[ad_1]

Before each football practice in which he coaches, Danny Schaechter removes his gold wedding band and loops it onto a chain draped around his neck. Years ago, he learned a hard lesson when a football smashed into his open hands with such velocity that it cracked the ring, subsequently punctured the skin and sent blood dripping down his palm.

That pass wasn’t launched out of a ball machine. It came from the arm of a 16-year-old high school sophomore named Caleb Williams. Schaechter returned home to his wife, told her the story and then heard an earful. Her anger gave way to shock and, finally, awe. “How does that even happen?” she asked. “This kid is good, isn’t he?”

Behind the tall, black metal gates of Gonzaga College (Washington, D.C.) High School, the legend of Superman has been rewritten. In this version, there is no red cape, no green kryptonite. Only a teenage quarterback: a Hail Mary–throwing, swaggy-dressing, uber-talented kid with the power to split metal.

As his powers emerged, the nickname grew. Superman.

There were the sack-escaping, 360-degree pirouettes followed by a perfectly placed 40-yard completion. There were behind-the-back passes—no, really, there were—and there were back-shoulder throws of NFL caliber. The out-route passes were spectacular, and the long balls were things of beauty.

Williams seemed to see plays before they happened, leading his receivers to an exact point, always with a tight, spinning spiral thrown with such force that it stung the hands. There were the plays on the ground, too, the games when he scored a half-dozen rushing touchdowns in a way that reminded some of Cam Newton. In one game, Superman ran for a touchdown, caught a touchdown and threw for a touchdown.

But of all the extraordinary plays, of all the rousing victories, one stands alone. On the final pass of his sophomore season in 2018, Williams completed a 53-yard Hail Mary to earn his team a championship. “That’s part of his legend here,” says Randy Trivers, Williams’s head coach at Gonzaga, an all-boys Catholic school in the nation’s capital.

On this cloudy Tuesday, three days after their Superman—as a true freshman—replaced a Heisman Trophy favorite and marched Oklahoma to a wild comeback over Texas in one of the most memorable chapters of the Red River rivalry, this place is abuzz.

On one of the biggest stages possible, their legend introduced his legacy to college football. A handsome, fashionable kid with a strong social media presence, Williams, many believe, could be the new face of a changing game—one of the first breakout stars since the NCAA lifted restrictions on athletes entering endorsement deals.

Arguably the No. 1 ranked quarterback recruit in the 2021 high school class, Williams made the bold choice of signing with a program that employed not just an incumbent starter but also a projected first-round NFL draft pick, and has already, it seems, usurped that person.

Superman has arrived. “It’s amazing,” says Ed Donnellan, a social studies teacher at Gonzaga who tutored Williams. “What do you do if you’re [Sooners coach] Lincoln Riley?”

That quandary is one of the more high-profile in the sport right now. The Oklahoma student newspaper caused controversy within the program earlier this week when it reported that Williams, not Spencer Rattler, was taking the first-team snaps in practice. The reporters say they gathered the information from a public building with a view into the Sooners’ practice. OU promptly canceled all team media availability on Wednesday, a presumed response to the news emerging.

Most feel the Sooners are closely guarding a secret that’s been obvious to many for a while. Williams enrolled at Oklahoma a semester early, competed in spring practice and out-performed Rattler in the spring game, completing all but one of his 11 passes for 99 yards. In an earlier game this season, as Rattler and the offense struggled, the OU student section broke out chants of “We want Cay-Leb.”

“He’s as talented or more talented than Rattler,” says John Marshall, a defensive back for Navy and a former pass-catcher at Gonzaga.

So when Williams entered in Saturday’s second quarter with Oklahoma down 28–7 to Texas, ran for a 66-yard touchdown on his first play and roared his school back to victory, few who knew him were surprised.

“He’s Superman,” says Aaron Turner, another one of Williams’s high school wideouts, who is now playing at UConn. “He saves the day.”

Sam Sweeney likes to brag that the only thing that stood in his way of being a high school starting quarterback was a kid they refer to as Superman.

After all, who beats out Superman?

As a rising junior at Gonzaga, Sweeney was poised for years of hard work to manifest into the starting job for the Eagles, a football powerhouse in one of the country’s most famed high school divisions, the Washington Catholic Athletic Conference. Sweeney led workouts as the No. 1 quarterback during the spring, over the summer and in preseason camp. But at Gonzaga’s opening game, he found himself watching from the sideline after coaches started Williams, a freshman.

“I questioned it a lot,” Sweeney says. “Then, after the season, Caleb got, like, 10–15 scholarship offers and I was like, ‘Well, O.K.’ ”

In fact, before Williams even started a high school game, he received an offer from Maryland. More incredible is that just three years before that, Williams was playing running back at the youth league level until his arm strength convinced the player himself, as well as his dad and coaches, that little Caleb needed to move positions.

Kevin Holmes, who oversaw Williams’s youth team, the Bowie Bulldogs, sums it up quite nicely: He threw like a grown man. He punted and kicked like one, too. Holmes is still convinced that his former quarterback could boot 50-yard field goals and 40-yard punts for the Sooners if they needed him to.

Around the time Caleb switched positions, his dad, Carl Williams, opened a sports training and recuperation facility in Maryland called Athletic Republic, the first step in sculpting his son’s body into what we see today—a big, fast, powerful specimen that reminds some of Dak Prescott and others of Patrick Mahomes. Mahomes, though, isn’t as thick, nor is he as quick as Caleb, says Schaechter, without a hint of sarcasm.

As a high schooler, Caleb had a support team that would rival many NFL passers. He not only had access to the family-owned training facility, but also had a strength and conditioning coach, multiple passing instructors and a dietitian, his father. When he began playing quarterback, Carl put his son on a diet to keep him fit to play the most important position on the field.

Carl, an entrepreneur and businessman, didn’t force his son into football, family friends say. Caleb forced himself into that, embracing a desire at an early age to be a Division I quarterback. The Williams family’s lives became geared around it. At some point, the family at least temporarily moved into an apartment with a balcony that overlooked Gonzaga’s on-campus football field, and they now split their residences between Norman, Okla., and the D.C. area.

“He’s a type of dad, if you have a dream and goal, and you do the work, he’ll support it,” Holmes says of Carl.

That included sending his son to Gonzaga, one of D.C.’s premier academic institutions, at a cost of $25,000 a year. Founded by the Jesuits in 1821, the school is nestled in the heart of the city, one mile due north of the U.S. Capitol, close enough that students were evacuated during the Jan. 6 insurrection.

Black gates separate campus from the hustle of the D.C. streets, and security guards monitor entrance points. A 162-year-old church, St. Aloysius, rises from within campus walls and serves homeless people breakfast and lunch while turning into a shelter in the winter.

Gonzaga’s nearly 1,000 students abide by a strict dress code: slacks, dress shoes and collared shirts. Enrollment is controlled. A 12-person committee admits about one-third of applicants each year. “Getting in,” says Trivers, “that’s the hard part.”

In his first year at Gonzaga, Caleb Williams led the Eagles to the Washington Catholic Athletic Conference championship game. They lost. As a sophomore, he led the Eagles back to the title game against Maryland powerhouse DeMatha.

Gonzaga fell into a 20–0 hole and rallied out of it to set up an electric finish. Three touchdowns were scored in the final 29 seconds. Gonzaga took the lead on a Williams touchdown pass before DeMatha returned the ensuing kickoff for the go-ahead score.

And then, as time expired, the man they call Superman heaved a pass toward a gaggle of players in the end zone. The ball came whistling into the arms of a leaping Marshall for an unthinkable victory. A two-minute clip of the game’s final seconds has been viewed more than a half-million times on YouTube.

The play is immortalized in such a way on campus that it is used as a greeting. At the start of an interview this week, athletic director Joe Reyda leans across his desk and, in a hushed tone, says, “So you know about the Hail Mary, right?”

The last time Aaron Turner visited his friend Caleb Williams’s bedroom, about a year ago, something quickly caught his eye.

Shoes.

They stuck out from everywhere—from the closet, from shelves, strewn across the floor. At that time, Turner believes Williams had more than 100 pairs of shoes, and he estimates that number has climbed.

Williams is deep into the world of fashion. Instead of a bland and boring suit, his gameday outfits fall in line with the latest trend in fashion—New York street style. Friends describe his look as swaggy and altogether unique.

Good luck catching Williams wearing the same ensemble in the same month. He has bins and bins of clothes, says Turner. One day, it’s designer jeans, a plain white T-shirt and custom Jordans. The next day, it’s cargo pants, a flannel shirt and Yeezys.

This Superman is no spectacle-wearing, buttoned-up Clark Kent.

“He can pull it off,” says Nate Kurisky, a senior tight end at Gonzaga who caught passes from Williams. “He looks drippy.” Williams makes a statement with his clothing, Marshall says. What’s it say?

I’m not like the rest.

The statements go beyond clothes. For instance, Williams paints his nails. For the game against Texas, he painted an upside down Longhorns logo on his right pinky and index fingers. On his ring finger, he painted a black “F” and on his middle finger was a black “U.”

Turner says he looks up to the nail-painting swag of rappers A$AP Rocky and Tyler, the Creator. Williams is a big rap guy. His pinned tweet is a message he posted on July 3, one made famous by Jay-Z: “I’m Not a Businessman; I’m a Business, Man!”

Between Instagram and Twitter, Williams has nearly 100,000 followers. He interacts with fans on both platforms, at times holding IG Live sessions, and tweeting on a daily basis. It’s not all about football. His Instagram page is full of shots you might find on a fashion model’s website.

And that’s not a bad thing. In an era when athletes can profit from their name, image and likeness (NIL), Williams is already ahead of the game, says Jim Cavale, the CEO of INFLCR, a digitally based NIL company. He is driving fans to his platform not just through football, an important aspect in an athlete’s brand development. Athletes who profit the most from NIL are those who work to develop their brand and those who have on-field success.

“The magic is when somebody has both,” Cavale says. “Caleb is a guy who really gets it. That’s the key—thinking about these massive audiences tied to non-sports things.”

On the back of preseason hype, Rattler reeled in NIL ventures. He has a trading card deal, signed an endorsement contract with Louisiana-based chicken restaurant Raising Cane’s and was given two vehicles by a local Oklahoma automotive group.

Experts estimate that he’s earned around $200,000. His on-field struggles present one of the first quandaries for companies who poured money into the expectations and predictions bestowed onto college-aged kids. But the question, Cavale says, isn’t what happens to Rattler—it’s what happens to Williams?

He seems to have been preparing for this moment. Williams filed four trademark logos in August, one of which is a Superman logo emblazoned with his initials, CW, instead of the traditional “S.”

“He can now take advantage of his shining stardom and capture midseason deals that have the potential of far eclipsing that which Rattler has been able to command,” says Darren Heitner, a sports law attorney in Florida who represents players in NIL ventures. “If he maintains his position as the starting quarterback and continues to excel on the field, then six figures in NIL deals may be a given.”

During the Red River postgame, Riley denied a request from ESPN to interview Williams. While it’s somewhat normal for major college coaches to prohibit true freshmen from speaking to reporters, in the NIL era, the move is catching more criticism. Is the coach hampering his star player’s potential exposure and future NIL deals?

“What if a player does [an] interview despite coach edict?” asks Heitner.

Riley’s prohibition expands beyond Caleb himself. Reached earlier this week, Carl Williams politely declined comment through a text.

“The Great John Thompson had a policy of not allowing freshman interviews,” Carl wrote. “We are fully supportive of Coach Riley’s no freshman interview policy and it extends to us as his parents as well.”

Donnellan, the social studies teacher at Gonzaga, raises the small glass jar so a reporter can see its contents. Dirt. But this is special dirt, Donnellan says, brought to him by Caleb Williams from a cemetery in south Louisiana.

During a recruiting trip to LSU, Williams left the Baton Rouge campus, drove about 30 minutes outside of town and spent an afternoon with the descendants of the Georgetown 272, a group of 272 enslaved people in Maryland who, in 1838, were sold to Louisiana plantation owners. Before being sold, the slaves labored at five plantations that financially supported the school of Gonzaga, something Williams and other students learned in Donnellan’s class. A couple of those enslaved people even worked at the school.

The dirt in the jar is from the cemetery where those slaves are buried, captured by Williams during his visit.

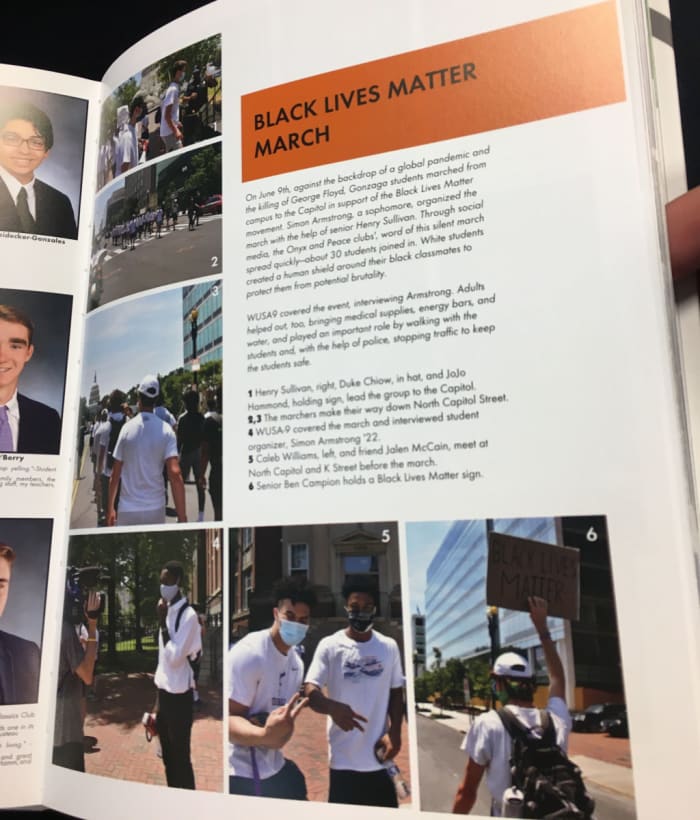

For Donnellan, it’s an example of Caleb Williams beyond football. In fact, in the Gonzaga yearbook, Williams is prominently featured on a page celebrating the Black Lives Matter movement. Last summer, he and others marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in a sign of unity.

“He feels free to express himself. He feels free to be who he is,” says Meaghan Tracey, a counselor at the school and one of those closest to Williams.

But there’s no denying that the quarterback’s world revolves around the sport. It was crushing last year when Gonzaga pushed its fall season to the spring because of COVID-19. It meant Williams would not play a senior football season. He moved to Norman in the winter.

While in Norman last spring, he was enrolled dually at both Gonzaga and OU, something only made possible because his high school remained in virtual learning. He completed high school classes virtually and attended college classes at Oklahoma, all while participating in the Sooners’ spring practice as QB2 behind Rattler.

“We talked about how he would be playing behind a Heisman Trophy candidate,” says Tracey. “He wasn’t worried about it.”

Maybe Williams knew something we didn’t. Maybe he knew that he’d turn a sliver of an opportunity in what is annually OU’s biggest game into one of the most stunning performances of the 2021 college football season.

He’s a long way from joining the elite quarterback trio that Riley has tutored in Norman—Baker Mayfield, Kyler Murry, Jalen Hurts—but he’s closer now than he was last week.

“He’s a once-in-a-generation player,” Turner says. “You guys are going to see in the weeks ahead.”

Schaechter has spent the last month instilling confidence in Williams with motivational texts. Control what you can control. He wasn’t used to riding the bench. He was frustrated. He was champing at the bit, Schaechter says. “He knew he could do it and do it better.”

Finally, he got his shot. Roughly three years after a high school sophomore cracked his wedding band, Schaechter watched a kid whistling the same passes on national television inside the Cotton Bowl.

“Oh, I remember that,” Sweeney says, recalling the story of his teammate’s metal-splitting pass. “Coach was like, ‘I can’t believe he broke my wedding ring!’ I saw it and was like, ‘Jesus!’ ”

No, Superman.

More College Football Coverage:

• Rattler, Williams and the NIL Impact of Red River Thriller

• Oklahoma’s Counter Unlocks Dangerous Rushing Offense

• Evaluating the Best College Football Rivalries

[ad_2]

Source link