[ad_1]

Sitting on the hard shoulder on a searing hot day in California, Justin Williams was broken.

Through a wobbly heat haze along the Pacific Coast Highway, he watched as passing trucks and cars kicked up sheets of dust, forcing it down his throat. Resting on a pile of rubble next to his bike, he was barely able to raise a finger, let alone thumb a lift.

Williams’ bicycle was in perfect order. He hadn’t fallen off, but neither his brain nor body was working as it should. He’d ‘bonked’ – an endurance athlete’s term for when the body’s blood sugar is so low you can barely think straight, and your legs can no longer turn a pedal.

He was frustrated, helpless and confused.

Eventually a car pulled up, and the United States’ future national criterium racing champion was saved. By his aunt.

“For my first proper ride, my dad took me 70 miles,” Williams explains. “But the ride wasn’t the problem – he didn’t coach me through the eating and drinking.

“My dad was used to experiencing a lot of pain and suffering and he was adamant I needed to be serious about riding bikes. Bicycles are expensive. He told me: ‘This is not a game and if I’m going to invest in you, you need to be serious. This is real money.'”

Williams’ father Calman was one of Belize’s finest cyclists and a Pan-American Games competitor. His son would go on to become the USA’s first black national criterium and road racing champion.

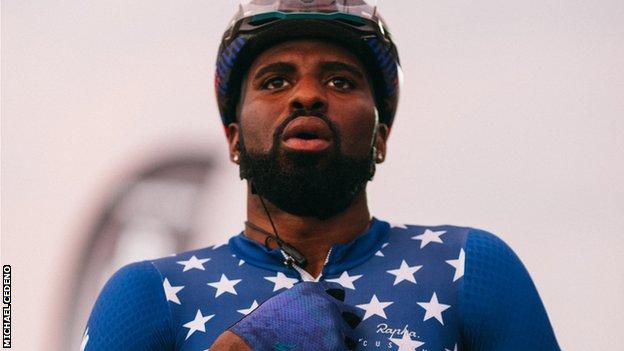

Justin Williams wears the stars and stripes with pride. But the journey that led him here is far from an American dream. Instead, his story is marked by years of disillusionment, poor pay and a lack of investment. He twice walked away from the sport before becoming champion. Now he’s part of a self-made team that is looking for another way, trying to make a difference from within.

Williams describes himself as a patriot. He has been vocal on social media following the death of George Floyd in May. He feels there’s an awful lot that needs to change.

In the USA. And in his own sport.

Growing up in south central Los Angeles, a budding cyclist needs to keep an eye out for pistols, not potholes. This is a town where people don’t take the bus, let alone ride a bike. It is where a long love affair with the car means 12-lane freeways are not likely to be given the temporary cycle lane treatment.

None of that held Williams back.

“The best thing about the black community is the sense of pride when something’s happening and that someone has a chance,” he says.

“People understand when somebody’s doing something beyond their circumstances. People recognise it’s something. I didn’t look like a typical guy riding bikes.”

Things got serious in 2007. At the age of 17, Williams turned professional, joining criterium team Rock Racing. For the next five years, he gave everything he had to the pro scene. It took him to the Trek-Livestrong development team, to bigger races across the USA, Europe and beyond, providing a young and severely underpaid Williams with a “culture shock”.

“It was too much of a dramatic shift,” he says. “So I came back home and went to college and got a job, which enabled me to realise I never wanted to work for anyone in my life!”

After taking some time off to find out “who he was”, Justin instead helped deliver his younger brother Cory into the sport, and into a team that recognised both brothers’ talent and potential.

Together, the pair began to make an impression on professional crit racing with a different team, Cylance.

“Cory had capabilities I didn’t have,” Justin says. “I wanted to show him he had support because I had been on my own. And that’s when our story really started to blossom.”

Criterium racing usually features a number of laps over a circuit in which rival teams try to break away and outfox their opponents until a furious final sprint. It attracts healthy crowds in towns and cities across the US.

The brothers went on to have one of their most successful years in 2016, winning some of the biggest races in the country. Cory won eight in a row, he and Justin working together, finishing each other’s moves.

“That bond you have with your brother – it’s hard to mimic two guys who have the same chemistry,” says Justin.

“But the next year, people had started saying the team was too much about us. God forbid that.”

Justin signed on for another year, on the understanding Cory would get a new deal too.

Cory’s contract offer never arrived.

“I begged for Justin to get on the team, and then I get fired,” says Cory, clearly still incredulous.

And this, for two African-American cyclists, is where the problem lies. A problem where black athletes are typecast along lines of racial prejudice, perhaps unconsciously. They face micro-aggressions that are no less painful despite the name.

Justin believes that athletes’ individualities are an afterthought in a structure “too European”. He feels riders are not afforded self-expression in protection of a team ethic that values conformity and compliance. He and Cory felt they didn’t belong.

“People in the sport don’t want to acknowledge the fact you have to work 10 times harder if you are black,” Justin says.

“There have been instances where Cory didn’t get the chances he deserved because they didn’t know him, and because he didn’t go around talking and smiling with them, they placed him as an angry person or a bad person and he missed opportunities based on that.

“I’m very outgoing, but that’s something that’s developed out of necessity. It runs deeper than me being an optimistic person. Being upbeat is part of my survival.

“Growing up in black America, if you aren’t inviting, people look at you in a certain way.”

Cory describes himself as “more introverted and shy” than his brother.

He adds: “People who know me know I’m a nice person and do a lot for people I know and love. If people want to think I’m some kind of way because we don’t know each other, they’re not worth trying to get to know.”

Disillusioned, Justin quit the sport for a second time. Cory continued with a different team on what was often an annual salary of $4,500 before winnings, which you share with a team of six. Not exactly living the dream.

Something had to change.

Alongside the stars and stripes on Justin’s jersey there is emblazoned a lion – a nod to his Rastafarian background. It represents the new direction he helped create himself.

In 2018, he got $18,000 from Specialized’s Rocket Espresso team. He used the money to fund himself around the European fixed gear racing circuit, functioning as an independent. After little more than a year, he was well into six figures in earnings as he made his own way through the sport, winning for himself.

“Fixed gear racing [where the bikes have only one gear and are harder to ride as a result] really embodies American culture,” Justin says. “I thought: ‘This is what cycling in America needs to be.’

“I was able to cultivate my own personal sponsorship, leading to me being in a better financial position. And I was having the most fun I’ve had by being on my own.”

Justin wanted others in his position to benefit – starting with Cory.

“I was having the best year ever showing up to cities like Milan, Barcelona and London, hanging out with friends, crashing on floors and actually enjoying the places I travelled to instead of just seeing an airport, a hotel, the race, back to the plane. I flipped it on its head,” Justin says.

“Cory was on an outdated structure on a pro team that doesn’t allow people to innovate. He got stuck and wasn’t allowed to go and make a name for himself. It didn’t make any sense.

“So I was like: ‘Let’s quit and race by ourselves.'”

L39ion of Los Angeles began in 2019. A team “dedicated to increasing diversity and encouraging inclusion”.

Justin says: “We let it be known from the gun that this is more than a cycling team.

“You hear growing up the ‘more than an athlete’ thing from LeBron James – that’s what I envisioned when I thought about making it as an athlete. About being in a position to make other people’s lives better and to influence someone’s life in a positive way.

“We started looking for people we believe in – and there’s a tonne of them. Alex Garcia, a kid I used to ride with, had to stop riding to help his mom. There’s nowhere to go to develop.

“It’s not all about winning – it’s a combination of everything that makes everything work: accessibility, results, social media, the way we position ourselves. That’s how the sport grows. You can see yourself in the sport if there is representation and it’ll make you wanna join.”

Legion raised $120,000 through crowd funding, although that doesn’t even cover all riders’ salaries for a year on minimum wages. Then there’s the cost of cars, flights, admin fees. Justin is filling the role of mechanic and manager himself to cut costs.

The team needs to be sustainable to be able to effect change. Justin and Corey feel they want to establish a sporting franchise that belongs to California, but they are also determined to expand across the country.

“For me, I want to build my own sport in America – thousands of fans screaming around a circuit in the middle of the city,” says Justin.

“Something needs to change. If we wait for other people to change, we’ll be waiting forever. I didn’t want to see my career go by in frustration and disappointment because I was too afraid to step outside of a box and do something different and new.”

This time they need more than a father figure, more than the support of a community – they need a whole sport to sit up and take notice.

“It’s all about creating superstars,” says Cory. “And cycling doesn’t have that. We want people to fall in love with a character. A superhero.”

[ad_2]

Source link