[ad_1]

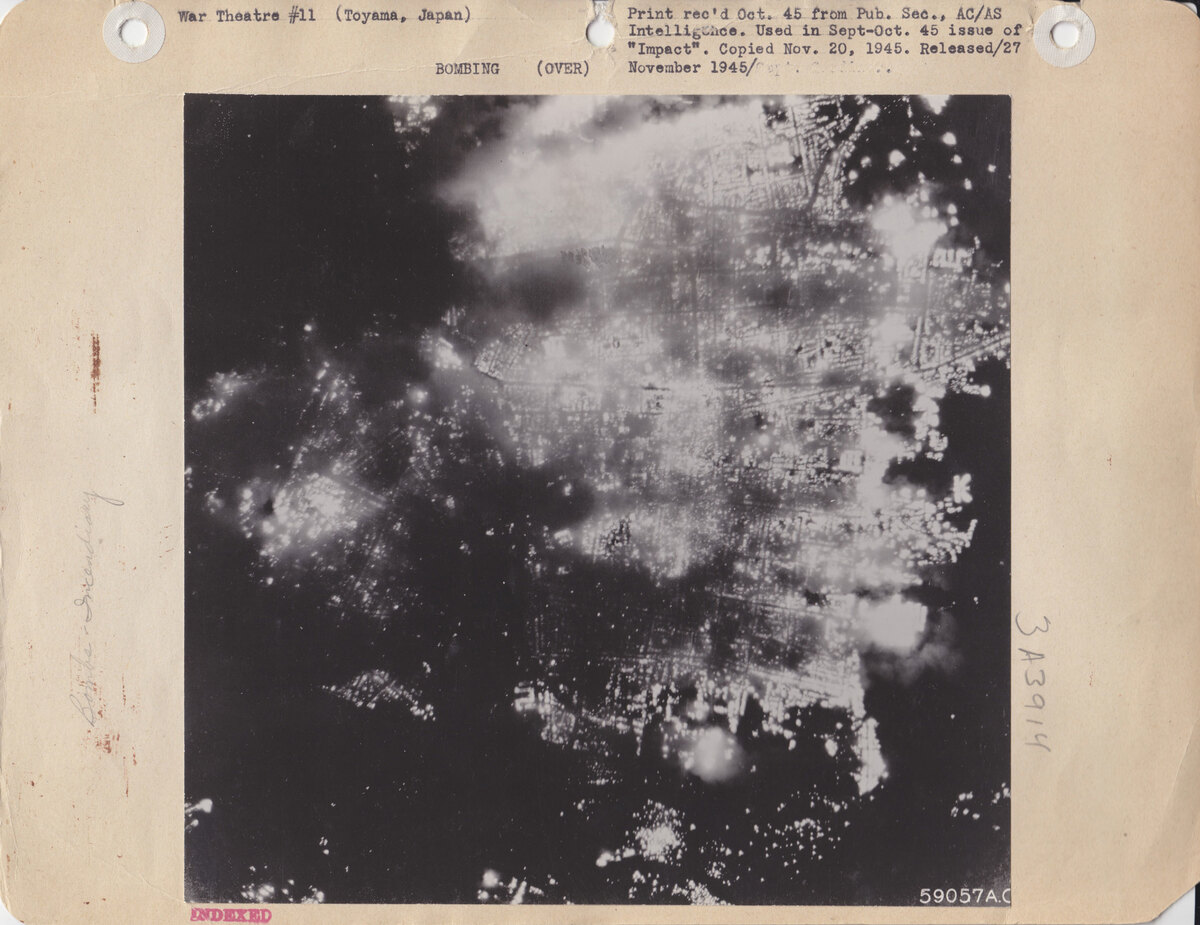

A photograph showing Toyama, Japan, aflame after the U.S. attack on Aug. 1, 1945. Most of the city’s population was left homeless.

U.S. Army Air Forces

hide caption

toggle caption

U.S. Army Air Forces

A photograph showing Toyama, Japan, aflame after the U.S. attack on Aug. 1, 1945. Most of the city’s population was left homeless.

U.S. Army Air Forces

Cary Karacas (@CaryKaracas) is associate professor of geography at the City University of New York – College of Staten Island and the Graduate Center. David Fedman (@dfedman) is assistant professor of history at the University of California, Irvine. Together, they maintain JapanAirRaids.org, a bilingual digital archive.

On Aug. 1, 1945, 12-year-old Hideko Sudo went to bed fully clothed and full of worry. For days, air raid alerts had left the coastal city of Toyama on edge, prompting her school’s closure. More alarmingly, earlier that day, American planes had rained down leaflets warning of an imminent attack.

Hideko’s fears proved well-founded. Despite a sophisticated alert system and a decade of air defense drills, the arrival just after midnight of a wave of B-29 bombers plunged Toyama into chaos. Superfortresses — 173 of them — encountered only sparse antiaircraft fire as they released around 1,500 tons of incendiaries onto the city’s center.

In a few short hours, Toyama was enveloped by a “sea of fire,” Hideko recalled in a written account. Over 95% of the city was incinerated, leaving around 2,600 people dead. While Hideko’s family survived, they numbered among the 165,000 left homeless, virtually the entire population.

With the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings upon us, we would do well to retrieve the burning of Toyama from the margins of public memory. For too long, scholarly predilections and public fascination with the atomic bomb have divorced the mushroom clouds from the firestorms that preceded them.

Rather than a sideshow to the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on Aug. 6 and Aug. 9, the incendiary destruction of cities was a fundamental facet of the war against Japan. The atomic bombings evolved out of a fierce U.S. campaign to target and destroy entire cities, in hopes of forcing a Japanese surrender.

This was not how air power strategists had initially imagined the war against Japan. The commitment at first was to the precision bombing of “war-making targets,” such as airplane factories.

Planes, however, struggled to hit their targets, due in no small part to the jet streams they encountered while flying at high altitudes over Japan. Eager to both justify the immense costs of the newly developed B-29 and play a central role in the defeat of Japan, U.S. Army Air Forces officials in Washington, D.C., were hungry for results.

Enter Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay, the commander of the 21st Bomber Command based on the Mariana Islands, who, in early 1945, ushered in a shift to nighttime incendiary area bombing — a doctrine that quickly moved to the center of the American air assault against Japan.

An aerial view of Tokyo shows destruction after American bombardment in 1945.

Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

An aerial view of Tokyo shows destruction after American bombardment in 1945.

Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

The scale of destruction wrought by this scorched-earth campaign remains underappreciated. By the time of the assault on Toyama, incendiary raids had already destroyed significant portions of dozens of cities and wiped out over a quarter of Japan’s housing.

Some Americans may be familiar with the firebombing of Tokyo on March 10, 1945, the most destructive incendiary air raid in history. Overnight, B-29s burned down 16 square miles of the capital’s main working-class neighborhood, claiming an estimated 100,000 lives.

Elated with the results, LeMay thereafter sent squadrons to burn down Osaka, Nagoya and other large cities in quick succession. In just 10 days, the U.S. Army Air Forces reduced 32 square miles of urban fabric to ashes.

Further bombing of these major metropolises in April and May resulted in destruction that one staff officer described as “beyond our wildest hopes.”

In what remains one of the most striking gaps in American public memory regarding the war with Japan, the AAF thereafter turned its sights on cities such as Toyama that were of minor or negligible importance to Japan’s war machine. Between June 17 and Aug. 14, one after another of Japan’s smaller cities joined their larger cousins in fire and ruin.

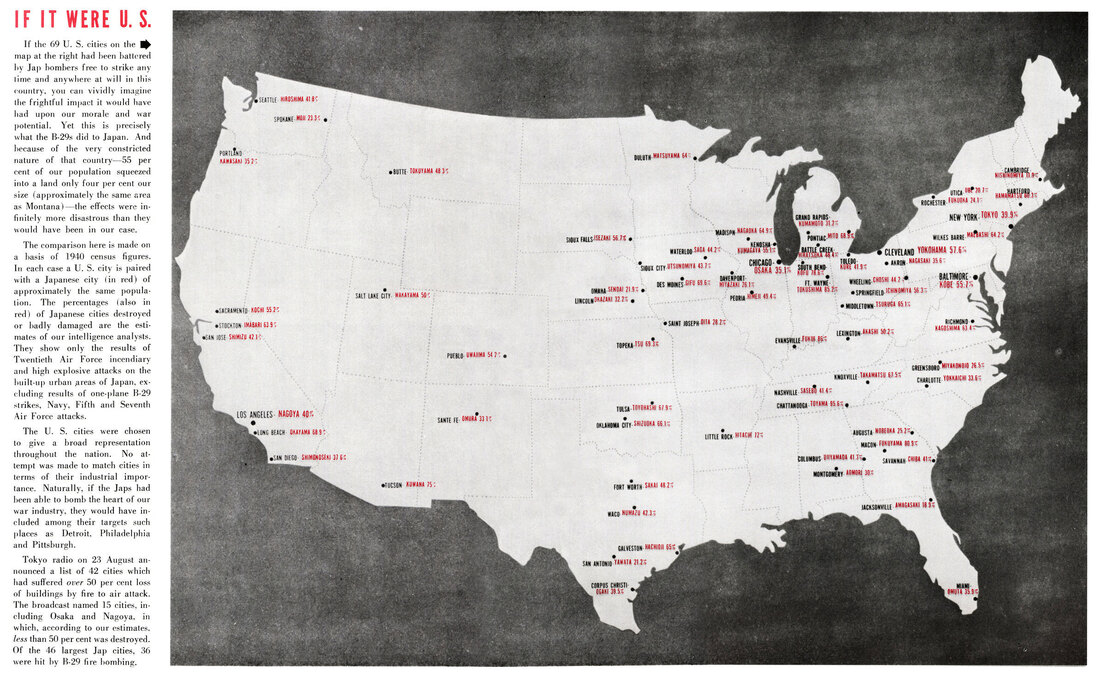

A U.S. map from Impact, a wartime government magazine produced for the Army Air Forces, highlights the extent of destruction to Japanese cities by showing dozens of American cities with comparable populations.

Impact via Curtis LeMay Papers/Library of Congress

hide caption

toggle caption

Impact via Curtis LeMay Papers/Library of Congress

A U.S. map from Impact, a wartime government magazine produced for the Army Air Forces, highlights the extent of destruction to Japanese cities by showing dozens of American cities with comparable populations.

Impact via Curtis LeMay Papers/Library of Congress

In total, 8,000 sorties dropped roughly 54,000 tons of incendiary bombs on 66 cities, killing (by conservative estimates) about 180,000 people. The attacks burned 76 square miles of urban Japan to the ground.

To bring home the extent of the destruction, one postwar report by a government magazine included a U.S. map showing dozens of American cities with comparable populations, asking the reader to imagine (as in the case of Toyama) the incineration of 96.5% of Chattanooga, Tenn.

Still, there were sensitivities to potential criticism from the American public, so AAF officials commonly used sanitizing language to mask the fact that they were targeting entire cities for destruction. Press releases described attacks not on cities, but on “industrial urban areas.” Tactical reports set their sights not on densely populated neighborhoods, but on “worker housing.”

In the privacy of briefing rooms, AAF officials made no bones about the fact that they were targeting residential areas and civilian populations. Publicly, however, they went to great pains to cast Japanese cities as singularly military or industrial in composition.

Toyama is a case in point. Although planners highlighted the city’s industrial sites, maps distributed to flight crews led directly to the residential city center. By dawn, Toyama’s schools, shrines, hospitals, and neighborhoods lay in ruins. Left unscathed were the war-related factories just outside the city.

Carl Spaatz, the commanding general of the newly christened U.S. Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific, handwrote an amendment to a press communique on the bombings of Toyama and three other small cities to emphasize that bombers struck “industrial areas” rather than the entirety of each city.

While the scale of Toyama’s destruction was extraordinary, the planning and prosecution of this raid was business as usual. In the parlance of American flight crews, the firebombing of this city was just another “milk run” — an act by then so commonplace it was akin to a local neighborhood delivery.

With major newspapers and magazines regularly running stories detailing such urban destruction, the American public on the eve of the atomic bombings had come to see the burning of Japan’s cities as part and parcel of the war.

If this firebombing campaign shaped public perceptions of what constituted an acceptable target, it also played a part in bringing the war to an end. While historians have rightly emphasized the atomic bombings and the Soviet Union’s declaration of war against Japan as decisive inflection points, we should not forget that incendiary raids continued until the penultimate day of the war.

The Japanese state had utterly failed to protect its urban population. As the number of homeless ballooned into the millions, officials feared widespread domestic unrest. A multitude of interlocking factors figured into the calculus of Japan’s surrender, and the cumulative effects of these incendiary raids were among them.

This August, remembering the incineration of Toyama and other smaller Japanese cities allows us to arrive at a fuller understanding not only of the course of the Pacific War, but also the evolution of American air power at the dawn of the nuclear age.

We also find a reminder of the ease with which proclamations of the intent to protect civilians during war can mutate into an embrace of attacking the cities in which they reside.

Barely five years after the surrender of Japan — during the Korean War — the U.S. once more abandoned its stated commitment to refrain from attacking civilians, designating North Korean cities and towns as “main bombing targets.”

As the world pauses this month to reflect on the past, present and future of nuclear weapons, we might also take a moment to think more critically about how cities are rendered into targets.

[ad_2]

Source link