[ad_1]

Fritz Pollard Jr suffered from Alzheimer’s during the final years of his life, but just before he died there was a moment of clarity.

With his last words, spoken to his family in 2003, he said: “Don’t forget your quest.”

That quest had also been his own – to get his father into the US Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Some 27 years before Jackie Robinson broke the colour barrier in baseball, Fritz Pollard was the best player for the first NFL champions in 1920.

In a decade during which hundreds of African-Americans were still being lynched, he was playing a ‘white man’s game’ when the NFL was in its brutal infancy.

In 1921, Pollard became the league’s first black coach and in 1923 its first black quarterback. Yet after he retired, the doors he forced open were slammed shut by a ‘gentleman’s agreement’ that saw African-Americans banned from 1934 until 1946.

By the time the NFL’s second black head coach was appointed in 1989, Pollard, who died in 1986, had long been written out of the history books.

But his family’s quest finally came to fruition in 2005 when – two years after his son’s death – Pollard was inducted into the Hall of Fame.

Now, the power of his legacy is growing through an organisation that bears his name. The Fritz Pollard Alliance was in 2016 one of the first to support Colin Kaepernick, another black quarterback who has had to wait for the significance of his deeds to be acknowledged by his sport.

And yet, still very few NFL fans have even heard of Pollard. His is a story for too long left untold.

The Pollards were well known in Rogers Park, a suburb on the north side of Chicago. Pollard’s Barber Shop was a popular neighbourhood hang-out and the Pollard boys played football for hours in the local park. They were the suburb’s only black family.

Coming out of the Reconstruction era which followed the American Civil War, the Pollards wanted to live free from the racial oppression of segregation laws in the south and had moved from Oklahoma in 1886.

Mother Amanda was a respected seamstress while father John was a successful businessman. After escaping slavery, he had fought for the Union during the Civil War.

Born Frederick Douglass Pollard in 1894 – after the abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass – his nickname Fritz reflected Rogers Park’s predominantly German make-up.

During high school Pollard was actually a better baseball player, but he knew he wouldn’t be able to progress. At that time, black players were banned from the sport. American football was different.

His three older brothers all played the game and felt black players could do well – if they adhered to an unwritten code of conduct. They taught Fritz that he could never retaliate, despite the provocation he was sure to face.

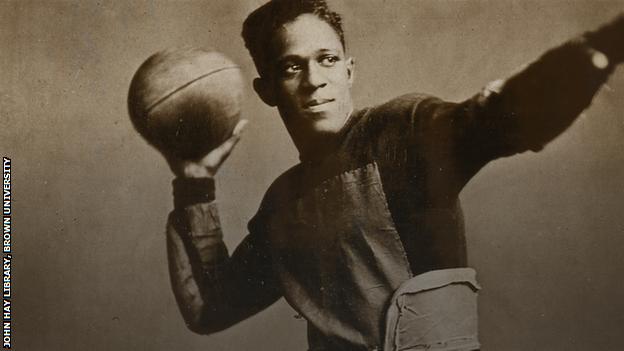

Fritz was gifted with speed and elusiveness but he was small. When he began playing football aged 15 in 1909, he measured 4ft 11ins and weighed 89 pounds. His brothers decided they had to toughen him up. They knew he’d be targeted because of his size and skin colour.

All eight of the Pollard children graduated from high school and excelled at athletics or music. The family had prospered. Their move north had paid off. Fritz, the standout achiever, earned a Rockefeller Scholarship at Brown University, an Ivy League school in Providence, Rhode Island, on the United States’ east coast.

Everything he learnt from his brothers was about to be put to the test.

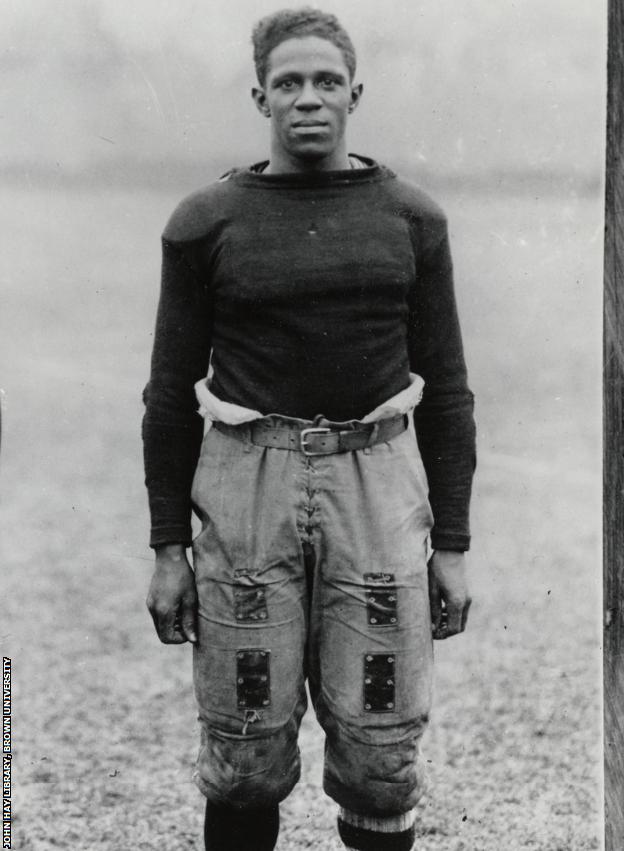

Pollard was one of only two African-Americans at Brown in 1915 and the first to live on campus. When he showed up for football practice that September, none of the players wanted him on the team.

One of his team-mates, Irving Fraser, later told Pollard’s biographer Jay Berry: “When he was tackled, they’d all pile on him and see if they could make him quit. But Fritz would get up laughing and smiling every time. I never saw him angry.”

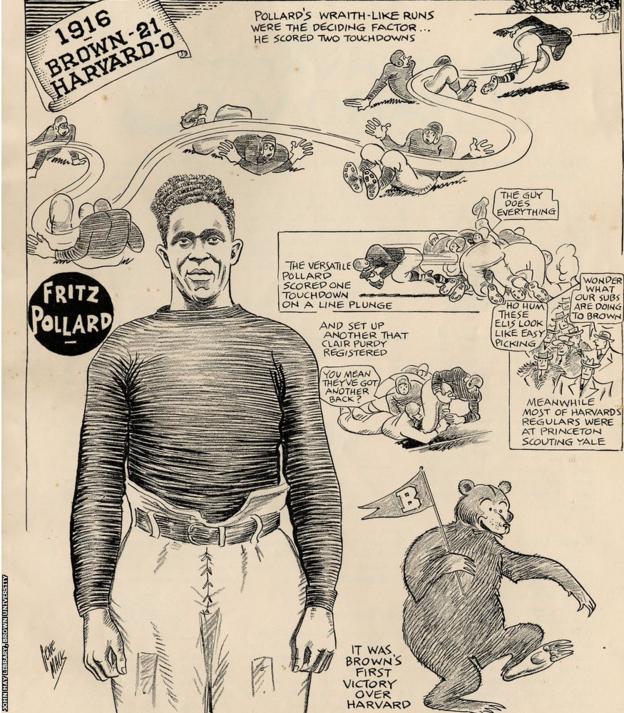

‘Bloody Wednesdays’ were the scrimmages where reserve players could challenge starters for a spot on the team. When an opposing linebacker greeted Pollard with a deeply offensive racial slur, he responded by waltzing past him and into the end zone. Pollard asked to run the play twice more and scored two more touchdowns.

“We better let him play,” the linebacker told the coach.

Aged 21, Pollard was only 5ft 8ins – small for football, even then. But the fleet-footed running back quickly became the team’s star player, dubbed ‘the human torpedo’ because he ran so low to the turf. In his freshman year, he was the only black player in the Ivy League and Brown’s win over Yale saw them earn an invite to the Rose Bowl in January 1916.

On the train out west to Los Angeles, even black porters refused to wait on him. The same players that shunned Pollard four months earlier were now bringing him food. They also threatened not to play when he was denied a room in LA. Eventually the hotel relented.

For the game at Yale, Pollard had been smuggled into the stadium via a separate gate. It was one of many measures he’d take to avoid being targeted, verbally and physically, by fans and players alike, across the game’s heartland of the American Northeast and Midwest.

Imagine NFL stars of today like Patrick Mahomes and Lamar Jackson having to arrive moments before kick-off and being driven on to the field. Sometimes Pollard’s team stayed in centre-field at half-time rather than run the gauntlet of going into the locker room.

The Yale supporters also turned ‘Bye Bye Blackbird’, a popular song of the day, into a racially abusive anthem. Rival fans would taunt Pollard with it throughout his career. As he recalled the song in his final interview with Berry before his death in 1986, tears rolled down his cheek.

But in the 1916 season, Brown beat Yale and Harvard on consecutive weekends. It was the first time a team had beaten them both in the same season, and Pollard won each game almost single-handedly. Brown finished with an 8-1 record, with their star player selected in the All-America team.

Pollard left a lasting impression in Providence. There are three awards in his name at Brown and in the 1970s, when his grandson Fritz III played football there, a local shop owner refused to take his money and said: “My father took me to see your grandfather play. It was the best game I’d ever seen.”

Academic difficulties meant Pollard’s college career was cut short. In 1917 he enlisted in the army, serving as a physical director in Maryland while coaching at the all-black Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. He feared he had squandered any chance of playing professional football.

Then came a telegram that changed everything.

“They threw rocks at me and called me all kinds of names. But I was there to play football. I had to duck the rocks and the fellas trying to hurt me.”

The US summer of 1919 was known as the Red Summer. Race riots took place across the country. Hundreds of black people were killed by white supremacists. Some of the worst violence took place in Pollard’s home town of Chicago.

Pollard himself was now in the factory town of Akron, Ohio. The new owner of a team there had got in touch with him. His professional career was finally about to begin.

At his first game, he had to get dressed in the owner’s cigar shop and was abused by his own team’s fans. In his second, he faced future Hall of Famer Jim Thorpe.

As a native American, Thorpe had battled racial prejudice to become a multi-sport star, winning golds in decathlon and pentathlon at the 1912 Olympics. Yet he welcomed Pollard with a highly abusive racial slur, saying he was going to kill him. Pollard told him: “You’ll find me down there in your end zone.”

Pollard and Thorpe were pro football’s highest-paid players, the main attractions. Still, many were motivated to see them by the opportunity for abuse.

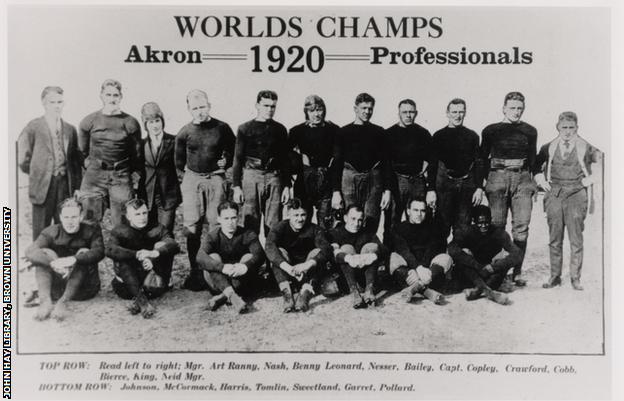

The following 1920 season was the first for the American Professional Football Association – renamed the NFL in 1922 – and the Akron Pros went undefeated, outscoring their opponents 151-7.

Pollard was the only Akron player named in the All-Pro side, but when the team received their championship trophy, he wasn’t invited. He was honoured instead at a separate banquet held by a local black business association.

In 1921, Pollard was made player-coach and finished as the league’s top scorer. He could do everything – he played on offence and defence. As well as being a running back, he was a defensive back, receiver, kicker, punt returner and kick-off returner.

Then in November 1923, after switching teams, he played an entire game at quarterback for the Hammond Pros. It would be almost half a century until the NFL next had a black starting quarterback.

In his seven-year pro career, Pollard played for four NFL teams plus two in rival leagues in Pennsylvania. Segregation laws had been abolished in the northern states, but with many southerners migrating for work in the rubber factories of Ohio and the coal mines of Pennsylvania, he continued to experience racial discrimination almost everywhere he played. As his team returned from one game in Gilberton, the train’s windows were shot out.

“You couldn’t eat in the restaurants or stay in the hotels,” Pollard told the New York Times in 1978.

“Hammond and Milwaukee were bad, but never as bad as Akron. They had some prejudiced people there. The opposing teams gave me hell too.”

Teams would take kick-offs short, so that Pollard could be gang-tackled as soon as he received the ball. If the field was a quagmire, his face would be held in the water.

But he combated such treatment with tricks he learned from his brothers. When returning kick-offs, he often dived to the floor, leaving the tacklers to collide with each other, before getting back to his feet to continue running. When he was tackled, he’d flip on to his back and pedal his feet in the air to stop opponents piling on to him.

Pollard ended his playing career in 1926, aged 32. He continued to promote the integration of more black players. He coached and managed all-black teams in exhibition games, giving them a chance to showcase their talent.

By February 1933, there had been 13 black players in the NFL. Then a fateful meeting took place in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Fritz III says his grandfather felt there were two reasons why he wasn’t voted into the Hall of Fame during his lifetime: George Halas and George Preston Marshall.

Halas was involved with the Chicago Bears from their creation in 1920 until his death in 1983, first as a player, then coach and team owner.

Marshall was an avowed segregationist who owned the Washington football franchise from its inception in 1932 to his death in 1969. He called the team Redskins in 1933, a racial slur that was only dropped in July this year amid mounting pressure. A memorial for Marshall outside Washington’s stadium was removed in June, along with all other references to him, after it was spray-painted with the words “change the name”.

Both he and Halas were at that meeting of team owners in 1933, when Marshall pitched the idea of banning black players. With the US in the depths of the Great Depression and millions of white people unemployed, he argued that paying black men to play football would be bad for business.

Pollard felt Halas held a personal grudge going back to when they were high school sports rivals in Chicago, and that he also played a prominent role in the ban being approved.

For decades the team owners claimed there was no unwritten agreement. The NFL has now acknowledged it did exist.

It didn’t end until the Los Angeles Rams signed Kenny Washington in 1946, and the NFL wasn’t fully reintegrated until 1962. Marshall’s Washington team was the last to sign a black player – after the government threatened to revoke the team’s lease on their publicly funded stadium if they did not.

Pollard became the second African-American in the College Hall of Fame in 1954. But when the Pro Football Hall of Fame opened in 1963, he was not among the charter class of 17 inductees. Five of the 11 men who had agreed to ban black players were, however.

At that time Pollard was 69 and the owner of several business ventures. After his playing career, he’d moved to New York with the Harlem Renaissance still in full swing and had become a talent agent, booking black entertainers for films and white nightclubs. He opened the Sun Tan Studios, where the likes of Duke Ellington and Nat King Cole rehearsed, and produced music videos called ‘soundies’.

He founded a newspaper, and set up an investment fund and a company trading coal. He later worked as a tax and public relations consultant.

“If anybody had the right to be angry about the way he was treated it was my grandfather, but he never showed it,” says Fritz III. “He always let his skills on the field, and his actions off it, define who he was. That’s something that was drummed into me.”

After Pollard, the second black starting quarterback was Marlin Briscoe in 1968. His case is typical of a process called ‘racial stacking’ which still influences the number of black head coaches we see today. There have been 24 in total, with three currently among the 32 teams, despite about 70% of NFL players being from ethnic minorities.

Briscoe passed for 14 touchdowns in 1968 – still a Denver Broncos record for a rookie. Yet the next summer Denver held quarterback meetings without him and he asked to be released. He never played quarterback again.

“African-Americans have historically been drummed out of the quarterback position and shifted into more ‘athletic’ positions like wide receiver, defensive back or running back,” says Professor N Jeremi Duru of American University in Washington DC, one of the leading experts in US sports law and discrimination.

“Offensive co-ordinators tend to come from quarterbacks, and head coaches from offensive co-ordinators, so the pipeline is thin for African-Americans because of discrimination against black players in so-called ‘thinking’ positions.”

When the Los Angeles Raiders hired Art Shell as head coach in 1989, he was asked in a live broadcast how it felt to be the NFL’s first black coach.

“But I’m not,” he said. “The first was Fritz Pollard.”

Fritz III recalls: “You could see all the reporters going ‘who’s Fritz Pollard?’ They had to cut to a commercial and then my phone just blew up with people saying ‘they’re talking about your grandfather’.”

Pollard had died just three years before, at the age of 92, but so many people were only hearing his name for the first time. It was time for his family to take up the story.

Pollard’s son Fritz Jr competed at the 1936 Olympics in Nazi Germany, winning a bronze medal in the 110m hurdles before serving in the US army in World War II. His grandson, Fritz III, became a three-sport All-American at college.

As Fritz Jr handed down his collection of memorabilia in the 1990s, Fritz III began contacting each member of the Hall of Fame’s 48-person selection committee, stating his grandfather’s case for inclusion. They’d then verify the information.

“They couldn’t find anything so I said ‘you’re looking in the wrong papers’,” says Fritz III. “After I told them about the historically black newspapers, a guy in Mississippi called back and said ‘did you know your grandfather averaged hundreds of yards a game?’ I said ‘yeah, I know, that’s what I’ve been telling you’.”

Fritz III’s daughter Meredith Kaye Russell, born in 1988, also joined the cause, helping with research and acting as her father’s secretary.

“It was a literal fight,” she says. “My dad was a single parent, and when he wasn’t working all the hours he did it was phone call after phone call, meeting after meeting, trying to get my great-grandfather’s name out there.”

What also helped build momentum was an advocacy group formed in 2003 that champions diversity and the hiring of NFL coaches, scouts and front-office staff from minority backgrounds. Fritz III gave his permission to name it the Fritz Pollard Alliance (FPA).

The FPA negotiated with the NFL to establish a rule requiring teams to interview at least one ethnic minority candidate for each head coach vacancy. It was named the Rooney Rule after Dan Rooney, former owner of the Pittsburgh Steelers, who at the time was chairman of the NFL’s diversity committee.

In 2020, there are three black coaches – the same as when the rule was instituted. For this reason the FPA has in recent years been vocal in flagging potential violations of the rule while seeking to enhance it. The rule now applies to general managers and co-ordinators too.

The FPA meets with the NFL formally twice a year to discuss proposals and collate a list of qualified minority candidates ready for interview.

“The league was challenged with a report showing that, essentially, African-Americans were the last hired and first fired,” says Duru, who worked with the FPA from its inception.

“Now it’s a healthy engagement, an exchange of ideas and not always agreement, but overall it’s a working relationship with open lines of communication.”

For Meredith, who teaches children aged three to eight, Pollard’s legacy has a power stretching beyond family and football.

“My students know I get so mad at them if they call themselves ‘stupid’. If they think they can’t do something or belittle themselves. I will not have that,” she says.

“This is a man who paved the way, who showed there is hope. Don’t let anyone tell you ‘no’. Keep working, keep going. It was really important to us as a family to get that known.

“Even if it helps just one person in the same situation as my great-grandfather, with the odds stacked against them, to persevere and make something of themselves, then it was worth it.”

[ad_2]

Source link