[ad_1]

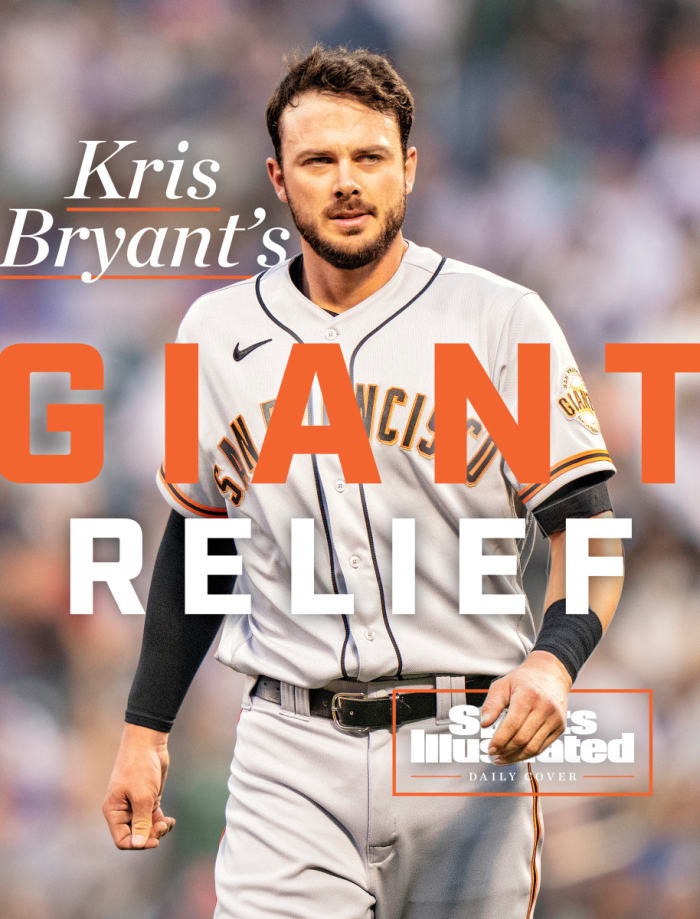

Kris Bryant glared at the clock. With 10 minutes to go before the July 30 trade deadline, he was still a Cub. He had spent three years answering questions about rumors that the team would deal him to save money—rumors, he notes, that ownership rarely had to address. He had battled anxiety about what a trade meant about him as a player. A free agent after the 2021 season, he had treated the first four months as a farewell tour, pausing an extra beat whenever the crowd at Wrigley roared his name. He and his wife, Jess, had taken a private visit to the Chicago team store so they could buy all the BRYANT 17 memorabilia they expected would soon be discontinued.

For so long he had wanted to be here. Now he wanted out.

The miraculous, curse-breaking 2016 World Series champions never became the juggernaut players and fans expected. They didn’t even make it to the Division Series after ’17. And this season was the worst of all. The Cubs had woken up on June 25 tied for first place. Then they lost the next 11 games. On July 29, they sent first baseman Anthony Rizzo—one of Bryant’s groomsmen—to the Yankees. Two hours before the 4 p.m. ET deadline, the Cubs traded closer Craig Kimbrel to the White Sox; an hour later, they sent shortstop Javy Báez to the Mets.

That left Bryant in the visitors’ dugout at Nationals Park, talking to Jess on the phone, counting the minutes. Is this really not going to happen? he thought.

“I got bitter,” he says.

A few seconds later, Jess would tell him that a friend scrolling Twitter had seen the news: He was headed to the Giants. He would rejoice, then burst into tears. He would watch as Rockies shortstop Trevor Story, the most obvious trade chip on the market, remained with his moribund team and pulled himself from the lineup in frustration. “Man, I feel for him,” Bryant says.

He would scramble to get to San Francisco from D.C., eventually flying home to Chicago and catching a plane the next morning. He would join the team with the best record in the sport. He would be in the Giants’ lineup for the National League Division Series against the rival Dodgers. He would find himself beaming nearly all the time.

But first he grappled with that bitterness. He tried to push the feeling aside. He has long endeavored to search for bright spots in dark moments. And there have been plenty of dark moments: The public sees him as a cerulean-eyed Express model and perennial All-Star who threw to first for the final out of the Cubs’ first World Series title in 108 years. He is also a 29-year-old father who has endured on-field struggles, a crisis of confidence and a devastating personal loss. So on July 30, he did what he has done for the last two years: He told himself that his suffering was not about him. It was about someone else.

Bryant received a standing ovation and a video tribute from the Cubs when he returned to Wrigley Field for the first time as a member of the Giants.

Kamil Krzaczynski/USA TODAY Sports

The Disney movie ended when the Cubs won the 2016 World Series. Bryant’s career did not. He had been named college player of the year in ’13, minor league player of the year in ’14, National League Rookie of the Year in ’15 and NL MVP in ’16. He had played six positions in his first two years in the major leagues, all of them well. So he showed up at spring training in ’17 facing perhaps a more challenging task than he expected.

“When you do some really cool things early on, you have to live up to those lofty expectations,” says Bryant. “When you’re so young, sometimes that’s hard to do.”

He made it look easy for a while. He was almost as good in 2017 as he’d been in ’16—a 142 OPS+ and 5.9 WAR, good enough for seventh in NL MVP voting—and after fighting left-shoulder inflammation for much of ’18, he was an All-Star in ’19.

Sign up to get the Five-Tool Newsletter in your inbox every day during the MLB playoffs.

Then came 2020 and the pandemic. Jess was eight months pregnant when the world came to a halt in March. The Bryants worried that she would have to give birth alone. (Kris was eventually allowed in, although no one else could join them.) Once Kyler was born in April, his parents worried constantly that they might catch the coronavirus and give it to the baby.

Meanwhile, Bryant had to be in shape whenever the season started, so he spent the COVID-19 suspension working out as if he were playing games. By the time the season started, he needed a break. He did not get one, physically or emotionally. League regulations strictly limited their interactions with other people, and he and Jess limited them further. For much of the season, when he left on road trips, her parents could not come help her with Kyler.

It all affected his performance. Bryant was hitting .182 when he broke his left wrist and tore two ligaments in his ring finger trying to make a diving catch in left field. He homered in his next at bat, but he eventually missed 15 games—a quarter of the season—as he recovered. The Cubs tried to protect him by limiting him almost entirely to third base, but that may have backfired.

Bryant initially came to his Swiss Army knife position by accident: Left fielder Kyle Schwarber tore his left ACL and LCL in the third game of the 2016 season, and the team had to reshuffle its roster to accommodate the loss. But Bryant has always liked the Little League mindset that bouncing around the diamond requires: Show up to the ballpark and find out what position you’re playing.

“It keeps you fresh,” he says. “I hope I can do this for the rest of my career. I really do think that I’m that type of player that can fill a hole when a guy needs a day off or fill a hole when a guy’s hurt. I take pride in that.”

Bryant threw to first for the final out of the 2016 World Series, the Cubs’ first title in 108 years. That season, he won the National League MVP award.

David E. Klutho/Sports Illustrated

He also craves the comfort his defensive versatility brings him when his offense is suffering. He can put less pressure on himself to hit when he knows he is helping the team in a variety of other ways.

Trapped at one position, he finished the 2020 season with a .644 OPS, the 28th-worst mark in the sport.

“You’d like to think that the game gets easier as you go along, but I find it gets easier in certain ways but much harder in other ways,” he says. “Just, you know, keeping that foot on the gas as you get older and continuing to have that same mindset: Failure is not really an option. I want to get better. And that’s kind of where I’m at.”

Even this season’s .866 OPS has come despite a .445 OPS in June, his worst full month ever. This only confirmed a deeply held fear: He is forever grousing that he has never been so bad at baseball before. Jess does everything she can to not roll her eyes. They had this exact conversation last year, and the year before that, and the year before that. She gently reminds him that he made it through his last crisis of confidence and he will make it through this one, too.

“You don’t know if [this is] the time where the struggles are really real and you just don’t have it anymore,” he says. “You go through a rut and you’re like, O.K., what can I fall back on? What experience have I had in the past to get me through this moment right now? You look back [at past struggles] and you’re like, I got through that moment. In the moment it felt like the end of the world, but now looking back on it, it’s like, I don’t even remember that moment! You’re still breathing; you’re still alive. You’ve just got to, you know, go through the storm.”

At times, those last months in Chicago felt like all storm. After his poor 2020 season, opposing executives speculated that the team might not even tender him a contract for ’21, his final season before free agency. He tried to ignore the conjecture. He had had plenty of practice: It has been rumored for years that Bryant’s Cubs tenure would end before his club control did. Chicago had manipulated his service time in ’15, costing him a year of free agency; he was not inclined to reward the team with a hometown discount. And the team was not inclined to make up the difference.

So early this season, the Bryants made that visit to the team store. They moved from downtown to Wrigleyville. Bryant traded basketball cards with his teammates and stayed at the ballpark an extra few minutes after both wins and losses. This would be one of the more challenging seasons of his life, but he wanted to enjoy it. He had survived worse.

For so long, Bryant never wanted to leave the Cubs. But his last months with Chicago made him realize that he wanted out.

Robert Beck/Sports Illustrated

A week before the Cubs reported for spring training in 2019, Jess and Kris crowded into an exam room near their Las Vegas home and waited to hear the sound of their child’s heartbeat. Instead they heard silence.

“You see the doctor do the ultrasound, and you look at their face, and you can see the life literally get sucked out of the room,” Kris says. “And then we’re stuck in there. It’s just a terrible, terrible feeling. We wanted it so bad.”

Jess was about eight weeks along. They had not felt a kick or learned the sex or chosen a name. None of that comforted them.

For a while, nothing did. Kris reported to camp and threw himself into baseball. Jess tried to find meaning in their loss. Her doctor had told her that one in three pregnancies suffer this fate. That got her thinking. A relative had experienced miscarriages, so she knew they were relatively frequent, but as she spoke with friends, she realized many other people felt they were alone.

“They were like, ‘I thought it was really uncommon. I’ve never talked about it,’ ” she says. “And I just remember reading a Bible scripture—I couldn’t tell you which one, but it was the concept basically, of, Sometimes you go through things, and it’s not for you; it’s for someone else. And I started thinking about that: Hey, I might have gone through this, but it wasn’t for me to be ashamed of or [wonder], why did this happen? I’m going to turn it into: Hey, someone else has been struggling with this. And you’re able to connect to someone on a different level.”

Suddenly she found her burden easier to bear. Kris marveled at her. “I’m so lucky to have my wife in my life,” he says. “It’s so easy, when you are struggling, to just curl up and not want to be a good human being. … She was so defeated, but for her to open up and share that she went through that, it helps a lot of people.”

He decided that if Jess could find beauty in one of the greatest losses of her life, he could do the same at work. When they had Kyler, Kris saw an opportunity. Kyler is 14 months old now, old enough to understand that his dad plays baseball, although not quite old enough to understand that other people do, too. (The Cubs played the Dodgers in Los Angeles on Cody Bellinger bobblehead night; Kyler often kisses the toy and says, “Daddy!”) He has not struggled much yet. But he will. And it is of those moments that Bryant thinks whenever he plays poorly.

“When I come home and just look him in the face, it’s like, Man, I’m gonna have so much advice and wisdom for him when he’s older,” Bryant says. “Not just in sports, but just in life.”

Bryant is rejuvenated now that he’s playing with the Giants. Their clubhouse reminds him of that of the 2016 Cubs.

Brad Mangin/Sports Illustrated

Some day, Kyler might have a first day of school that goes something like his dad’s first day with the Giants: trying to quiet the butterflies in his stomach as Jess frets over whether he will make friends. The baseball world is small enough that everyone has a connection with someone on every team, but the Bryants knew no one in San Francisco. So they were relieved when a half dozen players texted Kris to welcome him.

Those first hours unfolded in a whirlwind. A few Giants wives connected Jess with a realtor. Within two days, they were in a furnished house. Meanwhile, Kris was meeting with Giants officials. In his early conversations with president of baseball operations Farhan Zaidi and manager Gabe Kapler, he pressed them to let him keep moving around the diamond. “You always love to hear that,” says Zaidi. Bryant has played third base and all three outfield positions for San Francisco.

He also made peace with the trade. Jess had spent several years trying to convince him that all the rumors didn’t necessarily mean that the Cubs didn’t want him—they meant that someone else really did. She had not always succeeded. But now he was here, familiarizing himself with a new field surface, new teammates, new drills. The clubhouse reminded him of that of the 2016 Cubs. He found himself rejuvenated.

He hit a go-ahead home run in his second at bat as a Giant, but it was his first at bat that remains his favorite moment of his time there so far. A standing ovation greeted him as he strode to the plate … and nearly the same reaction followed him as he trudged back to the dugout after striking out.

“I think, for [the front office], the sort of reception that he’s gotten in San Francisco was maybe a little bit of a blind spot we had,” says Zaidi. “I mean, we know what a good player he is, but we maybe didn’t have a full appreciation of what a big deal he would be to the city.”

Bryant is a free agent after this season, but he’s in no rush to leave San Francisco.

Brad Mangin/Sports Illustrated

Zaidi learned that the fans saw Bryant as a star. Bryant learned that they appreciated his eight-pitch at bat. He has enjoyed the team’s focus, too, on process over results.

“I just think I’m happier,” he says. “It’s not like I wasn’t happy in Chicago, but it’s new. It’s fun to be a part of something new, and of course, the team is winning. It feels good.”

Fans have been talking about when Bryant would be a free agent since before he even played a major league game. Now here he is, weeks from that payday, and he is in no rush to get there.

More MLB Coverage:

• Lance McCullers Jr. Is Emerging as a True Playoff Ace

• Dodgers Avoid Potential Pitfall to Give the People What They Want

• The Yankees Are Simply a Step Behind

• Welcome to the Updated Version of Playoff Baseball

[ad_2]

Source link