider at the Yugoslavian Wars and then even wider at other 20th century conflicts – the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, the Battle of Grozny, the Battle of Aleppo in Syria and others,” Miechowski says. “Many stories were just personal family stories that team members shared with the team, stories of our grandmothers and grandfathers who survived the war. This is why this game became a very personal project.”

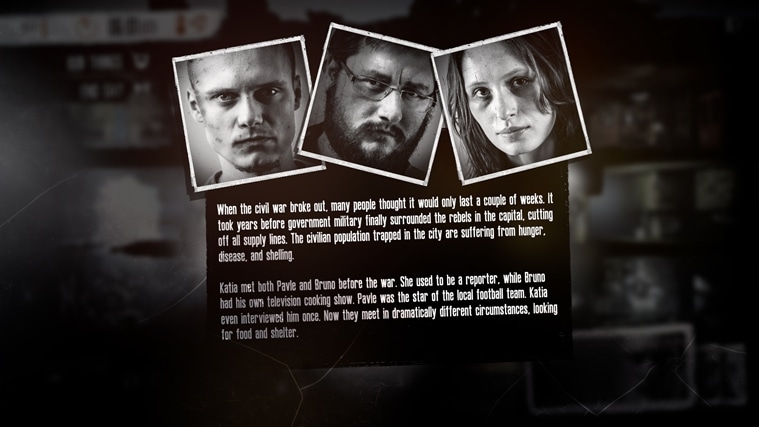

The characters of the 2015 video game “This War is Mine”.

The characters of the 2015 video game “This War is Mine”.

Showing the misery of war thus was an objective from the beginning.

“Our big goal was to present how people live, what is the cost of staying human, what is the cost of saving one’s dignity when the horrible times such as war surround people. And it wouldn’t be possible without simulating war to the extent we could simulate in a game. So there is violence, there is starvation, there are diseases and nervous breakdowns and there is death. We had to present players with such situations to show how war brutal can be… In such understanding, the game is an anti-war manifesto.”

Gaming in Poland

Since its release, 11 Bit Studios have licensed the game free of cost to educational institutions in Norway, USA, Germany, Australia etc. What is it about the harrowing game that makes it work as an academic tool?

“First, it’s an environment in which a player can tell her/his own story. So the ancient teachers’ question ‘what did the author have in mind’ can be replaced with new ‘what did you have in mind while making such decisions’,” says Miechowski. “Secondly, the game is not moralising, it just gives you the freedom to act good or evil and as such can be a perfect tool to discuss ethics. That’s where interactivity of games unveils its great potential.”

Dr Dominika Urbanska-Galanciak, who has authored numerous theses on the culture of video games, praises This War of Mine for the educational value but also illustrates the artistic appeal to students.

“The game is an example that shows that the work of art requires a consistent style. In this case, the combination of story, sound and dark-coloured images strengthens the emotional value of the game,” she says.

Dominika, whose adventures with gaming began with the Commodore and Atari consoles in the 80s, is the managing director at the Polish Association of Entertainment Software Developers and Distributors (Spidor). One of the main functions of the association is to provide teachers and parents with new valuable information on how to use video games in education, as well as promoting the PEGI classification system (think suitability ratings for movies) and parental control tools.

“I have been working in the association for over 10 years and I see how the parents’ approach to using games by children is changing. According to the Polish Gamers Research, 35 per cent of parents play games with their children. Over half of the parents who took part in the research are setting parental controls on the devices their children are playing on,” says Dominika. “Of course, we can look at it so that 45 per cent of parents still do not use parental control tools and this is the group to which our association targets the campaigns. As a mother of a young gamer, I know how important is to be involved in all kinds of entertainment.”

Pawel Miechowski is a senior writer and partnerships manager at the 11 Bit Studios.

Pawel Miechowski is a senior writer and partnerships manager at the 11 Bit Studios.

Studies estimate that roughly half of Poland’s 3.8cr population plays video games. Universities, both private and government, teach game programming and design studies. Miechowski, who believes “This War of Mine played quite an important role in games being recognised as work of culture”, says the medium is now on par with other forms of entertainment.

“Nowadays, 40-year-olds are people who grew up with games all around them. For these people, myself included, games are something normal like TV or a newspaper so as long as I know what content is in a game, I don’t have any problem with my kids playing games. In fact, my daughter is a huge fan of Open Transport Tycoon Deluxe,” says Miechowski. “On the other hand are the people who generally don’t try games and their perception might be taken from other media, where games are still pictured as a source of stupidity or what’s worse, a source of aggression.”

Doing away with the either/or relationship between schools and video games is a start.

📣 The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest Technology News, download Indian Express App.

© IE Online Media Services Pvt Ltd

[ad_2]

Source link