[ad_1]

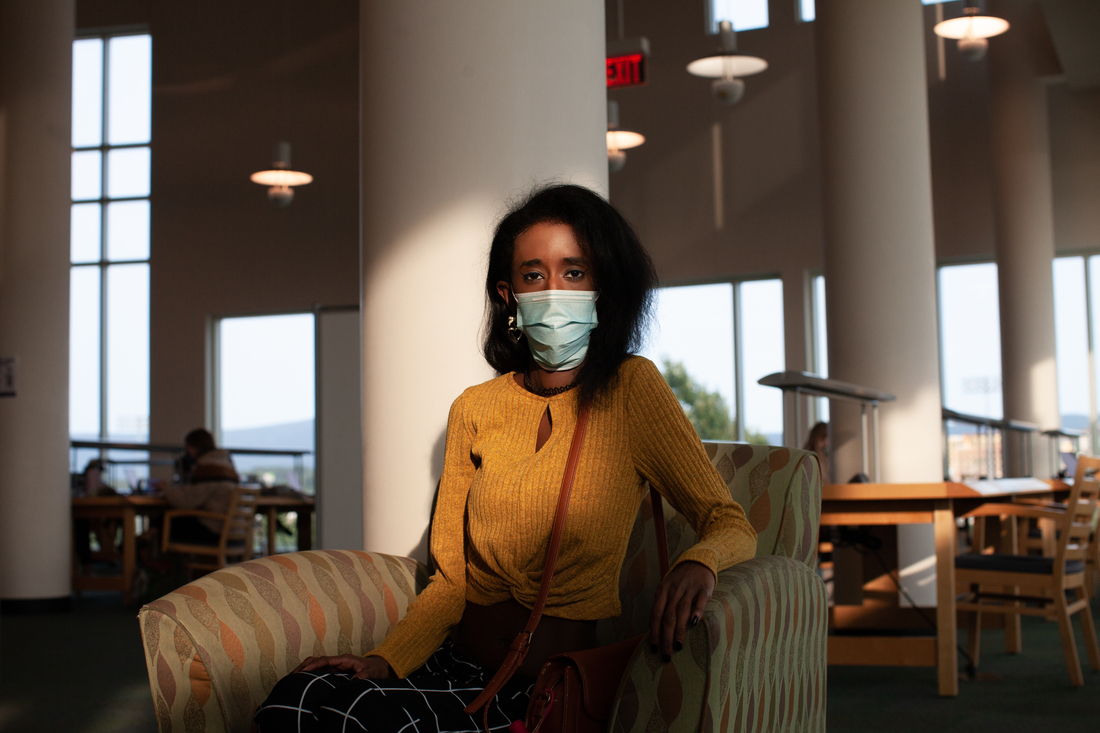

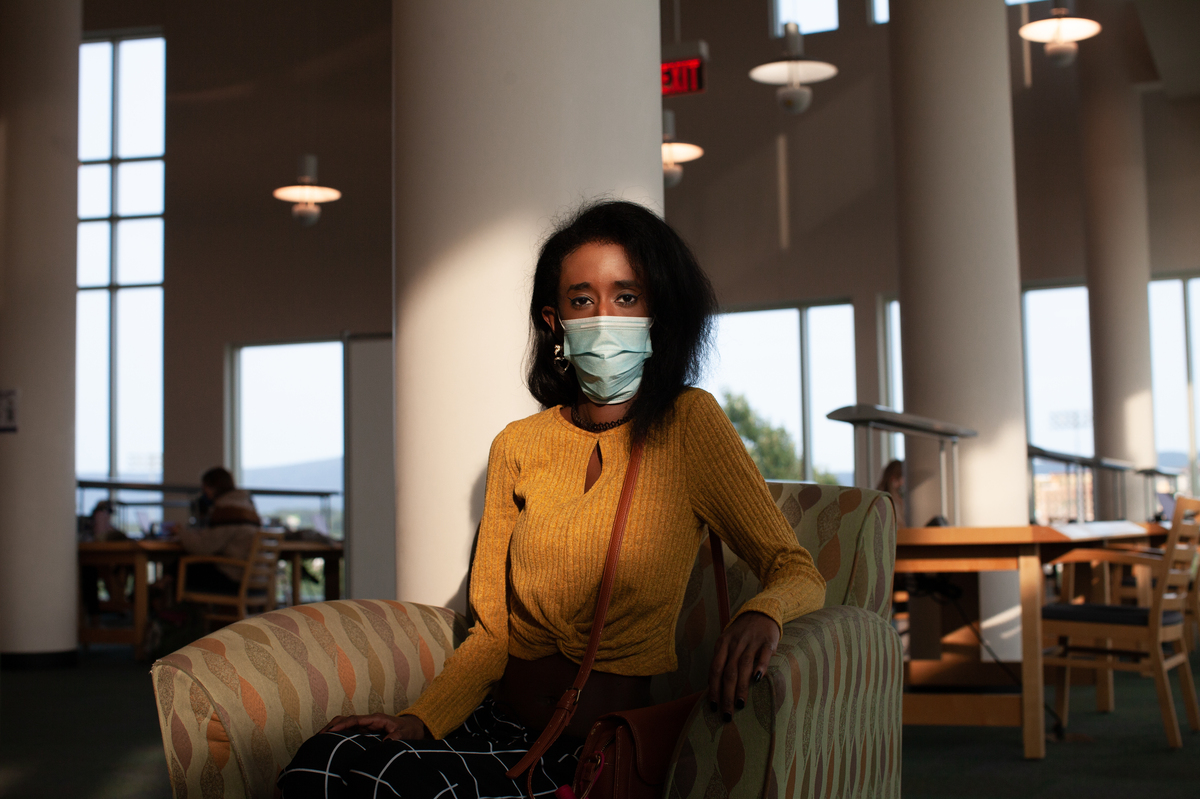

Huda Mohamed, a student at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Va., has an immunodeficiency. She decided to take extra precautions by using Virginia’s COVIDWISE app, which alerts users who may have been exposed to the coronavirus. Such apps are only available in a few states.

Eman Mohammed for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Eman Mohammed for NPR

Huda Mohamed, a student at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Va., has an immunodeficiency. She decided to take extra precautions by using Virginia’s COVIDWISE app, which alerts users who may have been exposed to the coronavirus. Such apps are only available in a few states.

Eman Mohammed for NPR

The United States is home to the world’s best-known technology companies, but so far the use of smartphones to fight the coronavirus has been tepid at best.

Smartphones have the potential to be a powerful tool in tracking the spread of COVID-19. They can tell you exactly how close you’ve been to other people, for how long and keep a detailed log of everyone you’ve been around for the last 14 days. Linked to testing systems, they can rapidly alert you if someone you’ve been in contact with tests positive.

Tech giants Google and Apple have teamed up to build a system that monitors potential exposures while keeping cellphone users’ identities anonymous. Health officials say smartphone apps could play a role in identifying coronavirus cases early and slowing the pandemic.

Many countries, such as Germany, Ireland and Singapore, have launched these apps nationwide with a lot of success. Yet in the U.S., such systems are available in just a handful of states and even there are only being used by a tiny percentage of the population.

When Virginia launched its COVIDWISE app at the beginning of August, Huda Mohamed downloaded it immediately.

“I figured it was a great way of keeping myself COVID-safe because I have an immunodeficiency,” says Mohamed, who is studying microbiology and dietetics at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Va.

And for her, an app letting her know if she had been exposed to someone who’d tested positive for the coronavirus was a no-brainer.

“I sent out mass text messages to my friends and family,” she says. “And I was like, ‘Download this app. This is important!’ I posted it on the JMU discussion boards.”

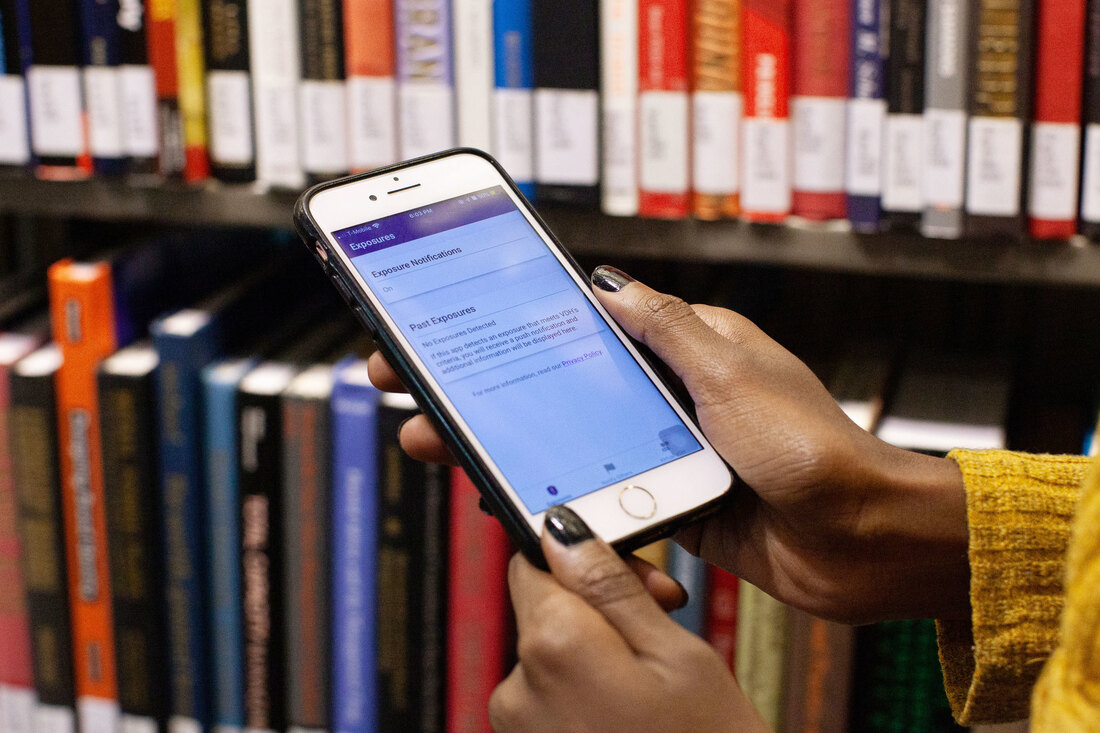

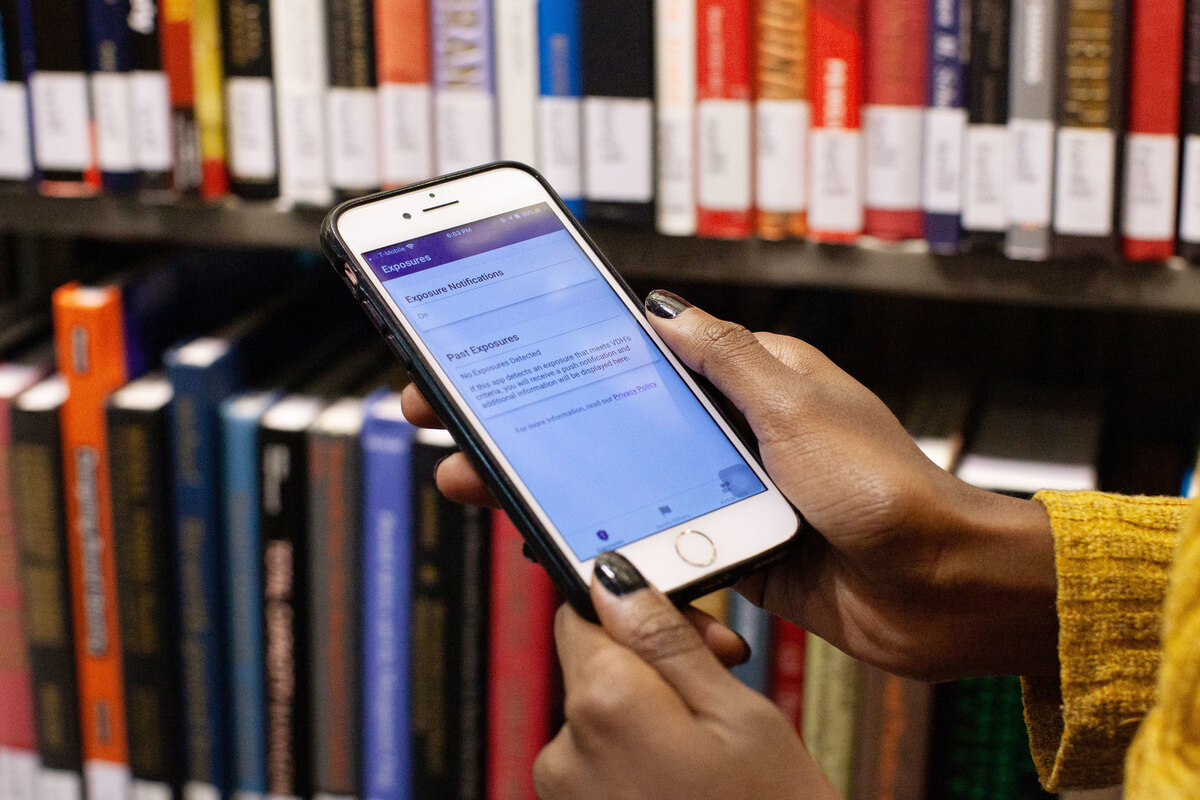

Mohamed checks the COVIDWISE app on her smartphone to detect if she has been exposed to the coronavirus.

Eman Mohammed for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Eman Mohammed for NPR

Mohamed checks the COVIDWISE app on her smartphone to detect if she has been exposed to the coronavirus.

Eman Mohammed for NPR

The COVIDWISE app works using the platform developed jointly by Google and Apple.

It swaps Bluetooth signals with other phones around it. But it only interacts with the phones of people who’ve opted in to the system and have their Bluetooth on. It keeps track of those encounters for the last 14 days, but to protect each user’s privacy, it doesn’t record the exact time, location or phone number of the devices.

So long as Bluetooth is turned on, it runs in the background. For weeks, Mohamed wasn’t even sure the app was working. “I would be out and about, and I would wait for the notification,” she says. “But the notification never came.”

Then the fall semester started at James Madison University. Students flooded back to Harrisonburg. Campus reopened. And soon there were more than 1,000 new COVID-19 cases at the university. Officials were forced to halt in-person classes.

That’s when a notification popped up on Mohamed’s phone saying she’d had 12 potential exposures.

“It was a little scary,” she says. She’d been trying to limit her outings to essential activities. She hadn’t been out to large gatherings, and she couldn’t figure out why she had so many potential exposures all at once. “And I started in my head retracing my steps, thinking about who I was around that day.”

Despite that initial notification on her home screen, when she opened the app it listed zero exposures. Mohamed wasn’t sure what to do. She doesn’t have health insurance or a doctor to call. She decided to self-isolate for a bit and retreat from the world.

“I’ve been avoiding people this week,” she said in early September.

Mohamed got a frightening alert on her phone about 12 potential exposures. It turned out to be a confusing weekly push notification from Apple, which the company has since fixed. The alert was not an official notification from the Virginia Department of Health.

Eman Mohammed for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Eman Mohammed for NPR

Mohamed got a frightening alert on her phone about 12 potential exposures. It turned out to be a confusing weekly push notification from Apple, which the company has since fixed. The alert was not an official notification from the Virginia Department of Health.

Eman Mohammed for NPR

It turns out she didn’t have to do so. The push notification was from Apple about potential exposures being analyzed by the system. It was not an official exposure notification from the Virginia Department of Health. That would have only been sent out if she’d spent at least 15 minutes within 6 feet of another app user who’d recently tested positive.

Jeff Stover, an epidemiologist at the state’s health department, says the weekly push notifications from Apple have caused some confusion. Apple is aware of the issue. It says the initial language on the push notifications, which is what gave Mohamed a fright, is being updated and clarified.

Virginia is by far the national leader in the use of these apps. So far, more than 500,000 people have downloaded the state’s app. Stover says despite some of the initial confusion about the push notifications, the rollout is going well. And he says the app can reach people whom traditional contract tracers would never track down.

For example, Stover says, if he had gone to the local hardware store and “stood in line for 15 minutes because it was just taking awhile and I ended up being positive, I have no idea who that person was in front of me in line. At least through an exposure notification app, that person might get an exposure notification.”

But very few people are getting those notifications.

Since Google and Apple launched their platform in late May, the U.S. has recorded more than 4.5 million additional cases of COVID-19. These smartphone systems have sent out alerts on only a few hundred of them across the 11 states that are using them. Eight of the states are using the Google/Apple Bluetooth platform. Three others have released apps that use GPS tracking similar to the system used in China. Beijing has used cellphone tracking to lock down anyone who might have been exposed and to cut off transmission of the disease.

But there have been greater privacy concerns about the GPS-based apps and far fewer downloads. The Google/Apple system is only available to government health departments. Each state must choose to opt in and then build or buy its own app.

“That really comes back to how public health operates in the U.S.,” says Vivian Singletary, director of the Public Health Informatics Institute in Atlanta, which has hosted several forums for public health officials on this technology. The U.S. doesn’t have a national health care system. And health, like education, is dealt with primarily at the local rather than the federal level.

“We do not have national public health law, per se, that governs everybody across every state,” Singletary says.

So, short of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issuing an app, each state has had to build its own. For many state health officials, already overwhelmed by the pandemic, this hasn’t been a priority.

And there have been other impediments. All the state-issued apps require relatively new smartphones. That could make them less effective among older residents who are most at risk from the disease, Tennessee health officials say.

Other critics say the alerts provide so little information that they’re not worth the trouble. The alerts don’t tell the user exactly when, where or to whom they were exposed. They don’t even disclose exactly when a person tested positive. It may have been 13 days ago, and you may have been wearing a mask at the time. While these apps could provide more details on the exact time, location and duration of the exposure, they don’t.

“I think I expected more [from the app], honestly,” says Mohamed, the college student who was initially excited about COVIDWISE. She says the app only does the bare minimum. “I expected it to actually notify me when it happened, not a week later.”

“I think I expected more [from the app], honestly,” Mohamed says.

Eman Mohammed for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Eman Mohammed for NPR

“I think I expected more [from the app], honestly,” Mohamed says.

Eman Mohammed for NPR

And the state-issued apps still don’t work across state lines. A nationwide database is being developed to tie them together, but currently if you’re visiting a neighboring state, the system doesn’t function. And even though Apple and Google have put a priority on privacy protection, many people still say they don’t trust the technology.

Consumers and even information technology professionals still have high levels of concerns about these apps collecting personally identifiable information on their users, according to a recent poll by IT security firm SecureAge.

Still, more states are planning to launch apps in the coming weeks. Pennsylvania is the latest to roll one out. Maryland is expected to release one soon. As more people start using the apps, public health officials say they’ll become more effective and eventually could become a tool to help with contact tracing but won’t replace it.

[ad_2]

Source link