[ad_1]

Colt Brennan’s parents were in Mexico for a wedding on a Saturday in early May when they started worrying about him again. A friend who fed their pets while they were away had been surprised to find a backpack in their foyer and heard music coming from somewhere inside the house. Colt’s parents called and texted him. He didn’t answer.

That Sunday, Colt’s last day alive, Betsy and Terry Brennan flew back to their home in the hills above Orange County, where a sign by the door announces ALOHA! Inside, they heard noise coming from the kitchen and found their 37-year-old son sprawled across a small sofa. Drunk and high, watching TV, he was surrounded by two bottles of vodka, some beer cans and several nitrous oxide containers.

Betsy groaned. Not again.

Colt, one of college football’s all-time great quarterbacks—and one of the game’s truly beloved figures—had struggled with alcoholism and drug addiction. He tried everything to get sober, and then, recently, seemed to get there. To those close to him, in the few months before his parents returned, he appeared as healthy as he’d been in a decade.

Back in Irvine, though, Terry guided Colt to his SUV and drove off. Father and son didn’t speak. The silence felt like a scream. Overwhelmed with emotion, Terry wanted to cry, to “kick his ass,” to hold his son—to do whatever he could to stop the thing that kept driving Colt back to this. The sun was setting. Terry didn’t know where to go or what to do. He wondered, as so many addicts’ parents and families and friends have at some point, maybe many times over: Is this ever going to end?

Statistically speaking, Colt Brennan’s getting sober would have been an aberration, not the norm. Twenty-two million Americans have active substance abuse disorders. Only 10% get help. And of that group, only 10% stay sober after finishing a treatment program. While that’s a lot of people getting sober, there are tens of millions more who remain addicted. In 2020, the number of U.S. deaths by drug overdose hit an all-time high: 93,331.

But Colt had seemed to be doing well. He was four months into a five-month program where a reported 64% of graduates stay sober, and he believed he finally had a sense of what caused his addiction, and why it was so damn hard to stay clean. Much of it came down to one thing: “pain,” says a friend from that program. “Heartache. Misery. Feeling alone in the world. Specific traumas and feelings that you don’t want to talk about until you get the strength.”

In a journal he began writing during his last few months alive, Colt said he believed that he wasn’t addicted to any substance in particular, but to what any given drug might provide him: “Escape.”

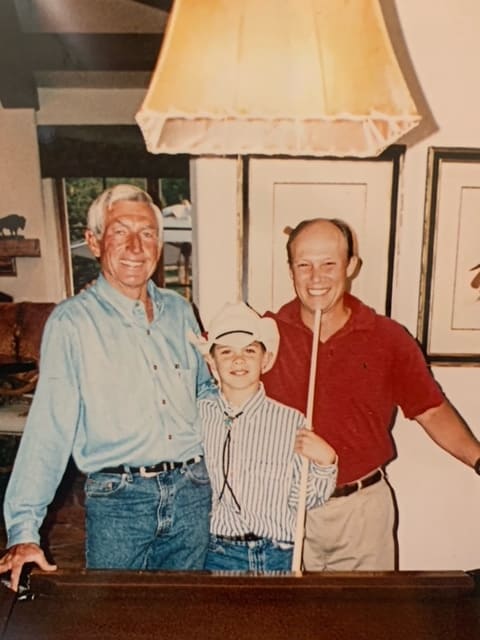

Colt had been a happy kid with a big heart; one who loved hard—“so passionate,” says his older sister, Carrera. He loved animals, especially Poncho the family beagle. He loved In-N-Out, always ordering fries, a Coke and the off-menu “3×3” burger. And he loved the man he called “Papa”—Boyd Jefferies, the father of Betsy’s first husband. On Papa’s ranch in Aspen, Colt rode horses, fired guns and camped under the stars. Papa took Colt on a cattle drive once, guiding a herd from Utah to Colorado, and later Colt, weighing his whole life, filled pages of his journal with story after story about the man who taught him to trust himself. Who braved hurricanes to save sea turtles in St. Martin, and tipped waiters hundred-dollar bills, and one day, in Anguilla, decamped for hours with Colt at a beach shack, musing on island life, listening to Bob Marley and drinking beer. “He would inspire into me that life was all about experience to the fullest,” Colt wrote. “He was the most influential relative in my life.”

All of that, and he loved football. He went to his first game when he was 3, in a full Los Angeles Rams uniform, watching a cousin play for Mater Dei High in L.A., running around the field afterward and begging Terry to buy him the stadium. By 4 he was a Monday Night Football obsessee. Show-and-tell was always about the sport. His teachers would call his parents and say, “He’s doing great—but we gotta get off the subject of football.” And his passion for the game made him great at it. At Mater Dei himself, as a junior, Colt backed up future Heisman winner Matt Leinart. Named the starter his senior year, he couldn’t wait for Papa to see him play.

Brennan was football-obsessed as far back as his parents can remember.

Courtesy of the Brennan family

That never happened. Shortly after the beach day in Anguilla, two weeks before Colt’s senior season began, Papa suffered a fatal aortic aneurysm.

Mater Dei started 1–3 as Colt bounced passes off the ground. Nothing felt right. His head pulsed, as if a broken heart had bruised his mind. College recruiters lost interest. He graduated, spent a year at a Massachusetts prep school and walked on at Colorado, three hours from Papa’s old ranch, where Colt thrived on the Buffaloes’ scout team until he drank too much one night and made some catastrophic decisions. According to a police report, he entered the dorm room of a female student he knew. She said he exposed himself and forced himself on her until he was interrupted by her roommate. He was later arrested.

As the legal process played out over the course of a year, Colt moved back home with Betsy and Terry in Irvine and played for Saddleback Community College.

A charge of unlawful sexual contact was ultimately dismissed, but felony first-degree trespassing and second-degree burglary charges were not, and Colt was sentenced to 60 hours community service, seven days in jail and four years of probation. He was a convicted felon, and would be all his life. He served his sentence over spring break, one night sharing a cell with a man who’d been convicted of attempted murder. “He never really got over [that incident],” Carrera says. “It weighed on him a lot. It kind of haunted him.”

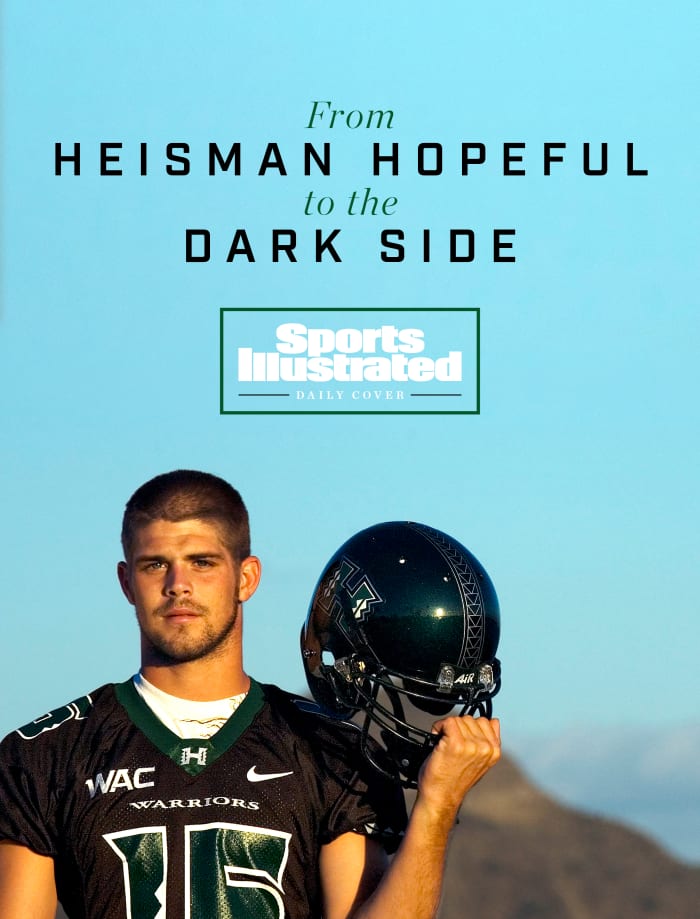

He would get a shot to move forward. Hawaii coach June Jones was watching film of a Saddleback receiver when he noticed Colt’s mobility and gunslinging accuracy. Reminded of a young Dan Marino, Jones offered up a walk-on spot. And Colt—in love with Hawaii’s run-and-shoot offense, and seemingly born for island life—made the most of this second chance. He proved nimble and electrifying, more than capable of tucking and running for quick gains; and he was a brilliant passer, throwing with a fluid, snappy, almost-casual side-arm.

As a junior he set a single-season NCAA record with 58 passing touchdowns, leading pundits to project him as an early-round NFL draft pick. Then he shocked everyone by saying he wasn’t ready to leave Hawaii yet. “I’m so grateful for this place,” he gushed about his adopted home.

In 2007 he became Hawaii’s first Heisman finalist (he finished second), and he led the Rainbow Warriors to their first undefeated season and first BCS bowl game. In the end, he walked away with 31 NCAA passing records, including 131 career passing touchdowns. On the islands, says Davone Bess, Colt’s primary receiving target, he was treated “like a rockstar.”

His engagement schedule eventually grew so full that he needed an assistant. He gave motivational speeches at schools and at juvenile detention centers, about making good choices and growing from bad ones; and he helped promote local businesses. “He always did everything for everybody else. … He just wanted to make everybody really happy,” says Jacky Bruder, who got Colt to help out with his lifestyle and apparel brand, Barefoot League, and volunteer for the youth football team he sponsored. “In Hawaii, his legacy will always live because of what he did for us.”

Along the way, Colt even found love with a local girl named Shakti Stream, a fellow student who’d been raised in the jungles of Kona, the Big Island. He seemed happy.

But Carrera saw hints of trouble. When her brother would visit, he’d start most days smoking weed; and when they drank together, he’d always “go next level,” she says. He told her he felt traumatized by what happened in Colorado. Anything good, he said, could turn to pain. “He just never seemed comfortable being sober,” Carrera remembers.

In his final season at Hawaii, Colt hurt his hip and his ankle, and he suffered at least one concussion. His draft stock dropped and Washington scooped him up in the sixth round, only to discard him after two years, following two hip surgeries, two knee surgeries, and not a single regular-season snap. The Raiders signed him in 2010 … and released him a month later. One source with knowledge of Oakland’s dealings around that time says that coaches had already picked up on Colt’s budding struggles with addiction.

Waiting for another bite, Colt moved back to Kona with Shakti, where they lived without electricity on Hualalai, an active volcano. “A simple but incredibly fulfilling lifestyle,” Colt wrote. “[We] seemed content and happy.”

In so many ways, the morning of Nov. 19, 2010, captured that. Colt and Shakti woke up and went to yoga at 5:30 a.m. They shared a coconut with their teacher and headed off to play volleyball. On the way, they stopped for breakfast, then Shakti drove her Toyota 4Runner while Colt ate—and as he browsed through pictures on her phone, Shakti said she wanted to show him a video. She took the phone, scrolled, tapped.

And then Colt woke up a week later, an island away, in Queens Hospital on Oahu.

According to the accident report, Shakti had drifted into oncoming traffic and hit a car at 60 mph. Everyone survived, but Colt broke an eye socket, a leg, a collarbone and every rib on the left side of his body. (One passenger in the other car ended up in a coma for a week.) As the 4Runner rolled, his skull cracked against the door frame, leaving his brain with six hematomas. And that was just the physical damage. The real pain would manifest in a new inability to simply move through life.

Back in Irvine, at his parents’ home, Colt recovered—but “everything I once was,” he wrote, “disappear[ed].” Sleepless and struggling to cope, he was prescribed Trazodone, an antidepressant and sleep aid. He tried going without it, but quickly he was in the drug’s grasp, and with that came extreme mood swings. He relocated to Phoenix, stayed with a cousin and tried to resume training. His cousin remembers that he was highly temperamental, and he stayed out all night, smoking and drinking heavily. “He was a mess,” Carrera says. Finally, she called Betsy: “This is it. He needs to go someplace.” Terry flew out to Phoenix and found Colt drunk in his room, which he’d never cleaned, and took him back to Southern California.

Colt checked into a rehab facility in Malibu, cleaning himself up enough to draw interest from the CFL and the Arena Football League, but he couldn’t pass a physical. Brain scans showed too much damage from the wreck. Doctors told him he’d never play again—and if the first crash had wracked his body, this assessment was a car crash for his soul.

He tried starting a new life. He moved to rural Oahu and bought a home with a wrap-around deck and views of the Pacific. His backyard was lush with jungle—“like Jurassic Park,” Betsy remembers. But nothing stuck. He blamed Shakti for everything he’d lost, pushing them apart. He abused pain pills and cocaine, but his consistent vices were booze, weed and, especially, nitrous oxide, which he inhaled from small canisters to experience brief states of euphoria. “When I’m having rough times and I want to get away, I hit that and I [disappear] from any problems,” he wrote. “Immediate high is what I’m addicted to.” It gave him “escape, physically and mentally.”

Colt’s legs, ravaged by neuropathy, were deteriorating, and he started using a cane. But, like the Trazodone, he resented the crutch and tried to go without it. He’d lurch one leg forward and drag the other behind, trip and fall, and awkwardly haul himself up. “It hurt to watch,” Betsy says.

In 2017, after one binge in Orange County, Colt collapsed in a hotel hallway and was rushed to the ER, where doctors found blood clots on his spine. Shakti stuck around through nine more months in the hospital, but after his release she’d had enough.

Colt returned to Hawaii and the cycle restarted: physical rehab, addiction treatment, regular meetings with a psychiatrist and a therapist. He even coached some youth football, giving him a sense of purpose, a way to feel useful. “I did well for some time,” he wrote—and in that his family saw hope. When they spoke on the phone, Colt laughed more, made them laugh.

Then the football season ended, “and my purpose diminished,” he wrote.

Colt was trapped in a loop: drinking and drugs followed by arrests and alienation and, ultimately, some catastrophe, the fallout leading to tearful apologies and promises of change; followed by a stretch of sobriety that gave everyone hope; followed by the inevitable relapse that started the whole thing over again.

“Going back to the dark side,” Terry calls it.

“Going down the rabbit hole,” says Betsy. “It’s like he would sabotage himself.”

They let him move back home, but even when Colt appeared clean, he kept them on edge. He made noise at all hours of the night and didn’t clean up after himself. Betsy and Terry were nervous that he’d leave a door open and the pets would get out and they’d be eaten by coyotes. They tried banning him from the house, tried lying to him about when they were around.

A sixth-round pick in 2008, Brennan spent two years in Washington and one with the Raiders, who saw what was coming.

Rafael Suanes/USA Today Sports

“You can’t stop worrying,” Terry says. “You don’t sleep well. You don’t function when you’re under this kind of thing. … It was all so exhausting. One thing after another after another. It was just this constant—”

“—turmoil,” Betsy finishes.

“Turmoil and chaos.”

“He was on this merry-go-round,” Betsy says, “and it was like he kept pulling us onto it with him.”

When anyone tried to pull him off, he’d lash out and accuse them of stealing his money, or of not really loving him. Carrera ignored his calls and texts; his younger sister, Chanel, blocked his number. They knew he wasn’t being himself, but his words, and the strain he put on his parents, hurt. “They did everything, but nothing could ever save him,” says Chanel. “It was so exhausting and stressful.”

“You get so tired, so worn out,” says Terry. “Like: Man, it’s just been this, for years.”

Betsy had to distance herself from it all in order to manage her other responsibilities, namely her job helping run a company that sold time and attendance systems. Terry half-retired from his realtor work, such were the demands of guiding his son. He managed Colt’s bank account and credit card bills and doctor appointments, regularly flying to Hawaii to help out. And Colt whipsawed back and forth between tearfully promising he’d get better and going back down the rabbit hole, to the dark side.

Terry, at one point, looked into setting up a conservatorship, but his lawyer warned against it. The Brennans tried counselors, healers, self-help gurus. Some advised them: Colt has to find rock bottom, lose everything, live under a bridge. But that just didn’t seem right to Terry.

“You just keep thinking: O.K., this is it—this is when the lightbulb is gonna come on,” he says. “You hear about [that] happening for other people, so you just keep doing all you can do.”

Colt, for his part, tried rehab, brain therapy, Alcoholics Anonymous and inpatient programs. He read self-help books and went to a renowned brain-treatment center in Bakersfield. “He was always searching for some way to heal,” says Carrera. “For some way to get better.”

But even Colt seemed to acknowledge the hopelessness of it all, writing in his journal: “I always felt I couldn’t grasp what I needed to do to give my life purpose.”

On went the cycle. A DUI around Christmas in 2019. Multiple stints in Southern California detox facilities and treatment centers. A 60-day inpatient treatment center in Kona. Colt lined up a coaching job, and another at a golf course—but then COVID-19 hit and those jobs disappeared. Reset. By the fall of 2020 he wasn’t speaking to his family. He bounced from apartment to apartment, then to a hostel with a drug dealer, where he was arrested twice in two weeks, for getting in a fight and for disturbing the peace. The incidents made the news in Hawaii and a Facebook group formed, “Ohana For Colt,” with fans reminding the old QB how much he was loved on the islands.

Colt (second from right) with his family: Carrera (second from left), Terry, Chanel and Betsy.

Courtesy of the Brennan family

Finally, that October, Colt wrote a letter to his parents. He was living in a treatment center, reluctantly using a wheelchair, and he was tired of himself. He wanted to go home. “This was a good letter,” Betsy says.

He owned his mistakes, writing: “I have become incredibly impulsive over the years and it’s intense. … I don’t blame you for not wanting me in the house. It’s too nice and I am a disaster.”

He made transparent confessions: “I [have] just become overwhelmed. … so depressed … What’s hard is so much of the pain and hurt I’ve caused. … I’ve written some awful texts.”

He tried to explain himself: “How frustrating life is right now. How hard it is to do the simplest of tasks, like showering. How much it hurts when you have to shop and stand in lines. How embarrassing it is to be in public.”

But he strove to stop being so self-destructive: “There is a lot I want and need to do. … I know I can make you proud again. … I love you guys very much.”

He came back home, living in Orange County hotels and addiction-treatment housing, but it didn’t go well. He got kicked out of a halfway house around Thanksgiving and wrote about the “tuff [sic] hand in life” he’d been dealt, about his “weakness [of] achieving relief through drugs and alcohol,” about how he was “my own worst enemy.”

Colt was the one who wrote that he felt “helpless to help myself”—but really everyone had come to feel that way about him. Says Terry: “I think even the shrinks were baffled by him.”

In January, Colt found Tree House Recovery, just 15 minutes from his parents’ home. To be admitted to the ultra-exclusive drug- and alcohol-rehab center he had to arrive sober and then interview with the program’s founder and director, Justin McMillen, among other staffers. Once he was in, Colt moved to a group home for five months, every day of which he visited Tree House’s main facility, a sprawling building laid out around a dazzling gym that smells like sweat and saltwater.

And his stay was like nothing Colt had experienced before, at any of his treatment programs. Ryan Bain, a former D-I football player turned mental health counselor, also created Tree House’s foundational ESM fitness therapy (from the Latin exercitium semita medela, meaning, roughly, “exercise as a pathway to healing”). A typical morning would begin with a 5:30 gym workout; on other days Colt might put on a wetsuit and go to the beach, where he and a team of Tree House clients piloted large inflatable rafts through the waves.

Kevin Burns, a construction worker who entered the program a week after Colt, remembers how Brennan—having packed on weight, and still dealing with his damaged legs—struggled with the workouts. “It was rough,” says Burns. “Every step [looked] like he was breaking his ankle.” But Colt kept going, and he motivated others, joking: “Just wait until I get a brace!”

With the Tree House guys, Colt’s best side came out, and he had a way of bringing out the best in them, too. “He would bring everyone else around him up,” remembers Landon McNamara, who finished the Tree House program a year before Colt and was visiting during Colt’s stay. “He’s just this huge-loving person.”

Each day at Tree House was built around the idea that exercise primes the brain for learning, and so after pushing his body, Colt and his new friends would be schooled in psychology, biology and neuroscience, learning about how the brain becomes wired for addiction—and how it can be rewired. In class Colt was “like a sponge,” says Burns. “You could tell him something, and the next day he would recite it word for word.”

Colt learned that he was just a human being with an organ suffering a medical condition. This contradicted what so many of Tree House’s clients had thought all their lives. “[Addiction] is such a misunderstood thing,” says McNamara. “I grew up [being told], ‘You’re just f—ing weak.’”

Instead, Colt learned that addiction, really, comes down to a tug-of-war between the prefrontal cortex, which governs rational decision-making and impulse control; and the limbic system, which controls emotions and impulses. A healthy brain needs a tension between the two—it needs to know when one should take over for the other. And while all humans can struggle to find that proper balance, addicts are people who just struggle more. Colt was taught that he’d been born with a brain more vulnerable to addiction in large part because he had a strong limbic system—all his emotions, he felt deeply.

Anyone, Colt learned at Tree House, can become addicted to anything. Drugs and alcohol. Social media. Video games. Even emotions—anger, sadness, pain. But drugs and alcohol are especially good at helping the brain cope with pain—and in time Colt had come to feel that these were the only things that could help him deal with his own personal afflictions.

In Hawaii, says Bess, Brennan was treated “like a rockstar.”

Jordan Murph/Icon Sport Media/Getty Images

“Humans are built to bond; our survival is dependent on it,” says McMillen, the Tree House founder. “And if we can’t find that, we will absolutely attach to whatever gives us that feeling.”

Tree House’s classes teach that when that happens—when addiction sets in—the prefrontal cortex underfunctions and the limbic system overfunctions, destroying the network of neurons and synapses connecting the two. The brain rewires itself to seek drugs like it might otherwise seek oxygen, and because of that, it treats any threat to that drug as a danger. Treatment, therapy, sobriety, loved ones offering help—these all become mortal threats. “Your brain is malfunctioning,” says McNamara.

The way McNamara was taught to understand it, addiction is like an invisible cancer of the mind. “Are you gonna get pissed off at somebody,” he asks, “for having a f—ing tumor?”

Colt was trained to see his own self-sabotaging behavior as having a scientific explanation: Post-Acute Withdrawal Syndrome (PAWS). “All of a sudden, something snaps in your head,” says Burns. “This place taught me: That’s normal. You’re gonna have those feelings. [We use] certain therapy methods to work through it, to keep you from doing what your brain wants you to do.”

These lessons all gave Colt a sense of peace. His brain had a wiring malfunction, and he could repair it. He saw his problem, and he saw his solution. The therapies and counseling that Tree House offered—exercise, education, writing, relationships, life planning—could provide the same neurochemicals that drugs provided to his brain. He just needed time to adjust. So he trained and learned and wrote in his journal. He wrote about football, Papa, Colorado, Shakti, the car crash, how lost he felt, how much he’d screwed up and how much he still wanted to do with his life.

Those close to Colt believe it was working. “The light was back in his eyes,” says Terry. As Colt continued through the Tree House program, his parents welcomed him back home for visits. Carrera and Chanel started talking with him again. Chanel’s three-year-old daughter, Bentley, finally got to know the better side of “Uncle Colty.”

“He was Colt again. He was back,” says Betsy. “We finally stopped worrying about him.”

Colt started quoting a line from Kung Fu Panda, like it was his mantra: “Yesterday is history, tomorrow’s a mystery, and today is a gift—and that’s why they call it the present.”

He finally got his brace, and while it didn’t fix everything, it helped enough that when the Tree House gang went to play football at the park, Colt would quarterback both teams.

In May the Brennans celebrated Mother’s Day early, on a Wednesday, so that Betsy, Terry and Chanel could go to Mexico. Colt gave Betsy a card thanking her for her love, writing: “I’m finally starting to find [my] way.”

On Friday, he and Burns took a leadership class together at Tree House as they prepared for their graduation. They had plans to get an apartment together and to open their own Tree House center in Hawaii, where Colt would coach youth football again. “Despite being 37, I truly feel I can finally see … a life filled with purpose and happiness,” he wrote in his journal. “Right now I got a lot of work, but I think I’m ready.”

Sometime that Saturday, Colt went to his parents’ home and started drinking and using nitrous. Nothing specific seemed to trigger the relapse, although those close to him have theories. “You remember The Shawshank Redemption?” Terry asks, referencing a character in that movie, Brooks, who after being released from prison finds himself so scared by freedom that he hangs himself. “I think that’s kinda the mentality people like Colt get into. They just say: This is my lot in life. This is how it’s gonna be.”

McNamara thinks it could be simpler than that: “Somebody can be in a place where they really, really want to be doing better, and they’re really committed—and they’ll still slip up,” he says. “It’s irritating. It pisses everyone off. But at the end of the day, the person who’s hurting the most is the one who’s actually going through it.”

That’s when the self-doubt starts, he explains. Can people believe in me again? Will they ever trust me? Can I even forgive myself? Trust myself?

“The guilt and the shame drive people back,” McNamara says. “And that is addiction. No one wants to hurt the ones they love.”

Often, the knowledge that your relapse will hurt the people you love drives you deeper back into addiction, the only place where you seem to find relief from the pain. That’s the danger that comes with getting sober, he says. A dark before the dawn. Because it hurts to see the past clearly. “Once you get into a healthy mindstate, that’s when it gets the hardest,” he says. “You’re like: S—, I did all of this?”

Still, Colt didn’t have to die.

After returning home to find his son drunk and high that Sunday night, Terry drove Colt away without knowing where to go or what to do. Colt asked to stop at In-N-Out, and Terry said O.K. He got his 3×3 with fries and a Coke.

Terry called Tree House and spoke to McMillen, who said that Colt needed to go through detox. Colt had taken that route before at Hoag Hospital, in Newport Beach, so Terry pointed the car in that direction.

Before detox, though, Colt had to pass through the ER at Hoag. Terry and some nurses helped Colt into a wheelchair, and the nurses checked his vitals.

Colt’s hijacked brain, meanwhile, went into attack mode, angry at this threat to its intoxication. He said he was fine, that he didn’t know why they were doing this to him, that Terry was an idiot, that they were all idiots, that everyone needed to leave him alone, that he didn’t belong there.

Terry had heard it all before. But he also felt like his presence was exacerbating the situation, so after an hour he made sure the nurses had his information and he went home, leaving his son in the hospital’s hands.

An hour later, around 8 p.m., a nurse from Hoag called Terry. Detox was full, so they were releasing Colt.

“Wait a minute,” Terry says he shot back. “You can’t release Colt. He’s not in any shape to be released.”

The nurse said she’d talk to a doctor and call him back. But Terry says that didn’t happen.

Instead, around 9 p.m., Betsy and Terry—exhausted from their travel and emotionally drained—assumed that Hoag had kept Colt after all, and they fell asleep. The phone didn’t ring again until 7:30 the next morning. On the other line, a nurse from Hoag was explaining how Colt had been unconscious when the paramedics brought him in.

“Paramedics?” Terry asked. “What are you talking about, ‘paramedics’?”

This is what Terry says he was told: The hospital released Colt at 1 a.m. He’d demanded it. He was given a bus pass and the address for a detox facility one county away. And instead he went 10 minutes down the road to the Sandpiper Motel, a run-down, two-story joint that looks like a place where lost souls might stop to think things over one last time on their way out. Three hours later, paramedics responded to a 911 call and found Colt unconscious and not breathing, from an apparent drug overdose. They administered Narcan, an anti-opioid agent, but couldn’t revive him.

Now, the nurse on the other end of the phone told Terry, Colt was in a coma at the ICU, being kept alive with a ventilator and an IV.

After he and Betsy came home to find Colt passed out in May, Terry (left) found himself at a loss.

Courtesy of the Brennan family

Betsy and Terry rushed to the hospital. Chanel arrived soon after, and Carrera flew in from Aspen. The Brennans aren’t a religious family, but they prayed. They talked to Colt while the electrodes strapped to his skull searched for signs of activity in his brain. Chanel played Bob Marley on her phone and put it on a pillow by her brother’s ear. They bought a Hawaiian lei from the gift shop and laid it on his chest. They wrapped a blanket around his cold feet.

That night doctors told the family that they’d done all they could. Colt’s brain was dead. Betsy remembers the word they used: irreversible. His organs would shut down without life support. Facing the inevitable, the family decided together not to make Colt linger.

A nurse injected Colt with morphine—one final drug—to prevent any more pain, and then everything keeping him alive was removed. His breathing slowed until it stopped a few minutes after midnight.

In the aftermath of Colt Brennan’s death, his family was wracked by questions. Questions about why Hoag had released him in the middle of the night, in his condition. About how he got to the Sandpiper. About what he consumed when he got there.

Police offered no answers. (California’s Good Samaritan Law provides prosecutorial immunity to people who call 911 for help with someone suffering a drug overdose.) In fact, authorities had their own questions. In the weeks after Colt’s death, agents from the Department of Justice visited the Brennans’ home because Colt’s condition suggested that he’d consumed fentanyl, a dangerous synthetic opioid—10 times stronger than heroin—that dealers often use to cut other narcotics because it is cheap and easy to produce, leading to a surge in accidental drug overdoses in recent years. Terry remembers the agents saying that this was “going on all over the place” and that the lack of control authorities had over the situation was scary.

Months after that visit, in September, autopsy results provided a first, unsatisfying answer. Colt had died from the “combined toxic effects” of ethanol (likely in alcohol), methamphetamines (troubling as it was, Terry knew Colt had occasionally consumed meth), amphetamines (possibly from Adderall, which they think Colt sometimes used) and fentanyl.

It was the fentanyl that shook Terry, who can’t bring himself to believe that his son consumed the drug intentionally. “It really bothers me,” he says. “It really confuses me.” Colt said he knew people who took fentanyl, and he’d tell his dad, “When people take that stuff, it’s really bad.” Terry says, “He never did any of that kind of stuff.”

As a junior, Brennan set a single-season record with 58 passing TDs. As a senior, he took Hawaii to the Sugar Bowl, against Georgia.

Bob Rosato/Sports Illustrated

But what really frustrates Terry, what makes him angry when he’s tired of feeling pain, is the fact that Colt, after he showed up at Hoag, was released at all. “[Colt was] an adult, which means you gotta let him go—I understand how the law works,” Terry says. “But I would’ve gone and picked him up [if they’d called]. I wouldn’t have liked it. But I would’ve gotten him.”

“They should be ashamed,” McMillen says. “If he was not a drug addict, I guarantee you they wouldn’t have released him.” (A Hoag spokesperson did not comment for SI.)

Anyone who closely encounters an addict is left with an onerous choice: invest massive amounts of time and energy trying to save this person; or turn them away, which everyone—not just Hoag—did to Colt at some point, in their own way, all for reasons that are both justifiable and gutting. In some ways, the difficulty of a drug’s hold on a person is matched by the powerlessness it heaps on those around them.

No one wants to hurt the ones they love.

One day in late July, in the living room of the Brennans’ home, as Betsy and Terry clean up after lunch, Chanel plays with Bentley. Behind them, sliding glass doors open to a patio with a sweeping view of Orange County below. A photo on the wall captures Colt with his Tree House friends, at the beach in their wetsuits, arms linked together as they walk into the water, shot in silhouette from behind.

Bentley says she misses Uncle Colty. Everyone visited him the other day at Pacific View Memorial Park, in Corona Del Mar, where the family buried some of his ashes, next to Papa’s. They spread some more in the ocean off the shore in front of a family beach house an hour south in Oceanside, and the rest sit in a box in a shrine on a shelf in the Brennans’ foyer, waiting to be scattered in the waves off Oahu in the spring.

Chanel has been wrestling with how she handled things with her brother. “I feel guilty that I wasn’t more empathetic,” she says. “I always believed [addiction] is a disease, but then—I don’t know why—when it came to my brother, I became frustrated with him.”

She has a tattoo on her wrist now, in Colt’s handwriting, that reads LOVE YOU SO MUCH. At one point she posted a picture of Colt on Instagram, writing: “There are so many things I wish I did differently … when you were still here. The guilt is real and the sadness is never-ending. I hope your story … can help others like you. I hope our openness and honesty as a family can help other families who are navigating the rough road of addiction and mental illness with a loved one know they are not alone. And I hope the more we talk about it, the better outcomes there will be.”

The Brennans donated Colt’s brain to CTE Center at Boston University, and they set up a foundation, partly to support people with addictions. UH retired Colt’s jersey in October. Betsy and Chanel, in the meantime, sought more proactive ways to heal themselves, and to find answers. One day, they spent an hour together on the phone with a medium.

Betsy says the call helped—Terry rolls his eyes—and replays a recording. The medium tells them that Colt says his death was an accidental overdose, that he didn’t mean to take the fentanyl, that he’s sorry, that none of this is their fault, and that he loves them. “He needs you guys to know that there was absolutely nothing you could’ve done differently that could’ve changed this outcome—O.K.?” the medium says. “When we leave the planet early in our life, it’s because we graduated. … That was why he left as early as he did.”

The medium says that Colt is happy and at peace, somewhere unimaginably beautiful. “Nobody in their right mind ever wants to come back from there once they’ve been,” she says. He is there with family. With Papa.

• The Discovery, Mystery and Controversy of the Original Horns

• Karl Anthony Towns Opens Up About His Season of Grief

• Inside the Quest To Prolong Athletic Mortality

[ad_2]

Source link