[ad_1]

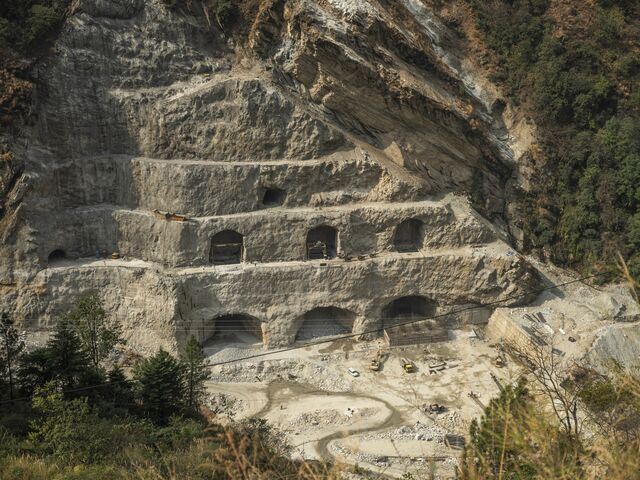

The Tapovan Vishnugad hydropower plant beneath building close to Joshimath, India. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/Bloomberg

Modi’s push to develop alongside India’s tense border with China heightens dangers to the already fragile space.

On January 3, 2023, cracks all of the sudden unfold over a whole bunch of buildings in Joshimath, India, and so they began sinking into the ground. Residents gathered up what furnishings and prized belongings they may and left. Over the course of some days, greater than 1,000 individuals sought non permanent shelter as snow lined what was left of their properties.

A yr on, the properties are nonetheless empty, with traces of life earlier than the collapse. A marriage picture album and a prayer scroll sit on one shelf; at a former lodge a pink signal reads, “A warm welcome awaits.”

Joshimath is simply one of many mountain communities perched dangerously between the rising impacts of local weather change and Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s plans for growing the area, that are coming into sharper focus forward of the nation’s elections this spring. Modi sees strengthening India’s contested northern border with China as important to nationwide safety, and hopes to show the Himalayas right into a renewable energy powerhouse. The area, dotted with holy websites, has robust spiritual significance for supporters of his Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party.

Himalayan Town Sits on Tense Border, Unstable Ground

This month alone, Modi and different top officials toured border cities, whereas Transport Minister Nitin Gadkari approved or inaugurated six main highway and rail initiatives within the area.

Yet heavy building on the world’s unstable floor, mixed with local weather change, has heightened the chance of catastrophe.

Standing at an altitude of 1,875 meters (about 6,100 toes) on a mass of compact however unstable particles often known as moraine, which is often left behind by a shifting glacier, Joshimath has all the time been susceptible to sinking as a result of terrain it was constructed on. The menace was idle for over a thousand years because the small metropolis welcomed tens of hundreds Hindu devotees strolling the Char Dham pilgrim circuit every season.

The space round Joshimath is residence to one of many military outposts alongside the disputed Sino-Indian border often known as the Line of Actual Control, the place India deploys round 20,000 troops and weaponry, and it additionally serves as a touchdown floor for personal helicopters.

Roads and railways are being constructed not solely to maneuver troops, but in addition to enhance connections with the remainder of the nation. One of the largest ongoing initiatives is the $1.5 billion, 890-kilometer (550-mile) Char Dham freeway in Uttarakhand state, which is able to join Joshimath to different mountain hamlets alongside a Hindu pilgrimage route.

Back within the early 2000s, India’s leaders noticed the Himalayan peaks as an efficient protection from a hostile neighbor. That modified when China ramped up infrastructure on its facet of the border. The BJP responded by matching its efforts, mentioned Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan, director of the Centre for Security, Strategy and Technology on the Observer Research Foundation in New Delhi. The celebration, in energy since 2014, positions itself as pro-development and in a position to stand as much as China and the West.

If Modi consolidates his power for a 3rd time period, Rajagopalan added, growth within the Himalayas will almost certainly intensify together with the spiritual messaging round it. “Most Indians are comfortable with the pro-Hindu narrative that Modi has been promoting across the region” by constructing temples and opening up new pilgrimage routes, she mentioned.

The gradual ascent up the foothills and away from Delhi, the world’s most polluted capital, was a certain respite from bad air. Today, clouds of mud from heavy building comply with the customer.

Near Dehradun, Uttarakhand’s capital, a newly widened highway snakes into the horizon, constructed on a dry riverbed and in opposition to a crumbling mountain wall. Beside a freshly excavated tunnel sooner or later this winter, staff gathered round a tin-roofed meals stall providing plates of rice and yellow curry. Once the venture is full, the journey to larger altitudes might be shorter.

Meanwhile, dams are multiplying. India’s electricity demand is surging, and the Himalayas are “endowed with hydropower,” says Rajnath Ram, an power adviser with the policymaking company of the Indian central authorities. The nation has 150 gigawatts of hydropower potential, of which simply over 50 is at the moment being exploited, he mentioned. “Our plan is to increase this figure to 68 gigawatts. We need hydropower in a big way to support our renewable energy,” he mentioned.

“Climate projections, we have included some” in planning, Ram continued. “But the specificity of this region still needs to be assessed. But we know that we have huge [hydropower] potential.”

Hydropower Development Boom within the Himalayas

Many initiatives on unstable terrain susceptible to landslides

Sources: Global Energy Monitor; Sharma, N. Okay., Saharia, M., & Ramana, G. (2023). India Landslide Susceptibility Map ILSM

According to Global Energy Monitor, India has greater than 100 new hydroelectric dams in planning or beneath building throughout the Himalayas — the right location to intercept enormous quantities of water flowing from the mountains’ melting glaciers.

A glacial lake — swelled by ice soften to the purpose of exploding — burst final October within the state of Sikkim. It prompted a sudden flood that killed not less than 40 individuals and destroyed the 1,200-megawatt Teesta III dam. A month later, a tunnel within the Char Dham highway venture collapsed after a landslide, trapping 41 workers for over two weeks.

An ambulance waits to hold staff from the location of collapsed tunnel in Uttarakhand in November. Source: AP Photos

Atul Sati, a Joshimath activist who has been advocating for the rights of its displaced residents, likens the brand new stage of danger to the affect of a big stone versus the pebble-sized danger of the previous. “If I throw a little stone at someone, it will damage them a little,” he says. “But if I throw a boulder, the damage will be on a different scale.”

Scientists say the extra weight of latest, large-scale infrastructure in addition to the common blasting of the mountains to create space for roads and tunnels will increase the hazard to Joshimath and different mountain cities.

In 2019, a landmark scientific review estimated that greater than 1 billion individuals throughout the Hindu Kush Himalayan area, spanning eight nations from Afghanistan to Myanmar, are uncovered to extra frequent and extreme climate occasions, together with flash floods, avalanches, landslides and droughts.

Arun Shreshta, a senior local weather specialist with the Nepal-based International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), says the issue isn’t growth in and of itself. “People need access to food, energy and all kinds of services,” he mentioned. “But it cannot be done without considering the impacts of climate change on different environmental scenarios.”

When new infrastructure initiatives are being deliberate, the authorities examine the impacts on the encompassing surroundings and attempt to mitigate them. Even so, Shreshta mentioned, “we are growing more concerned that the impacts of the environment itself on infrastructure are getting worse because of climate change.” Landslides and flooding occasions have all the time occurred within the mountains, however local weather change is exacerbating these dangers.

A venture’s danger publicity can’t be understood with out taking into consideration the potential for “cascading impacts,” he mentioned. For occasion, the collapse of 1 dam on a river would fire up a lot particles and sediment that it might overwhelm dams farther downstream. Still, he mentioned, that scope of evaluation “is something which normally project [managers] do not do.”

With what science tells us now, he mentioned, “rampant development anywhere you want simply is not going to work.”

The joint secretary for transport in India’s Ministry of Road Transport and Highways and the secretary in command of power for the chief minister of Uttarakhand didn’t reply to requests for touch upon authorities plans for transport and power growth within the Himalayas.

When Joshimath made headlines in January 2023, it was lined in snow. This yr, town and the encompassing mountains confronted a weeks-long dry spell that meteorologists name snow drought. Argha Banerjee, a glaciologist with the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research in Pune, mentioned that decreased snowfall contributes to the progressive shrinking of the Himalayan glaciers, which in flip alters the area’s hydrology.

For hundreds of years, glaciers have been replenished by snow falling from clouds caught amid the excessive peaks. But as temperatures rise from local weather change, ice retreats, releasing water that feeds increasing mountain lakes at decrease altitudes, generally hidden beneath the ice itself. This accumulation can result in flash floods, which grow to be much more disruptive as they lure sediment and particles on their race downstream.

“As we build more infrastructure in the region, we are likely moving closer to these susceptible areas,” Banerjee mentioned, and with so many incidents already occurring, “it seems like we are not using whatever environmental knowledge we already have.” As local weather change alters the mountain climate in unpredictable and violent methods which scientists are solely now beginning to grapple with, “What happens when we have to integrate the scientific knowledge we’ll generate in the next decade into planning decisions we make now?” he requested.

Geologist Piyoosh Rautela, the chief director of the Uttarakhand State Disaster Management Authority, a authorities physique, warned in a 2010 paper that catastrophe “looms large over Joshimath” due to haphazardly accredited hydroelectric initiatives. But now he says there isn’t a scientific proof that human intervention could also be contributing to the area’s subsidence, and that such theories are soundbites from the “environmental lobby.”

The space is traditionally susceptible to disasters; geological instability didn’t emerge with the development of latest roads, he mentioned. And highway initiatives must go forward as a result of the area is of strategic significance: “We share borders with both Nepal and China. If the need arises, we have to be able to move [military] forces.”

Disaster administration within the state is refined, he mentioned. Its mandate is to not advise infrastructure planners, however to boost consciousness about impending risks equivalent to geological shifting and even earthquakes, for which the division has arrange an early warning system in a position to warn a couple of main shockwave as much as 5 minutes prematurely.

For hundreds of years, Himalayan glaciers have been replenished by snow falling from clouds caught amid the excessive peaks. But as temperatures rise with local weather change, the ice retreats, releasing water that may trigger flooding at decrease altitudes. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/Bloomberg

Building pointers are additionally far more intensive than they was, in response to Rautela. Scientists are drawing detailed geological profiles of 25 hill cities, using distant sensing methods equivalent to laser-based LIDAR mapping, amongst different instruments. The downside, he mentioned, is that “with the kind of growth we are witnessing, you cannot have policing.” Compliance with the constructing guidelines finally ends up being voluntary and might solely be inspired by means of consciousness.

Around Joshimath, one can nonetheless make out historical footpaths: skinny, horizontal strains carved on the facet of the mountain. Wide sufficient just for crossing on foot, the perilous paths embodied the sacrifice required to succeed in enlightenment. Safer, wider roads had been later constructed to make Joshimath extra accessible, and its heart expanded round historical temples in a flurry of road markets, visitor homes and motels.

And whereas extra individuals can now full their journey alongside the Char Dham pilgrimage route, one in every of its sacred locations, the centuries-old Narsingh Temple, has began to visibly sink, together with so many different buildings.

The newest spherical of geological surveys has recognized new danger areas, and extra individuals have been suggested to maneuver away. But this time, many are resisting, saying that as town crumbles, they haven’t been provided a viable different to staying put.

The proprietor of the lodge with the pink signal, Laxmiprasad Sati, in his early eighties, and his spouse now lease a flat close by and spend their days watching over their outdated residence. They haven’t any plans to go away.

Lakshmi Devi, who was displaced from her residence, inside her non permanent dwelling. Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/Bloomberg

A lady in her mid-thirties named Lakshmi Devi is among the fortunate few who was resettled after the catastrophe in a village of steel buildings subsequent to the outdated city. She has arrange her new dwelling area tastefully, with a settee for guests to take a seat on whereas she makes tea and colourful posters on the wall, however she refuses to name it residence. The mom of three was a farmer and a home employee, however she is now devoted to native activism. Not trusting the federal government assessments, she personally surveyed about 400 properties for indicators of breakage.

Devi has but to see compensation for the lack of her home and the land she used to domesticate to feed her household, and regardless of her activism she has little hope it would ever come. “Without land to farm, what will we be doing?” she mentioned. “We are mountain people. We can’t go off and become something else.”

More On Bloomberg

[adinserter block=”4″]

[ad_2]

Source link