[ad_1]

Ground teams are stepping through testing of three small CubeSats launched with the Landsat 9 remote sensing satellite last month, preparing the small spacecraft for exoplanet observations and communications experiments. NASA says engineers have not established contact with another CubeSat designed for space weather research.

Four CubeSats launched as rideshare payloads with the Landsat 9 mission Sept. 27 aboard a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket. The Atlas 5 successfully deployed the Landsat 9 satellite, a joint project between NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey, into a 420-mile-high (675-kilometer) polar orbit after liftoff from Vandenberg Space Force Base, California.

The Atlas 5’s Centaur upper stage maneuvered to a lower altitude to release four CubeSats carried inside dispensers on a secondary payload adapter.

The small secondary payloads — two for NASA and two sponsored by the U.S. military’s Defense Innovation Unit — ejected from carrier modules on the Centaur stage, according to ULA.

One of the CubeSats, named CuPID, was built to study the interactions between solar activity and Earth’s magnetic field, probing dynamics that impact space weather. The Cusp Plasma Imaging Detector, or CuPID, carries instruments to measure X-rays emitted when plasma from the solar wind collides with neutral atoms in the Earth’s atmosphere.

Denise Hill, a NASA spokesperson, said Thursday that ground teams were still attempting to establish contact with CuPID. Those attempts are taking longer than expected, Hill said, but officials aren’t giving up. They continue to try to acquire signals from the CubeSat.

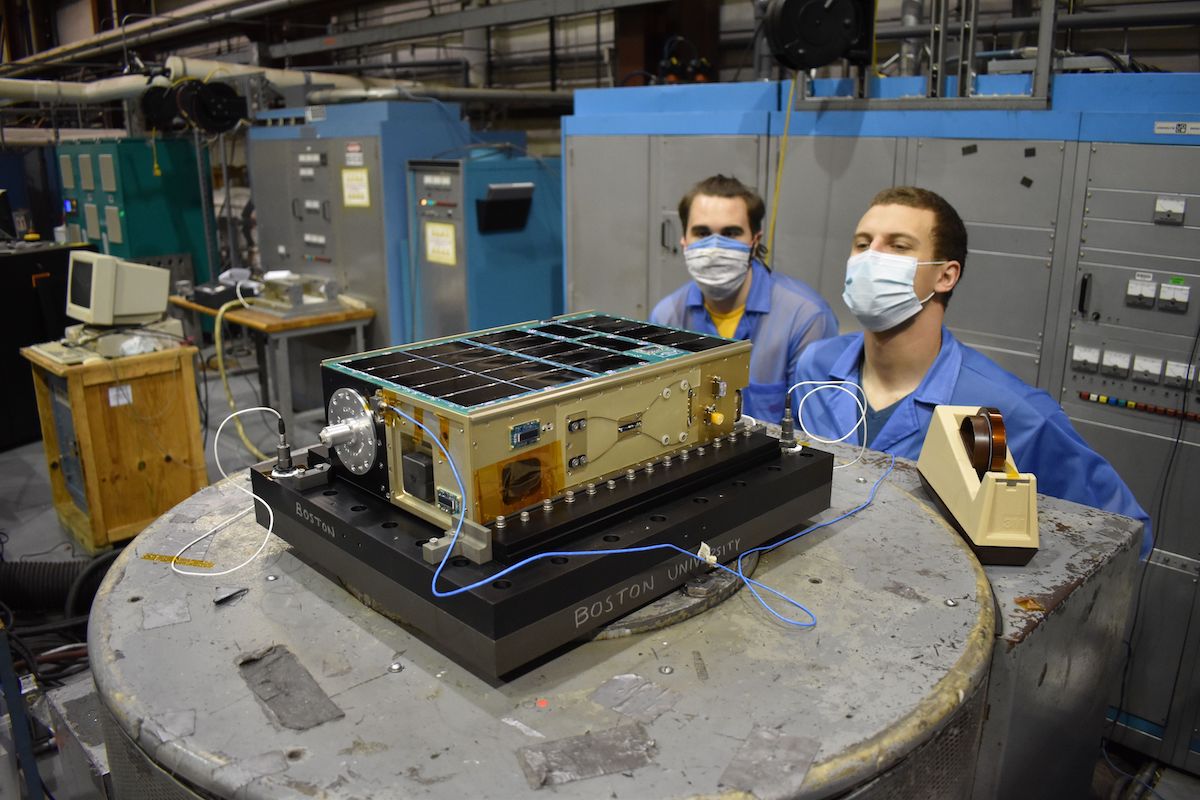

CuPID, based on a 6U CubeSat platform, was developed by students and researchers at Boston University. Team members there did not respond to multiple requests for updates about the small satellite.

The spacecraft is about the size of a toaster oven, and hosts the first wide field-of-view soft X-ray camera to fly in orbit. Data from CuPID was meant to complement research from larger NASA missions, such as the Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission, observing how Earth’s magnetosphere responds to inputs from the sun.

The interactions between solar activity and Earth’s magnetosphere drive space weather, which can disrupt communications, electrical grids, and satellite operations.

Another NASA-supported CubeSAT, known as CUTE, carries a tiny telescope to look at atmospheres on planets outside our solar system. Officials wrote on the mission’s website that ground teams successfully established a communications link with the CUTE spacecraft after launch.

The Colorado Ultraviolet Transit Experiment is funded by NASA’s astrophysics division. The small spacecraft will observe transits of giant planets in front other host stars. These planets, called “hot Jupiters,” orbit close to their stars, where their atmospheres become superheated, potentially allowing the gas molecules to escape into space, according to NASA.

CUTE will watch at least 10 of the giant planets cross in front of their stars, observing five to 10 transits per planet in about seven months, NASA said.

The satellite will measure how ultraviolet light from the star changes as it passes through the planet’s atmosphere.

“Key elements in the planet’s atmosphere, such as magnesium and iron, absorb near-ultraviolet light, providing clear evidence of their presence,” NASA said in a press release. “By taking repeated measurements of these atmospheric elements for the same planets, CUTE will help us understand how quickly those planets are losing their atmospheres, and how that changes over time.”

CUTE “is looking at an important process we think also matters here in the solar system, namely the loss of an atmosphere,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, head of NASA’s science mission directorate. “Remember, Mars used to have a much thicker atmosphere around the planet.”

Results from missions like CUTE could help scientists understand planetary evolution, particularly how planets maintain conditions that can support life.

The two military-sponsored CubeSats launched alongside Landsat 9 were developed by an Austin, Texas, based company called CesiumAstro to test advanced communication technologies.

The two small satellites are part of Cesium Mission 1, developed in partnership with the Defense Innovation Unit, part of the U.S. Defense Department. CesiumAstro said in a press release that engineers plan a month of checkouts on both spacecraft before commencing the experimental phase of the mission.

The satellites cary active phased array communications systems and intesatellite links. The U.S. Space Force said the mission will demonstrate dynamic waveform switching and dynamic link optimization capabilities.

“CM1 provides an on-orbit platform that consists of two satellites for customer experiments that push the boundaries of small satellite communication,” CesiumAstro says on its website.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.

[ad_2]

Source link