[ad_1]

Blockchain in Supply Chain: Article 5

One benefit of blockchain includes its ability to harness the

power of smart contracts.

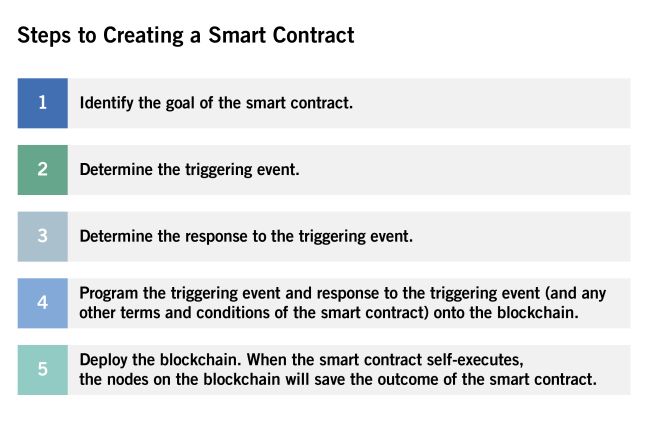

What is a Smart Contract?

Although the term “smart contract” sounds like a legal

instrument, a smart contract is actually a computer program that

performs a task when triggered by the occurrence of a predetermined

event. Smart contracts live on blockchain, which processes

the terms of the smart contract, thereby enabling the smart

contract to automatically execute the coded task when the

triggering event occurs.

Nick Szabo, a computer scientist and cryptographer who coined

the term “smart contract,” likens a smart contract to a

vending machine.1 A consumer

inserts money into a vending machine (i.e., satisfies the

condition of the contract), and the vending machine automatically

dispenses the treat (i.e., honors the terms of the

“contract”).

Oracles

In order to trigger the automatic performance of a function, the

smart contract uses “oracles” to receive information from

the outside world.

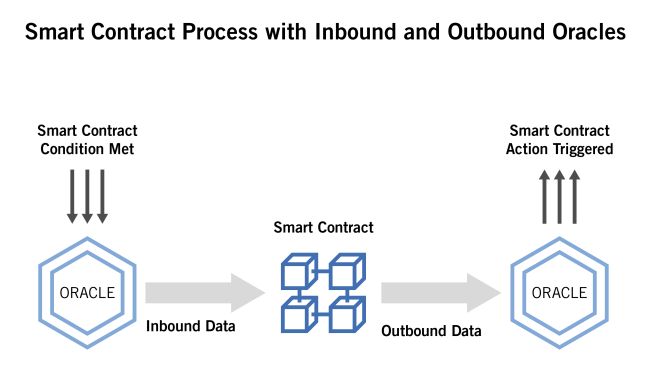

Inbound vs. Outbound Oracles

An oracle can provide data from the outside world for

consumption by the smart contract living on the blockchain (an

“inbound oracle”) or allow smart contracts to send data

to the outside world (an “outbound oracle”). As an

example of the latter, an IoT-enabled lock functions as an outbound

oracle when the smart contract triggers the lock to unlock

automatically if a party transacts a certain payment across the

blockchain.

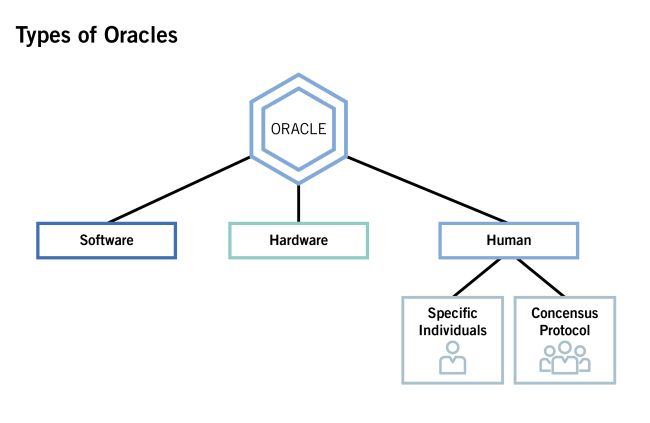

Types of Oracles

Types of oracles include hardware, software, and human:

- Software Oracles. Software functions as an

oracle by connecting smart contracts to online data sources, such

as temperature, commodity prices, and transportation delays. - Hardware Oracles. Hardware oracles include

pieces of equipment that communicate real-world information to the

smart contract. RFID sensors, for instance, can detect

environmental changes that link to blockchain to trigger a smart

contract. - Human Oracles. Humans act as oracles when they

provide real-world information to a smart contract, often with

cryptography in place to ensure the proper individual provides the

information. Another human-based approach to oracles uses a

consensus protocol, meaning that different humans vote on the input

to provide to the oracle. In any case, using a human oracle

introduces the potential for human error. A party may nonetheless

opt to use a human oracle when a decision requires subjectivity or

when the nature of the triggering event makes continuous monitoring

difficult.

In order to strengthen the trust of the oracle system, supply

chain members can use a combination of oracle types for the same

smart contract.

Examples of Smart Contracts for Supply Chain

In supply chain, smart contracts are particularly useful for

releasing payment, recording ledger entries, and flagging a need

for manual intervention.

- Releasing Payment. A party could use a

smart contract as a means to automatically release payment upon the

satisfaction of a condition. For example, two parties, such as a

manufacturer and a supplier, could set up digital wallets and a

smart contract in order for the manufacturer to pay the supplier

for the purchase of goods. After the manufacturer inspects and

accepts the goods, the smart contract would automatically move cryptocurrency from the manufacturer’s

digital wallet to the supplier’s digital wallet to effect

payment. - Recording Ledger Entries. A party could write

a smart contract to record to a blockchain ledger if some specified

event occurs or does not occur. For example, if an IoT- enabled

device detects the opening of a container during transit, a smart

contract could automatically record this information. A party may

find such monitoring particularly useful for goods that require a

tight chain of custody, such as with the transport of

pharmaceuticals. - Flagging a Need for Manual Intervention. Smart

contracts are also useful for flagging the occurrence of an event

that requires manual intervention. For example, for

temperature-sensitive products, a smart contract tied to

temperature monitors could alert all concerned parties if an

out-of-range temperature occurs. This would allow the parties to

promptly take action to correct the temperature, conduct an

investigation into the reason for the out-of-range temperature and,

when necessary, pull the affected products (and only the affected

products) from the stream of commerce.

When is a Smart Contract a “Contract” from a Legal

Perspective?

A smart contract may constitute a legal contract if the smart

contract contains the elements of valid offer and acceptance, as

well as adequate consideration. The general principles of

contract law define an offer as a manifestation of willingness to

enter into a bargain2 and

acceptance as an agreement to that offer,3 while consideration denotes

something of value exchanged by the contracting parties.4

In addition, for the smart contract to constitute a legally

binding contract for the sale of goods, the contract must

also satisfy the various requirements of Article 2 of the Uniform

Commercial Code (UCC), including its statute of frauds

requirements and its requirement that the contract set forth a

quantity in order to be enforceable.5 Practitioners will need to

evaluate on a case-by-case basis whether a smart contract meets

these elements and therefore represents a binding legal contract

for the sale of goods.

The Uniform Law Commission and the American Law Institute

established a Uniform Commercial Code and Emerging Technologies

Committee6 to study and evaluate the

UCC in the context of “among other issues, distributed ledger

technology, virtual currency, electronic notes and drafts, other

digital assets, payments, and bundled transactions,” and the

Uniform Law Commission released an issues memorandum7 discussing these topics in July

2021 following two years of committee meetings. While smart

contracts have been part of the discussion, no formal evaluation

for smart contracts has been performed by the Uniform Law

Commission or the American Law Institute, leaving open the

opportunity for clearer guardrails in the future as to whether a

smart contract amounts to a legal contract.

Smart Contracts vs. Smart Legal Contracts

Smart contracts are not to be confused with smart legal contracts. While a smart

contract is a computer program coded to effectuate an outcome upon

the occurrence of a triggering event, a smart legal contract is

“a legally binding agreement that is digital and able to

connect its terms and the performance of its obligations to

external sources of data and software systems.”8 The Accord Project makes clear that, although a

smart legal contract can use smart contracts via blockchain

technology, a smart legal contract can also be created using

traditional software systems without the use of blockchain.9

Vulnerabilities

While properly coded smart contracts could dramatically increase

efficiencies in supply chains, companies face a risk that their

smart contracts contain bugs or other technical issues such as data

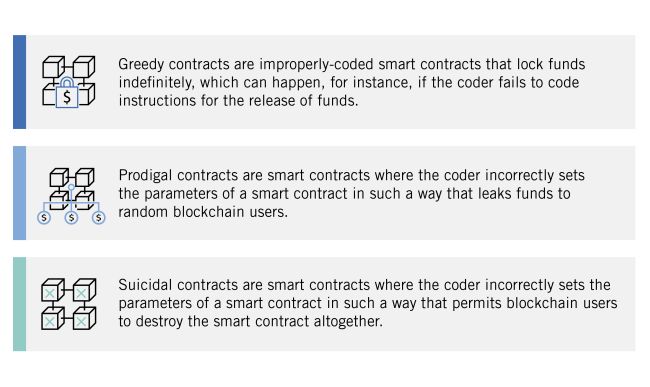

block corruption. There are three common types of vulnerabilities

that arise from improperly coded smart contracts: greedy contracts,

prodigal contracts, and suicidal contracts.10

In addition, another complicating factor for using smart

contracts is the inability of a non-coder to read whether the smart

contract actually does what he or she wants it to do. Even

though the parties may have a traditional text-based agreement in

place that provides the parameters for the smart contract, the

programmer could code the smart contract in a way that is not

consistent with the written agreement. If the businessperson

were unable to read code, he or she would have no way to verify

whether the coded smart contract matches the text-based

agreement.

Finally, because the immutable nature of blockchain also extends to

smart contracts (which live on a blockchain), once a programmer

codes and deploys a smart contract, immutability prohibits the

addition of any new functions to the smart contract.

Upgrading and otherwise altering smart contracts is an active area

of research in the blockchain community, and mechanisms for

altering smart contracts and best practices are still being

developed.

While smart contracts could increase efficiency in the supply

chain, real risks exist that the coder could set the smart contract

up improperly or that the smart contract fails to account for a

change in circumstances. Businesses seeking to employ smart

contracts will need to weigh the pros and cons carefully and

allocate the risks between the participants in the smart contract

accordingly.

Subscribe to the “Blockchain in Supply Chain”

Series

For a deeper dive into how supply chains could be transformed by

cutting-edge blockchain technology, we invite you to subscribe to

this “Blockchain in Supply Chain” series by

clicking here.

Footnotes

1. Levi, Stuart D. and Alex B. Lipton, An Introduction to Smart

Contracts and Their Potential and Inherent Limitations,

Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance,

2. See RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF CONTRACTS §

24 (AM. LAW INST. 1979)

3 .See RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF CONTRACTS §

22-23 (AM. LAW INST. 1979)

4. See RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF CONTRACTS §

71 (AM. LAW INST. 1979)

5. See Uniform Commercial Code §

2-201(1)

6. Uniform Commercial Code

and Emerging Technologies Committee, Uniform Law

Commission, (last retrieved September 7, 2021)

7. Uniform Commercial Code

and Emerging Technologies, Uniform Law Commission (July

9-15, 2021)

8. Frequently Asked

Questions, the Accord Project (last retrieved August 22,

2021)

9. Id.

10. Groschopf, Wolfram et al., Smart Contracts for

Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Conceptual Frameworks for

Supply Chain Maturity Evaluation and Smart Contract Sustainability

Assessment, Frontiers in Blockchain (April 9,

2021)

The content of this article is intended to provide a general

guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought

about your specific circumstances.

[ad_2]

Source link