[ad_1]

Clockwise from prime left: lawyer Liudmyla Lysenko in Kyiv; restaurant co-owner Iryna Savchenko in Kramatorsk; tour information Artem Vasyuta in Odesa; homemaker Nataliya Kucherenko within the Sumy area; obstetrician Iryna Kulbach in Dnipro; and architect Max Rozenfeld in Kharkiv.

Claire Harbage/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

Clockwise from prime left: lawyer Liudmyla Lysenko in Kyiv; restaurant co-owner Iryna Savchenko in Kramatorsk; tour information Artem Vasyuta in Odesa; homemaker Nataliya Kucherenko within the Sumy area; obstetrician Iryna Kulbach in Dnipro; and architect Max Rozenfeld in Kharkiv.

Claire Harbage/NPR

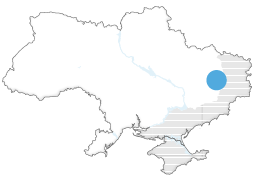

CITIES ACROSS UKRAINE — Russia’s army assault on Ukraine started a decade in the past, when it occupied the southern peninsula of Crimea. A bloody invasion of japanese Ukraine, which concerned active-duty Russian troops, the West says, adopted.

Two years in the past, that localized battle gave solution to a full-scale invasion by Russia’s armed forces that has shaken each nook of Ukraine.

On this grim anniversary, NPR visited folks in six Ukrainian cities who’ve tailored, every in their very own manner, to struggle — and maintained a way of hope.

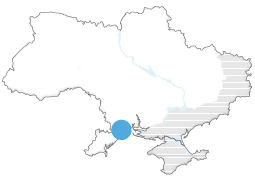

Odesa

A historic map of town is seen on a wall in Odesa.

Claire Harbage/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

A historic map of town is seen on a wall in Odesa.

Claire Harbage/NPR

Artem Vasyuta gives excursions of his legendary hometown even throughout struggle.

“My official title is tour guide, but I do this job because I want to tell Odesa’s story,” he says, pausing. “A story that includes Ukrainians.”

Located on Ukraine’s southern coast, Odesa is named the Pearl of the Black Sea. Its port was once a heady, multicultural crossroad the place the dominant language was Russian. But Russia’s full-scale struggle on Ukraine all however shut down the port and its exports. And two years later, Odesa has misplaced all sentimentality for something associated to Russia.

In December 2022, locals took down an unlimited statue of Catherine the Great, the Russian empress credited (unfairly, many Ukrainians say) as town’s founder. Vasyuta factors to the empty base the place the statue as soon as stood and says he isn’t sorry.

“Russians are trying to erase us as a country,” he says. “I don’t see why we shouldn’t erase their imperial monuments.” And, he provides, “So much of Odesa is viewed through a Russian-Soviet lens. Our own place in our own city has been out of view.”

The tour information has grown ambivalent about Odesa’s popularity as a hedonistic metropolis of crime — “another Russian-Soviet myth,” he says — immortalized by the fictional gangster Benya Krik in Soviet-Jewish author Isaac Babel’s Odessa Stories.

Vasyuta appreciates Babel, who was swept up by the Stalinist purges and executed throughout World War II, and infrequently takes guests to the author’s childhood neighborhood of Moldavanka, which within the early twentieth century was a middle of Odesa’s vibrant Jewish neighborhood. But he additionally contains stops by monuments and plaques devoted to Ukrainian politicians, poets and scientists.

“This war has made me want to show every single one of them,” he says. “The more the Russians bomb us, the more Ukrainian they make this city.”

After repeated Russian assaults final summer time broken dozens of cultural websites in Odesa, UNESCO added Odesa’s historic heart to its World Heritage List. Meanwhile, the Russian navy’s Black Sea Fleet, which had its headquarters in Sevastopol on the occupied Crimean Peninsula, has largely fled after Ukrainian assaults. Odesa’s port is exporting once more.

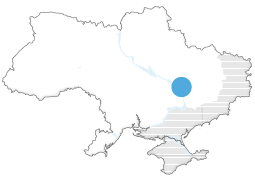

Dnipro

Parts of the maternity hospital in Dnipro have been broken when it was hit by a Russian missile in December 2023.

Claire Harbage/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

Parts of the maternity hospital in Dnipro have been broken when it was hit by a Russian missile in December 2023.

Claire Harbage/NPR

For greater than 30 years, Dr. Iryna Kulbach has delivered infants — “at least 15,000,” she says — at a big maternity hospital on this elegant central Ukrainian metropolis.

“Even during war, there is joy in a maternity ward,” the physician says. “We call it ‘the place of happiness,’ because isn’t happiness the smell of a newborn baby?”

Ecstatic new fathers typically spray-paint messages of affection on the partitions exterior. “Thank you darling for our little Andriy,” says one written in child blue.

Dnipro, which sits on a river of the identical title in central Ukraine, is about 100 miles from any fight zone, however it’s turn into a frequent goal of Russian assaults. Still, Kulbach believed — maybe naively she now says — that her hospital can be spared, regardless that Russian forces had hit so many others round Ukraine.

That all modified on Dec. 29, 2023. Kulbach arrived on the hospital as an air raid siren blared. The hospital’s workers and sufferers, together with 4 newborns, went right into a basement shelter. Then, as Kulbach was going into the shelter herself, a missile hit.

The constructing shook. She smelled smoke. The hospital was on hearth. Other medical doctors have been arriving on the hospital, together with Tetyana Andreieva.

“We were supposed to spend a few minutes exchanging New Year’s presents,” Andreieva says. “But everything was on fire. Broken glass from windows was falling from the sky.”

But everybody contained in the bomb shelter was alive. When Kulbach emerged, she noticed the dimensions of the destruction. The maternity hospital must be completely rebuilt.

On a latest afternoon, she stands exterior its ruins, that are cordoned off by a barbed wire fence. On the opposite facet, a younger girl waves.

“When are you opening again?” the girl asks. “I want to have my second child here, with you, at this place of happiness!”

The physician smiles however says later that she’s unsure when the hospital will reopen. Ukraine would not have the cash to rebuild it, she says, and assist from Ukraine’s allies seems to be shakier than ever. Kulbach needs to search out hope.

“Look,” she says, pointing to clawed-up earth lined with rubble. “That’s where a missile hit, and yet 50 meters away, I see children dancing in a playground.”

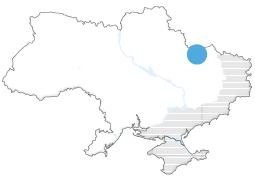

Kharkiv

People stroll in entrance of a historic constructing in Kharkiv that was broken by a Russian strike.

Claire Harbage/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

People stroll in entrance of a historic constructing in Kharkiv that was broken by a Russian strike.

Claire Harbage/NPR

Ukraine’s second-largest metropolis, simply 20 miles from the nation’s northeastern border with Russia, has been underneath bombardment nearly repeatedly because the full-scale invasion started two years in the past.

In the historic metropolis heart, the center of Ukraine’s mental neighborhood, the home windows of its modernist buildings are boarded up, although that does not imply the companies inside are closed. A patisserie that sells town’s signature cake, a chocolate-and-wafer delight referred to as Kharkivskyi, has solely closed for 3 weeks within the final two years of struggle.

“It is very important to feel like the city is alive,” says architect Max Rozenfeld. “Because, despite everything that’s happened to it, underneath the ruins and the pain, it is.”

Rozenfeld is amongst a gaggle of architects who hope to rebuild Kharkiv after the struggle, with the assistance of famed British city architect Norman Foster, the topic of Rozenfeld’s Ph.D. dissertation. The plan envisions Kharkiv as a metropolis for creatives and scientists.

It entails reconstructing bombed-out administrative buildings into inventive gems and creating an unlimited science hub in Saltivka, a neighborhood that invading Russian troops nearly razed.

“Some people are annoyed by this kind of talk,” Rozenfeld says. “They say it’s very irresponsible to sit in a shelled city and dream about the future.”

He understands. Each assault on Kharkiv appears like a physique blow to the soul. Rozenfeld brings up a household of 5 — the youngest was a 10-month-old child — burned alive on Feb. 12. Their constructing caught hearth after a drone assault by Russians on a close-by oil depot. Rozenfeld needed to give a chat the subsequent day.

“At first, I didn’t think I could do it,” he says, “because the tragedy was just so terrible. And then I thought, the more terrible the state of affairs, the more important it is to dream — to not lose hope.”

This struggle will not finish anytime quickly, he says, and its third yr is already bringing a sense of dread, he provides. Russian troops are advancing within the Kharkiv area. Rozenfeld additionally fears one other Donald Trump presidency, which he says would isolate Ukraine and assist the Kremlin.

“Kharkiv is a frontier city, and it’s always been able to adapt on its own terms,” he says. “Even after everything we have been through, it also has a place for its dreamers.”

Kyiv

People look out over Ukraine’s capital metropolis, Kyiv. Some sense of normalcy has returned to Kyiv, however lawyer Liudmyla Lysenko believes there’s a collective anxiousness that the Russians will come again to town.

Claire Harbage/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

People look out over Ukraine’s capital metropolis, Kyiv. Some sense of normalcy has returned to Kyiv, however lawyer Liudmyla Lysenko believes there’s a collective anxiousness that the Russians will come again to town.

Claire Harbage/NPR

Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv, all the time felt invincible to Liudmyla Lysenko.

She grew up right here, spending weekends exploring town’s giant, lush parks or the tree-filled islands on the Dnipro River. It was the middle of energy and politics.

Yet simply days after Russia’s full-scale invasion, Russian tanks and armored autos sat simply exterior town’s outskirts. Lysenko’s mother and father referred to as from the suburbs.

“They watched these terrible convoys passing by, counting something like 250 tanks,” she says. Those Russian troops would occupy cities exterior Kyiv, together with Bucha, Irpin and Borodyanka, and torture and execute residents, in line with witnesses.

Lysenko would by no means really feel protected in her hometown once more, whilst normalcy — busy eating places and bars, playgrounds full of laughing kids — returned. Beneath the normalcy, she says, there’s a collective anxiousness that the Russians will come again.

“They are our enemies because they want to kill us,” she says. “We realize that if we don’t defend ourselves, they will kill us all.”

Lysenko continued working, however her anxiousness exhausted her. Sometimes, when she got here dwelling, she collapsed on her mattress, unable to rise even for an air raid alert. She averted TV information, which spun a government-approved narrative that’s suspiciously upbeat.

“And then one day, for some reason, I turned the TV on,” she says, “and I saw this commercial for a course training civilians to defend themselves in case of another invasion.”

She signed up instantly. She dressed up in her warmest waterproof garments and drove to a secret location within the woods of the Kyiv area, becoming a member of a gaggle that included principally youngsters of their first yr of college.

An teacher handed out paintball weapons and first assist kits and started battlefield simulations. How to combat inside a constructing. How to defend your self within the forest. How to assist the wounded.

“You can’t hide from fear,” Lysenko says. “You have to face it, and then you won’t feel it.”

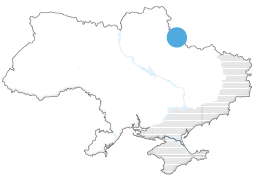

Sumy

Nataliya Kucherenko drapes a flag over the mattress in her son’s room within the Sumy area of Ukraine. He was captured by Russian forces in Mariupol and Kucherenko waits for him to be returned.

Claire Harbage/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

Nataliya Kucherenko drapes a flag over the mattress in her son’s room within the Sumy area of Ukraine. He was captured by Russian forces in Mariupol and Kucherenko waits for him to be returned.

Claire Harbage/NPR

Ukrainian POWs freed in prisoner exchanges normally cross via a checkpoint on this northeastern Ukrainian area, named for its principal metropolis, Sumy. When that occurs, Nataliya Kucherenko will get a notification on her cellphone from the social media app Telegram; she subscribes to a channel that displays the border for convoys.

Then she gently picks up a large Ukrainian flag printed with a photograph of her 25-year-old son, Vova, and heads to a most important street in her hometown, Krasnopillya, barely 15 miles from the Russian border. She unfurls the flag and waits, typically for hours, for the convoy to move.

“It doesn’t matter whether it’s raining or snow, or whether it’s hot, I wait,” she says, holding again tears. “I keep hoping he will be on that bus.”

Vova has been a prisoner of struggle in Russia for practically two years. He defended Mariupol, the southeastern port metropolis on the ocean of Azov that Russian troops destroyed and now occupy. She would not know the place or how he’s.

A yr in the past, Kucherenko discovered an unverified video and put up on-line suggesting he had been sentenced to life in jail in Russia.

“That destroyed me,” she says. She says she will be able to’t eat or sleep and has misplaced a lot weight that her neighbors say that it is like she’s been in Russian captivity herself. Her husband is on the entrance line, so she’s dwelling alone. She has stored Vova’s room simply as he left it.

Kramatorsk

A memorial is ready up among the many stays of Ria Pizzeria, a beloved restaurant in Kramatorsk that was hit by a Russian strike in June 2023, killing workers and prospects.

Claire Harbage/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

A memorial is ready up among the many stays of Ria Pizzeria, a beloved restaurant in Kramatorsk that was hit by a Russian strike in June 2023, killing workers and prospects.

Claire Harbage/NPR

Ukraine’s japanese Donetsk area has been preventing Russia for a decade, since Russia-backed separatists declared independence in 2014. The full of life metropolis of Kramatorsk, which stays underneath Ukrainian management, has realized to stay with the ever-present menace of Russian assault.

Its heart-and-soul heart was a restaurant, Ria Pizzeria, the place locals gathered for weddings, birthdays, christenings and reunions.

“This was our family,” particularly after Russia’s full-scale invasion introduced the struggle even nearer, says Iryna Savchenko, one of many co-owners. “It was a home not only for our staff, but also for our family.”

Ria Pizzeria grew to become a preferred spot not just for locals however for journalists and assist employees drawn by the struggle. Savchenko says it was a spot the place you can all the time hear laughter and music, irrespective of how grim the information exterior was.

“We didn’t think at the beginning of the full-scale war that we would be targets,” she says. “But we soon found out that everyone in this country can be a target.”

On June 29 of final yr, a Russian Iskander missile hit Ria Pizzeria. Savchenko had simply traveled to Kyiv when she received the decision.

“They told me everything was gone,” she says. She spent all evening driving again, arriving at 5 a.m.

“When we arrived, there was a lot of rubble, a lot of destruction,” Savchenko says. “I thought everyone inside was dead.”

The assault killed 13 folks, together with pizzeria workers, native youngsters and a proficient novelist and poet, Viktoria Amelina. Their pictures are in a small, flower-filled shrine exterior the pizzeria’s ruins. Dozens extra have been wounded.

Savchenko says the grief broke her. But she did not need the Russian assault to kill Kramatorsk’s spirit, too.

“We decided it would be good for everyone in town if we opened another place,” she says. Ria Pizzeria’s surviving staff needed to contribute to Kramatorsk’s financial system, whereas additionally honoring those that died.

Six months after Ria Pizzeria’s destruction, Savchenko and her companions opened a restaurant in Kramatorsk that is constructed partly underground. It’s referred to as Friends.

“We came up with the name right away, without any discussion,” she says. “Because it’s a place for our friends, those we know now, those who we will meet and, especially, those who are no longer with us.”

[adinserter block=”4″]

[ad_2]

Source link