[ad_1]

As a player, my mantra was: practice makes perfect. It’s the same now I’m a coach, but I’m not looking for the next Dennis Bergkamp. I want to improve players and it wouldn’t be a challenge to coach my younger self.

By that I mean I was a player who could solve problems myself – I didn’t really need a manager or coach for that. I did my own thing but I was always professional about it. I was respectful enough to the manager to play in his philosophy, in his system. None of them had to ask me to change the way I played or trained.

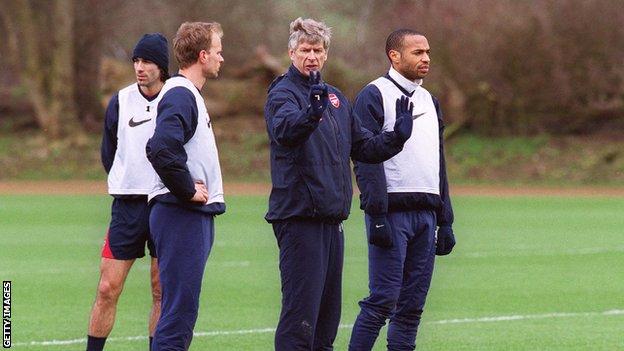

Of course, with some of them – Johan Cruyff or Arsene Wenger, for instance – it was my philosophy as well, and that helped. But when I work with players now, I always prefer a challenge – like someone who is upset with me for any reason or, technically or tactically, doesn’t know what to do. I feel that I can help.

I’ve not worked full-time since leaving Ajax in 2017 and I am not actively looking for a job in football at the moment. But, more and more, I am thinking about getting back on the training pitch again, because that is what I love the most.

Whatever I do next, though, I don’t want to be a head coach. It’s not my ambition and I like my freedom too much. I like to spend time with my family and have a life outside football, and I don’t think you can be a fully committed manager if you want to play golf sometimes as well.

Seriously, though, I know certain clubs work with strikers’ coaches, just like the old goalkeeper specialists who came in two or three times a week and as soon as the session was finished they were gone. But, for me, it would be too restrictive to be limited to that side of it. If someone is not doing well, I’d want to talk about the rest of his game – whether it be something tactical or a personal issue.

What I have in mind is a role that worked for me at Ajax, which was a lot like the one I had as a player – a little bit in between the lines. I wasn’t really a striker or a midfielder, but in between.

That’s how I see myself as a coach as well. I like to be involved with the first team but I think my power, my strength, is to bring players from the youth to the first team.

Sometimes the youth team and first team can be like two islands. What I am talking about doing is like a bridging role between them, but I realise I’d have to have results as well. I wouldn’t be working for the sake of it; just to go to work and come home again. I’d like a challenge and to be really responsible for developing players and bringing them through.

I like that pressure. I had success doing it at Ajax – where I wasn’t an assistant or a second assistant, I was on the training pitch – and I am a big believer that it would work with the other big clubs in Europe as well. I am actually surprised more of them don’t do it already. You can see a lot of them have got strong youth systems and everything good is in place. It’s just about what happens next.

It is such a big advantage if you can develop your own players because, unlike most players you buy, they don’t have to adjust to a new club or new country. They are already comfortable and they are available whenever you need them.

Maybe in the future there will be a rule for it, like the ‘six and five’ rule that Fifa once discussed, where you had to have five homegrown players in your team. I guess when you have a lot of money, though, the first option is always to buy – and buy big – rather than invest in the youth, which is a shame.

That’s one of the differences between being a player and a coach. My philosophy as a coach is based on my whole career and my life, but the decisions I wanted to be made when I was at Arsenal were more based on me wanting success. If we were missing something in the team, I would always hope that would change quickly.

Even then, though, we did not have the big money to go out and sign really expensive players and I guess it’s the same for Arsenal now. They cannot just go out and sign big names in every position, but they have a lot of talent coming through. They have to be inventive if they want success, but it looks like the club is heading upwards again and I think if the fans can see progress, they don’t mind having to wait.

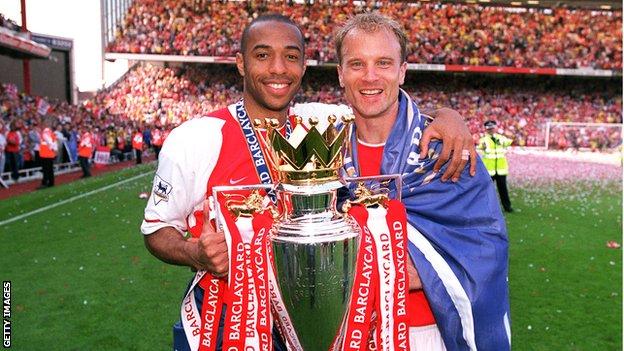

They will need that patience too. Whether it’s Arsenal or anyone else, if you don’t spend big money then it takes time to build something. When you finish eighth, like they did last season, it is a big challenge to get players of the level of Thierry Henry or Robert Pires. You have to try something different, rely a little more on the manager, his philosophy and the playing style – and, yes, build yourself up.

Part of that is developing the players you have already got. There are a lot of managers who think they can change players by 40% or 50%, but I don’t believe in that. I think, even with youth players, you can change them only by a small percentage – but that is enough, especially in top football.

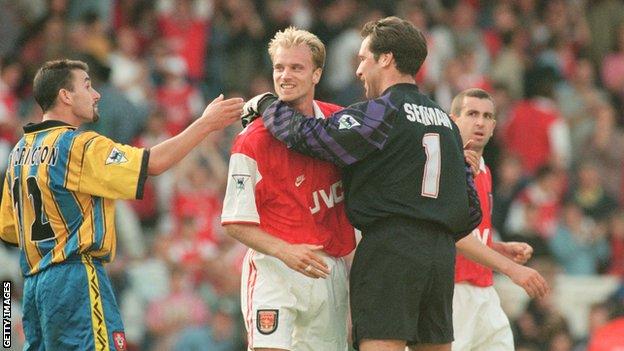

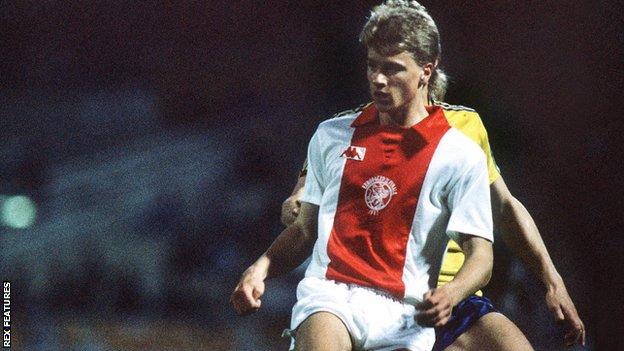

Most people look at players and they say ‘oh, what a good technique’, or ‘he works very hard’. But there is a lot more to it than that – I learned that a long time ago, when I was just a boy at Ajax, working under Cruyff. He demanded a lot and I feel it’s important that I teach the same lessons now.

At Ajax we understood that a player is built out of four parts – a tactical side, a technical side, a physical side and a mental side. If you want to be a professional footballer, you need all of those four parts working at a high level, otherwise you won’t make it.

You can build a young player if you have all this in mind. In your training sessions you can put all of these things in. So, for example, if a player has got a problem with referees in games, then in training you make sure everyone can foul him and he doesn’t get a free-kick. Make him deal with it.

All of that happened with me. The idea from Cruyff was to toughen me up. As a teenager, I once got demoted to a lower team at Ajax, to provoke a reaction from me. They put me in the outside of the wall at free-kicks so I had to communicate with the goalkeeper and, when I played out wide, they put me in other positions that were affected by where I usually played. All of that stuff.

It doesn’t have to be somewhere a player is obviously lacking, but it can be somewhere that you want to test them. Sometimes you just want the player to have to think for himself – but can they do it?

These days, from a very young age, football coaching at every level is far more structured than it was when I grew up. I don’t know exactly how it is in England now but here in the Netherlands everything is arranged for children – there are artificial pitches everywhere for their coaching and all the sessions are planned.

They are taught more nowadays and it seems that the creativity has gone a little bit. Sometimes when I watch youth football, you have what I call PlayStation coaches – they have got the controls and the players are just doing what they say, not thinking for themselves.

The way you get good players is if they’re inventive, but all the way to the age of 18 they’re not getting the chance. The time they have with their coaches is sometimes the only time they play. I think if you look at the generation now, and compare it to my youth, they miss out on about 15-20 hours of playing football a week. That is a lot and you have to try to bring that creativity to them in a different way, so they understand how important it is.

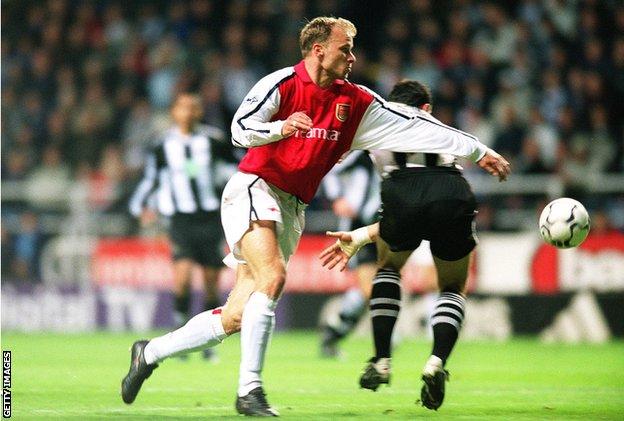

For my most famous moments as a player, I needed footwork, balance and skill. They are all things you can learn; they are the tools you need. But I also had to be inventive to know when to use them, and I had to work that out for myself.

I learned my touch and my technique by kicking a ball against a wall hundreds of times in a row, controlling it time and time again, and from playing games for hours every night – in the streets, on gravel, wherever. Even at Ajax we might have a passing exercise and a finishing exercise, then we played a match.

That was my generation and the generations before. We would just go outside with the ball and mess around with it. Now there are so many other things in life – mobile phones, video games and stuff – that the kids don’t get out as much.

That’s not the only difference with the modern game. It’s 14 years since I stopped playing and football has changed a lot. Off the pitch, everything seems bigger – the money, the coverage, the social media. On the pitch, it looks a bit quicker than in my day.

But some things are the same – you can see teams like Liverpool and Manchester City have a certain philosophy and are successful with it, and the other sides are trying to catch up.

One of the biggest things to have changed is the use of statistics and how they are interpreted to show if a player is good or not. Again, it’s an area where things are evolving all the time.

When I played, the stats were basic and I didn’t pay much attention to them for a long time. I had a discussion with Arsene once about them, and he said to me, because I was in my 30s: ‘I can see from your stats that your level is dropping after 60 or 70 minutes, that’s why I take you off most of the time.’

I said: ‘OK, boss, but your statistics don’t show that even at 80% I can make the important pass before the goal.’ I always called it the pre-assist – the moment that splits the defence and leads to a goal, even if it isn’t the final pass.

Of course, even then you could take something out of the numbers – mostly physical data about the distance covered in a game and things like that – but ideally you have to combine that side of it with the intelligent, technical side and that still seems very difficult, even though things have progressed.

With some players, their numbers do not do them justice. For example, Liverpool’s Roberto Firmino is a player now who you have to see yourself to appreciate what he brings to his team. David Silva was another when he was at Manchester City, with his passing rate and how he set the tempo for them to play.

Stats are another window into the game, but it is not the only way. I still think your eyes make the definite decision on certain things, and then the stats can help you – maybe to prove that you see it right. One day, perhaps, all the stats you need will be there, but for now I know which players I love watching.

In my house, there was quite a sigh of relief that Kevin de Bruyne won the Professional Footballers’ Association Player of the Year award for last season. He’s been excellent for many years without getting the individual recognition he deserves. Now he has it.

I really enjoy watching De Bruyne and have done for a long time. I remember the first time I saw him, when I was with Ajax and we played Wolfsburg in a pre-season friendly. He came on at half-time and he was so confident and comfortable on the ball and his vision was all over the pitch. He could see everything and everywhere, even then. That is something I value highly, of course.

De Bruyne drives his team forward and he has excellent technique too. If you do what I said earlier – practise and practise from a young age – then what he does becomes natural to you. Sometimes in Premier League games I see players who have to look at the ball for every touch.

The good players, the best players, always know where the ball is. They don’t have to look at it – they see the space instead, which is the most important thing in football. I think they can do that because, in their youth, they played a lot with the ball. It worked for me and it would be the advice I give to every young player now: practise, practise, practise.

I always thought I could improve, and you can too. As a coach, I have not stopped learning either – I am forever picking up new ideas, observing and seeing things that can make a difference for me or for someone else.

Dennis Bergkamp was speaking to BBC Sport’s Chris Bevan.

[ad_2]

Source link