[ad_1]

The moonshot implantable chip for the brain was unveiled on Friday, but rather than present a human test subject, he presented a pig named Gertrude.

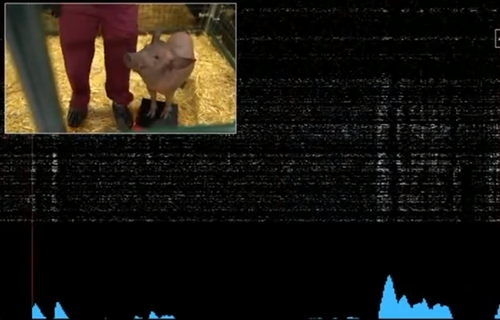

In a live-streamed event that began characteristically late, Mr Musk unveiled three not-so-little pigs: one that did not have an implant from his brain-computer interface company, Neuralink; one that had been implanted in the past; and Gertrude, who currently has a prototype of the device.

Gertrude shuffled around her pen, sniffing the ground and eating, while loud beeps and blips filled the air and a display showed real-time spikes in her brain activity.

Mr Musk explained that Gertrude had the implant inserted in her head two months before, and that it connected to neurons in her snout.

When she touched something with her snout, it sent out neural spikes that were detected by the more than 1000 electrodes in the implant.

Why show pigs when you’re developing a product aimed at humans?

“Pigs are actually quite similar to people. If we’re going to figure out things for people, then pigs are a good choice,” Mr Musk explained during a question-and-answer session after the pig reveal.

“If the device is lasting in the pig, as it lasted in there for two months and going strong, then that’s a good sign the device is robust for people.”

The presentation came more than a year after Musk first introduced his plan for a new kind of implantable computer chip.

Last July, he sketched out a vision of a computer chip connected to extremely slim wires with electrodes on them, which would be embedded in a person’s brain by a surgical robot.

The implant would connect wirelessly to a small, behind-the-ear receiver that could communicate with a computer.

Mr Musk says he hopes the implant could one day help quadriplegics control smartphones, and perhaps even endow users with a sort of telepathy.

Like existing brain-machine interfaces, it would collect electrical signals sent out by the brain and interpret them as actions.

He said the company scrapped the idea for a behind-the-ear receiver in favour of a fully embedded implant about the size of a coin that would be placed below the skull — a plan that sounds more invasive than what Mr Musk unveiled last summer.

He showed off a prototype of this so-called Link, which he said would include many of the sensors in your smartphone, such as a six-axis interial measurement unit and temperature and pressure sensors.

The device uses Bluetooth Low Energy to communicate with a computer.

The idea of a brain-machine interface is not new; scientists have been working on them for decades, and they have been implanted and tested in animals such as monkeys, as well as in humans.

There are some deep-brain stimulation devices approved by the US Food and Drug Administration that are meant for, among other things, controlling tremors in people with Parkinson’s disease.

And several tech companies have worked on their own methods for connecting the brain to computers.

San Francisco-based Synchron makes a wireless device that’s placed using the blood vessels – averting the need for surgery to get the device into the brain.

It announced it got breakthrough designation from the FDA this week. And it’s begun testing the device in people.

Yet these efforts tend to be confined to labs for a number of reasons: they’re expensive, bulky, require training (of both the user and the computer), and, when it comes to an under-the-skull implant, the person outfitted with it generally must be physically tethered to a computer for it to work.

They also tend to be limited to painstakingly slow applications, such as typing.

The surgical procedure required to embed these devices in the brain can be complicated, too — these days, the skull is typically cut open, the brain is exposed, chips are installed, connectors are mounted to the skull, and the head is stitched up.

Mr Musk claimed last year that Neuralink’s robot would instead be able to implant wires under a person’s skull as threads, bypassing blood vessels and causing “minimal trauma”.

On Twitter earlier this week, in response to a question about how close the Neuralink procedure is to the simplicity of LASIK eye surgery — a comparison Mr Musk has made in the past — he predicted that Neuralink “could get pretty close in a few years”.

It’s worth noting that Mr Musk, who is also CEO of Tesla and SpaceX, has a history of making bold and outlandish technological predictions that don’t always come to pass: he planned, for instance, to send space tourists around the moon in 2018, which hasn’t yet happened.

Neuralink, which was founded in 2016, has previously tested a wired version of its implant in rats (and Mr Musk indicated it has enabled a monkey to control a computer with its brain, as well).

Previously, Mr Musk said in July 2019 that human trials could start by the end of 2020, though the company didn’t then have approval from the FDA for such a study.

[ad_2]

Source link