[ad_1]

Amid lush mountains, fed by wealthy rivers, there was as soon as a area of nice prosperity, and relative peace. Then got here invaders from elsewhere who wished the area’s riches. Bit by bit, then chunk by chunk, they claimed them. They have been heroes in their very own story. So, for a time, they grew to become heroes on this one too. And who doesn’t need to be a hero?

The foreigners finally left. They’d suffered crushing defeats and agreed it was time. But, as their ships drew away, the area they left wasn’t the area it had been. That is the story of colonialism all over the world. And it’s the story of how India, together with valuable metals and supplies, misplaced a lot of its tales.

The tales, although 1000’s of years previous, had lived on of their folks. Most had by no means been written down. They’d been painted; carved into stone and wooden; however a narrative should be informed, with a view to survive. Without the retelling, it fades. Over centuries, once-rich tales light, in all corners of the land. And so it was that when the area discovered prosperity once more, the folks regarded round in confusion. They had new metals and supplies. But they knew there had been extra.

This is how Sharat Prabhath would possibly inform the story of India’s lacking tales. It’s how his grandfather and great-grandfather might need. He comes from an historical line of storytellers. Now, he’s telling tales once more.

His tales are populated with gods and goddesses, heroes, legendary creatures and magical worlds, but in addition superstar unhealthy boys and present affairs. He performs his harikatha (a type of conventional discourse largely seen in peninsular India) in his mom tongue of Kannada, in addition to in English and Hindi. As his ancestors did, he makes use of track and dance, humour, satire, even on a regular basis occasions, to maintain the narrative alive.

“For a long time, our traditional arts and crafts were looked down upon. Our practices were called primitive,” says Prabhath, 32. But our tales matter, he provides, as a result of “time and space are abstract; stories add meaning to them.”

In a world that has returned to storytelling as a method of enhancing communication abilities and confidence, self-expression and schooling., brand-building even , Indian oral storytellers are venturing into hitherto unexplored areas. They’re utilizing the codecs and legends of their roots, however adapting these for the twenty first century, including up to date twists and views; they’re merging storytelling and science; they’re utilizing tales for group remedy; and so they’re uncovering legends largely forgotten which have lived on in artwork and structure.

In Bengaluru, Aparna Jaishankar, 44, is drawing on historical work, temple artwork and tutorial analysis to supply new views on tales from the Mahabharata. The ticketed occasions she helms draw folks aged 19 to 90.

In Chennai, Deepa Kiran, 45, presently pursuing a PhD in storytelling and language, is making an attempt to bridge the hole between the sciences and humanities utilizing storytelling gadgets (rocks that discuss; tales in regards to the historical past of the sciences in India).

“In our oral storytelling traditions, it was adults who would listen to the stories. In the same vein, we would like to bring adults into the world of stories,” says Meghana Bommatanahalli, 47, of the Hyderabad Storytellers Association, which holds story circles by which contributors swap tales round a predetermined theme.

And amid the trauma of the pandemic, in 2020, 5 storytellers arrange the Indian Storytellers Healing Network (ISHN), to advertise the sharing of tales as a method of therapeutic. The periods are nonetheless held on-line, the core group of 5 storytellers themselves scattered throughout the nation. An ISHN storyteller begins with a story, then these within the viewers share their reflections and accounts. “The telling of one’s own story lightens a load,” says ISHN member Sowmya Srinivasan, a psychologist. “Listening to another’s tale promotes empathy and compassion. Stories are how people feel less alone.”

Take a glance, then, at a few of India’s up to date oral storytellers, the traditions they’re carrying ahead, and the brand new ones they’re crafting.

Curses, consent and Kolkata biryani

Aparna Jaishankar is dedicated to rendering the invisible seen once more. So, in her storytelling, she spotlights uncommon tales hidden in acquainted locations: tales of consent and historical anti-caste warriors within the epics, folks tales tucked away atop well-known temples, and culinary secrets and techniques from a number of hundred years in the past that at the moment are forgotten.

Reveal these tales and so they breathe once more and evolve, says Aparna, 44. She likes to inform of the time she narrated a story from the Mahabharata to a gaggle of youngsters in Bengaluru. In the story, Arjuna resists the advances of Urvashi, probably the most lovely of the apsaras; enraged, she responds by placing a curse on him.

The youngsters noticed this as a narrative not about energy and need, Aparna says, however about consent. “It opened up conversations about consent for both genders. They were discussing how it is important to learn to handle surges of desire.”

Aparna has been knowledgeable storyteller since 2015, with a particular concentrate on the Mahabharata. For audiences beneath the age of 10, she retains to the acquainted tales. For youngsters, she picks tales the place there may be dilemma and room for interpretation.

It’s when she’s telling the tales for older audiences that it will get most attention-grabbing. Aparna has been holding month-to-month ticketed reveals for grownup audiences since 2016, and right here she discusses, for example, how Duryodhana — the oldest of the Kauravas and the villain of the Mahabharata — continues to be worshipped in components of Kerala and Uttarakhand as somebody who sought to abolish caste.

Two temples to Duryodhana nonetheless stand, one in every of the states. “In the temple in Kollam, Kerala, the origin story is that certain castes were not allowed to share food with the rest of the community, and Duryodhana abolished this practice,” Aparna says. “In Osla, Uttarakhand, it is said that the people loved Duryodhana so much that after he died in the Great War, a river was born of their tears.”

Meanwhile, in Odisha, there’s an alternate tackle how Krishna first revealed himself to Arjuna. “Traditionally, it is believed that when Arjuna hesitates amid the Great War, Krishna motivates him by giving him the Geetopadesh. That’s supposed to be the first time Krishna reveals himself as a form of Vishnu,” Aparna says.

But within the Odia Mahabharata, that’s not the primary time in any respect. The first time is earlier than the Great War, when Arjuna goes on a pilgrimage alone, to mirror upon the futility of battle. Krishna reveals himself as a creature made up of components of 9 completely different animals, every with its personal significance. “Finally appearing to Arjuna as a whole, he says, ‘You are too small to see the whole picture, and so you must react based on what he is shown’.” The story, known as that story of the Nabagunjara, is exclusive to this area, and is depicted in Patachitra artwork and within the Neela Chakra or metallic wheel atop the Jagannath Puri temple.

Apart from tales of the Mahabharata, Aparna is now working to convey extra storytelling into colleges, notably historical past courses. Before the pandemic, she held weekend periods at libraries in Bengaluru, about Indian empires such because the Cholas and Rashtrakutas.

“What we learn in our textbooks is only a small section of history that is presented quite boringly,” Aparna says. “Take the Kolkata biryani and why it contains potato, for example. Dig in and you’ll find that it has something to do with the Doctrine of Lapse.”

Kings, demons, Socrates and Mark Twain

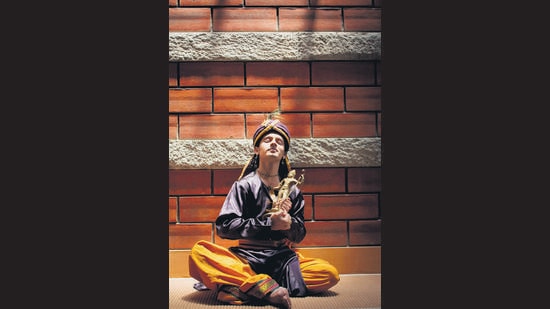

Sharat Prabhath, 32, is the great-grandson of Venkanna Dasa, one of many nice haridasas. These have been conventional storytellers who carried out in what at the moment are Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Telangana and Maharashtra.

Their artwork type, harikatha, concerned singing, dancing and philosophising, typically with a little bit of humour thrown in. They sometimes enacted tales of kings and demons, myths and epics. “But I have also heard that my great-grandfather performed a harikatha on Swami Vivekananda,” Prabhath says. “This was in the early 1900s. This gives us an idea of how open people were even back then.”

Prabhath is now making an attempt to contemporise harikatha, whereas ensuring it’s genuine and retains its essence . He’s been performing since he was 19, however that was already 2009, so “I have never watched a harikatha performance in the way it was performed back in the day,” Prabhath says. “The style I have incorporated is based on descriptions from my father, teachers and scholars, and my own additions. I still feel like a newborn every time I go on stage.”

Prabhath performs in Kannada, English and Hindi, and is brushing up on his Sanskrit. He attracts from the devotional music of Purandara Dasa and historical poetry in Marathi and Tamil, but in addition writes his personal songs. Between songs, he breaks into extempore oration. Here, he would possibly quote Socrates or Mark Twain; discuss on a regular basis struggles resembling discovering time to go to the fitness center; focus on Elon Musk, the battle in Ukraine, terrorism and the decline of communism.

This helps maintain the viewers’s consideration by a standard efficiency, he says, serving a operate that has long-existed on this custom: that of the upakatha or subplot. “It is traditional to deviate to unconnected stories, just to jolt people out of their reverie.”

Sometimes, Prabhath simply borrows a joke. A favorite is the one by which Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson go tenting. Holmes asks Watson what he sees within the evening sky above them. The good physician replies with an elaborate tackle astrology, theology and Man’s place within the universe. “What does it say to you, Holmes?” he lastly asks.

“Watson, you idiot,” Holmes replies. “What it tells me is that someone has stolen our tent!”

Rocks that discuss, numbers that dance

Deepa Kiran is many issues: a single mom to 2 boys, a Bharatanatyam dancer, a diet and dietetics graduate, a glider pilot, a coder. In her years as a pupil, she says, she was invariably been disenchanted by her science textbooks.

In 2007, whereas finding out for an MPhil, she explored the language of science communication. A key downside, in fact, was that the scientific and inventive communities weren’t collaborating. In her position as a storyteller, Kiran goals to bridge this hole.

For occasion, she tells tales to kids about stones and rocks. These vary from the mythological origin tales for formations such because the Rama Setu to the science of how the Deccan Plateau was born. “The aim is to offer relevant stories that serve to create a curiosity and emotional connect. And to interestingly present information,” says Kiran, 45.

In her interactive, musical storytelling periods, viewers members get to suppose, guess at solutions, sing and dance alongside. How does her younger viewers reply? “There are always spontaneous conversations,” Kiran says. There are extra lingering impacts too. “One parent of a four-year-old said he hadn’t ever gone near rocks before. But the Monday after the storytelling session, he apparently ran to the rocks in his school grounds and began telling his classmates about how rocks are our friends and we have to take care of them.”

Following one other of her passions — tales of science from Indian historical past — Kiran has performed storytelling periods for the Birdwatching Association of Andhra Pradesh and the Indian Science Congress, in 2021. “I told stories on zinc extraction (India was one of the very few countries that knew how to do this), on chess and humbling a king, and I introduced math in a story through dance, as numbers can be converted into a jathi (rhythmic pattern).”

Kiran is presently pursuing a PhD in storytelling and language from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT)-Madras. “We don’t have too many students from literature and the humanities here. So the other interesting upside is I am trying to connect with students from science, math, technology, metallurgy and other fields, who are interested in creative education,” she says.

She can also be engaged on a collection of tales about India, which she shares by way of Instagram (@over2deepakiran) and YouTube (Deepa Kiran). She’s taken a break for exams, however “I have an unending number of stories and would love to go on,” she says.

A billion untold tales

The many hues of affection; letters (written, learn or heard of); espresso memoirs: these are among the themes which have been picked for month-to-month story-swap periods on the Hyderabad Storytellers Association (HYSTA). The periods have been launched in February, in English, Telugu and Hindi (Urdu swap meets are within the works).

“We are all stories, some told, many untold,” says Krishna Chaitanya, 42, a storyteller and HYSTA member. “It is our mission to build a conversation around stories as a medium of expression and support. Here, stories are told and listened to in a non-judgmental, nurturing space, followed by a sharing of individual takeaways that accentuate how the stories connected with each one’s experiences.”

HYSTA was based in 2019. “Storytelling for adults has such a rich history in India, but it’s one that is being fast forgotten. In storytelling traditions such as the burrakatha and oggukatha, it was adults who would listen. We want to revive that,” says founding member Meghana Bommatanahalli, 47.

The group is made up of storytellers from completely different professions: enterprise analysts, former software program engineers, content material writers, lecturers, dancers, singers, psychologists, parenting coaches, practitioners of neuro-linguistic programming.

On common, periods draw 50 to 70 folks. HYSTA additionally collaborates with libraries, artwork galleries and colleges to conduct periods for kids. And there are plans for a pageant to advertise conventional storytelling varieties with a recent twist as a approach of bridging the hole between historical oral narratives and the trendy world.

Meanwhile, the swap periods are producing all-new tales. In the session themed The Many Hues of Love, one participant narrated a story a couple of Valentine’s Day she spent together with her hero, her father. Another spun a yarn of elusive conferences and a tragic parting between two loopy lovers… who turned out to be automobiles.

How the sunshine will get in

Jyoti Pande sees tales as greater than an important artwork type; she believes they will heal.

“They have the power to bypass the conscious mind, since there are no defences in play when a person is listening to a story. Stories work at a deeper level than casual conversation,” says Pande, a psychologist and member of the Indian Storytellers Healing Network (ISHN).

ISHN was based in 2020 by 5 storytellers based mostly in Bhopal, Mumbai, Bengaluru and Coimbatore. Amid the pandemic, the purpose was to make use of tales to advertise self-exploration, restoration and therapeutic. The periods are nonetheless held on-line.

The organisation conducts month-to-month story circles round themes that vary from shakti or internal energy to the concept “there is a crack in everything; that’s how the light gets in”. In every session, the moderator tells a narrative, after which there are actions resembling role-play, drawing, self-reflection and dialogue.

ISHN storytellers supply their tales from present ones and their very own life experiences. ISHN member Ramya Iyer, for example, appears for tales that transfer her. One of her favourites is an African folktale referred to as the Secret Heart of the Tree, by which a younger hare is out on an journey and rests within the shade of an previous baobab tree.

“He sits under the tree, and he takes deep breaths,” says Iyer. “While I’m telling the story I take those breaths. And there are others who would feel the need to take them too.” The hare communes with the previous tree and is rewarded with a stroll into the tree’s secret coronary heart, and the present of a gold ring. Later a hyena tries to do the identical, however he’s not as sort because the light hare and will get caught inside the key coronary heart of the tree.

Iyer has added a second chapter to the story. “I bring in the hare’s son, who goes looking for the tree many years later, and is gifted with a journey into the secret heart. The young hare guides the hyena back out into the world. The touching forgiveness, a call to nestle and rest are some reflections that have left me very moved.”

Often, after a narrative is informed, folks focus on what they took away as its most salient message, and share tales from their lives alongside that theme. “A healing circle allows participants to become vulnerable, authentic and expressive,” says Geetanjali Kaul, a member of ISHN.

Sowmya Srinivasan, a psychologist and likewise a member, recollects sharing a narrative about how hooked up she was to her bicycle, which she left behind when she acquired married. “It left a void within me,” she says. “In order to fill that gap, many years later, I went on a cycling expedition in the Western Ghats. This triggered a lot of sharing from participants around what they had to leave behind or let go of and some poignant stories emerged.”

Personal tales work like magic potions, provides Poonam Joshy, the group’s fifth member. “I often tell stories from my life because I feel we tend to ignore our own stories. We never see their worth. But personal stories bring out many stories from listeners and suddenly they start seeing their own story with pride.”

Enjoy limitless digital entry with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to proceed studying

[adinserter block=”4″]

[ad_2]

Source link