[ad_1]

People suffering from COVID-19 perform yoga inside a care centre at an indoor sports complex in New Delhi, India, July 21, 2020. Photo: Reuters/Adnan Abidi.

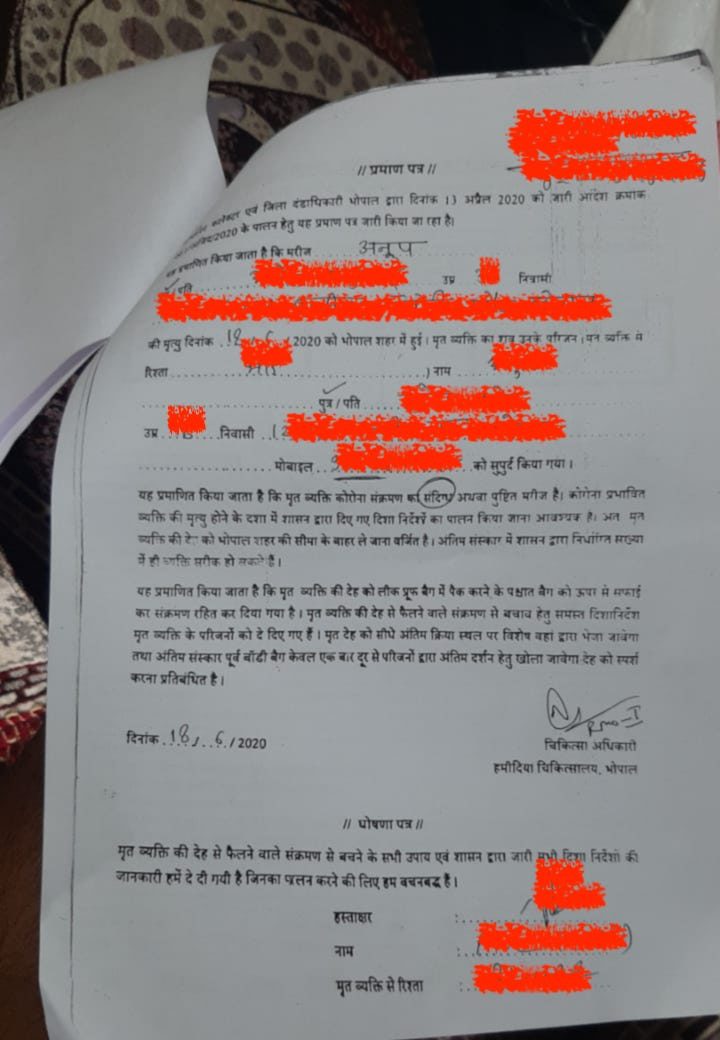

Bengaluru: Over a month-and-a-half after it happened, 36-year old Samar (name changed) still feels distraught about his brother Anup Majumdar’s death. Anup, two years older than Samar, was a computer operator at the Bhopal Municipal Corporation.

Both brothers were toddlers living a few kilometres away from Bhopal’s Union Carbide plant when in 1984 it leaked methyl isocyanate gas, killing thousands.

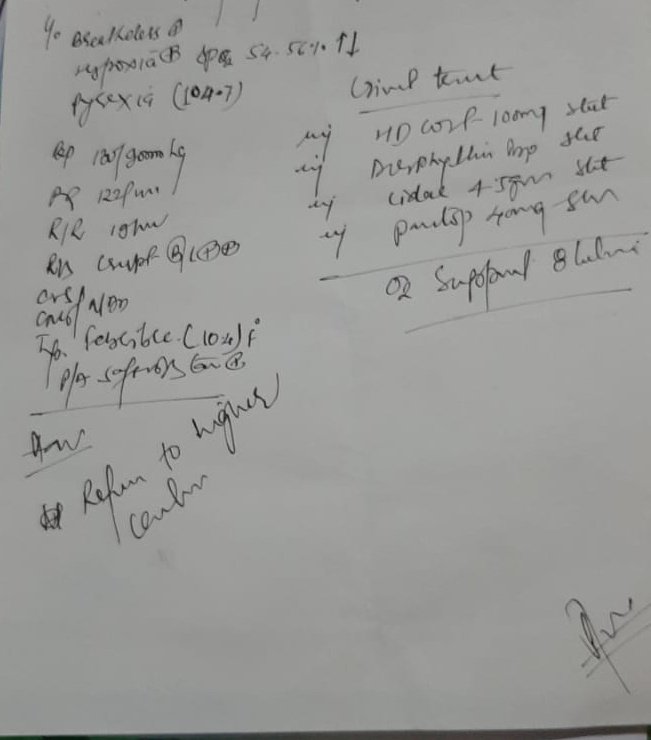

Sometime on June 17, 2020, when there were already quite a few COVID-19 cases in Bhopal, Anup began feeling breathless after two days of fever and cough. Worried that his elder brother may have COVID-19, Samar took him to cardiologist R.K. Dixit, whom the brothers had consulted before. Dixit told The Wire Science that the patient had several signs and symptoms of COVID-19.

Anup was subsequently admitted to the nearby New Star Hospital. An X-ray showed signs of pneumonia and his blood oxygen level was around 54% – both indications of COVID-19. After giving Anup oxygen, the doctors at New Star advised him to go to Hamidia Hospital in Bhopal, the designated government facility for COVID-19.

The brothers didn’t go to Hamidia for almost a day. Initially, Samar said, his brother was reluctant: “It is a government hospital with pathetic facilities. My brother used to hate it.” Instead, they visited two private hospitals but were either made to wait too long or were discouraged by the costs. Exhausted, they returned home that night. But when Anup began feeling breathless at around 3 am on June 18, Samar called an ambulance and took him to Hamidia.

§

By the time they reached the hospital, Anup was only able to walk up to a bed, before he died, even as Samar helped him lie down. A death summary from Hamidia Hospital says Anup was brought dead. The hospital collected a nasopharyngeal sample from Anup’s body to look for the novel coronavirus using a CBNAAT test. Like the RT-PCR, CBNAAT detects the virus by amplifying viral nucleic acids in a sample.

Meanwhile, the hospital told Samar that because Anup’s death was suspected to be due to COVID-19, the family couldn’t take his body home. Instead, the body would go directly to a crematorium, where the family could pay their last respects. So the family did that. The next day, several newspapers carried reports about Anup’s office being shut for disinfection.

This is why Samar was surprised a few days later when he learnt that his brother’s death was not counted by the city as a COVID-19 death. Rachna Dhingra, a social activist with the Bhopal Group for Information & Action, delivered the news. Dhingra had been checking daily death records maintained by Bhopal’s chief medical and health officer to see if deaths among gas-tragedy victims, whom she routinely works with, were being recorded. Anup’s death didn’t appear on this list for several days.

Samar, who still remembers the two traumatic days when he ferried his brother from hospital to hospital only to see him die, doesn’t understand any of this. The city administration didn’t allow the family to perform any last rites that involved touching the body, going by the protocol for suspected COVID-19 deaths.

Instead, the body was wrapped in plastic, and the family got to see Anup’s face for only a few minutes before cremation. Word also got around in the family’s neighbourhood that Anup died of COVID-19, so relatives and friends didn’t visit them for days.

Being rushed through the last rites was tough on the family. “Imagine what my mother went through, to lose her young son, and then be treated like this,” Samar said.

It was a triple blow: to lose a loved one, to pay a price for the death being linked to COVID-19 and then to be told the death wasn’t due to COVID-19.

Two categories of underreporting

Anup Majumdar’s death isn’t isolated. COVID-19 deaths are being underreported across India, an investigation by The Wire Science has found. Such non-reporting falls broadly into two categories.

In the first category, a city counts only those deaths of patients who tested positive for the virus – i.e. ‘confirmed COVID-19 deaths’ – in its official toll. When patients who have symptoms of COVID-19 but aren’t tested, test negative or have an inconclusive result die, their deaths aren’t included.

While epidemiologists refer to such deaths variously as ‘suspected COVID-19 deaths’, ‘probable COVID-19 deaths’ and ‘clinically diagnosed COVID-19 deaths’ – based on several criteria – this article will use the blanket term ‘suspected deaths’ for all of them.

Anup’s death was a suspected death. Hamidia Hospital’s CBNAAT test came back negative, Simmi Dube, an internal medicine specialist at the hospital and a member of the hospital’s death-audit committee, which reviewed Anup’s records, said. As a result, doctors couldn’t be sure if Anup had died due to COVID-19 or of some other cause, like bacterial pneumonia or influenza, which cause similar symptoms, Dube added.

However, a negative result doesn’t mean a doctor has no idea of the cause of death at all. Dube’s committee had access to doctors’ notes written and the X-ray scan from New Star Hospital, which Anup’s brother Samar had submitted.

The Wire Science consulted three doctors: virologist T. Jacob John; pulmonologist Parvaiz Koul from Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar; and radiologist Vijay Sadasivam from S.K.S. Hospital, Salem, for their opinions. Both John and Koul agreed that the patient’s recorded symptoms and the X-ray pointed to suspected COVID-19. “A young person with symptoms and hypoxia and the radiography suggestive of bilateral pneumonia strongly suggests COVID-19,” Koul said. Sadasivam also said the X-ray was consistent with COVID-19.

Despite there being other ways to diagnose COVID-19 patients, most Indian states are not reporting suspected deaths. The Wire Science spoke to municipal officials, health-department officials and officials from the Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme in seven states and union territories: Maharashtra, Gujarat, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Puducherry, all of whom said they weren’t including suspected deaths in their published COVID-19 death tolls.

And this isn’t the only kind of underreporting there is. Some Indian cities and states are going a step ahead and not reporting all confirmed deaths either. These include Gujarat’s Vadodara and Surat, and all of Telangana. Together, both kinds of underreporting risk giving a false picture of COVID-19’s real impact in India.

The first category – suspected deaths

Suspected deaths make up a major blindspot for India because all nucleic acid tests used to confirm COVID-19, like CBNAAT and RT-PCR, sometimes return false negatives. So even a patient who is infected with the virus can test negative. More than 30% of RT-PCR results can be falsely negative depending on when the patient’s sample was collected.

Another issue with not reporting suspected deaths is that several states still conduct too few RT-PCR tests, ergo many infections may never be confirmed. When some of these people die, not counting them among COVID-19’s victims can deflate the disease’s death toll.

For these reasons, a clinical diagnosis, which a doctor makes based on a person’s symptoms, along with other signs, like a telltale haze on X-rays or CT scans and low blood-oxygen levels, is a more dependable way to identify COVID-19 patients, John said.

“For all diseases, clinical diagnosis is fundamental, more so in an epidemic. Lab testing is additional evidence.” According to him, “Between clinical criteria and a lab test, the former is more reliable, unless both tally.”

Given these facts, several countries have recognised that counting suspected deaths is crucial to getting a true picture of COVID-19’s impact. In April, for example, the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention asked American states to start reporting “probable deaths” apart from confirmed deaths as well. Probable deaths are deaths among patients with COVID-19 symptoms, who have lived in or travelled to an area with community transmission, and who don’t have positive results from nucleic-acid tests.

As on August 2, 24 out of 60 US jurisdictions were publishing the count of probable deaths separately, and such deaths constituted 6% of the 152,870 deaths reported in the US until then.

In India, however, it isn’t clear if suspected deaths are being captured anywhere at all. Himanshu Chauhan, joint director of the National Centre for Disease Control, Delhi, told The Wire Science that all states were only submitting confirmed death data to the Union health ministry. This means that India’s official death toll – 37,364 at the time of writing – only includes confirmed deaths.

The many suspected deaths of Bhopal

So how many suspected deaths could be missing in India? One clue to the answer lies in the large mismatches between the numbers of bodies cremated or buried according to COVID-19 protocols and the official tallies published by cities.

In March 2020, the health ministry published guidelines on how to handle the bodies of patients who have died due to COVID-19 to minimise the virus’s spread. Crematoria and burial grounds thus had to take extra precautions with each body – and ended up maintaining a count of them. Subsequently, observers have been able to identify differences in the numbers of COVID-19 suspected deaths and reported deaths in many cities.

On June 27, journalist Kashif Kakvi reported for NewsClick that three of Bhopal’s crematoria and one graveyard had handled 180 bodies with COVID-19 until June 24. However, the city had only reported 91 deaths until then. K.V.S. Chaudhary, the commissioner of Bhopal Municipal Corporation, told The Wire Science that the excess deaths belonged to the “suspected” category. At the time of writing, these excess deaths hadn’t been reconciled with the city’s official toll.

Meanwhile, Bhopal’s Rachna Dhingra has been trying to identify several patients that died but remained uncounted at the city’s Chirayu Hospital and the Bhopal Memorial Hospital and Research Centre. In the last few months, she scoured through the official list of deaths maintained by the chief medical and health officer (CMHO) and compared it with COVID-19 deaths among survivors from the 1984 tragedy, and their children.

The Wire Science spoke to the relatives and doctors of four such patients Dhingra discovered. Their stories are reproduced at the end of this article, in a section entitled ‘Who Are Bhopal’s Uncounted?’, and separately here. They indicate just how doctors strongly suspected COVID-19 in some of the cases – but didn’t record it only because state reporting systems had no provisions to do so.

The second category – confirmed deaths

While not reporting suspected deaths seems to be the norm in all states, it’s not the only kind of undercounting happening in India. Some states are also not counting many confirmed deaths. Instead, they have been attributing a fraction of such confirmed deaths to comorbidities – pre-existing conditions the patient may have had, like diabetes, cancer or AIDS, that worsen the effects of COVID-19. These so-called “deaths due to comorbidities” are then excluded from these states’ death tolls.

To understand why ascribing a confirmed COVID-19 death to comorbidities is a problem, we need to understand how doctors record the causes of deaths.

Typically, for a certain fraction of deaths, doctors issue a medical certificate of cause of death (MCCD). This document lists the chain of events, culminating with mortality. A doctor writes the immediate cause of death as the first step in this chain. For COVID-19 patients, this is often acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), the condition that manifests as breathlessness. Next, the doctor mentions the antecedent cause of death – the condition that led to the immediate cause of death. For a COVID-19 patient, this could be pneumonia, an inflammation of the lungs’ air sacs, which in turn leads to ARDS.

The doctor finally enters the underlying cause of death below the first antecedent cause on the MCCD. This is the disease that caused both the immediate and antecedent conditions. For patients who died of COVID-19, the doctor would write ‘COVID-19’ here. But the MCCD doesn’t end here. It also has a section called “other significant conditions contributing to the death but not related to the disease”. Here, the doctor includes the comorbidities, like diabetes, coronary artery disease, hypertension, tuberculosis or AIDS, that may have worsened the disease.

While the sequence recorded in an MCCD depends on the doctor’s judgement, mistakes are not uncommon. The Indian Council for Medical Research’s (ICMR’s) guidelines for COVID-19 death certification warn against one such mistake. They recommend doctors not enter comorbidities as the underlying cause of death in people who died with a COVID-19 infection. The reason is that deaths due to complications from comorbidities in someone infected with COVID-19 are typically uncommon at the height of a pandemic.

While there could be deaths where confirmed COVID-19 patients don’t die of pneumonia – succumbing instead to a complication of a comorbidity – these cases are rare, several experts told The Wire Science. One example would be an asymptomatic COVID-19 carrier with chronic diabetes dying from ketoacidosis – a diabetic complication that causes acids to build up in the blood.

“But most deaths among people with diabetes wouldn’t have happened if they hadn’t been infected by the virus,” T. Sundarraman, a health systems researcher in Puducherry, said.

There is evidence that at least two cities in Gujarat, Vadodara and Surat, and all districts of Telangana are flouting the ICMR guidelines. All of them are naming comorbidities as the underlying cause in a large number of confirmed deaths, and aren’t counting such deaths in their official tallies.

For example, Devesh Patel, a medical officer of health at the Vadodara Municipal Corporation, previously told the British Medical Journal that the city’s death audit committees were attributing 75-80% of deaths to comorbidities. When asked how deaths due to comorbidities were identified, he said it depended on how long the patient had suffered the comorbidity.

“If a person has diabetes for not very long, the likelihood of him or her developing a crisis due to diabetes, like ketoacidosis, is less likely,” Patel told The Wire Science. “If the same person had diabetes for 25-30 years, and it could have led to a crisis like ketoacidosis, then they won’t be classified as COVID-19.”

This misclassification is reflected in Vadodara’s unusually low death toll: even though the number of cases has grown 329% in the last two months to 4,945 today, the number of deaths has grown only by 49%, from 63 to 94, in the same time.

Indeed, Vadodara is an obvious example of undercounting, several experts told The Wire Science. “This cannot happen. For a new epidemic like COVID-19, it is unlikely that we can have something else as the cause of death in 75% of COVID-19 positive cases,” Hemant D. Shewade, senior fellow of operational research at The Union, Bengaluru, said. He argued that in the early stages of a new pandemic, most people have no immunity, which means the virus itself will be the underlying cause that makes vulnerable people die. So for 75% of people to be infected with COVID-19 and then to die from something else, he said, was inexplicable.

Surat has been undertaking a similarly questionable death classification exercise. Surat Municipal Corporation’s medical officer of health P.H. Umrigar also confirmed the city wasn’t including deaths due to comorbidities in its toll. And when asked how the city was identifying such deaths, he offered several examples.

“In those who have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma or are chain-smokers, lungs are already compromised, and COVID-19 may be superimposed on the underlying illness,” Umrigar told The Wire Science. “Such a person may be COVID-19 positive, but the primary cause may be something else, like asthma or COPD. Also, when patients who are immunocompromised with diseases like HIV or tuberculosis die, COVID-19 is not the cause of death.”

Umrigar said he wasn’t sure how many deaths fell into this category in Surat, but said it could be around 20-30% of all confirmed deaths.

In similar vein, Telangana’s health minister Eatala Rajender said on May 16 that the state wouldn’t include deaths due to comorbidities in its COVID-19 toll – in keeping with ICMR guidelines for death certification. But Rajender’s interpretation is the opposite of what ICMR has said: that comorbidities should not be considered to be causes of death.

As a result, the state’s reported death toll on July 31 – 519 – may be the result of a massive undercount. The day’s media bulletin said 53.8% of deaths in the state were due to comorbidities, which means the state may actually have confirmed 963 deaths by then.

The causes of death

Identifying the underlying cause of death is rarely straightforward.

But several experts argue that it’d be prudent to attribute most confirmed deaths in the current pandemic to COVID-19 – despite the fact that there will be clear-cut exceptions, when a person confirmed to have COVID-19 dies of something else. For example, if an asymptomatic carrier is hit by a truck, the underlying cause of death would be a motor vehicle accident.

There are also borderline cases. For instance, if an asymptomatic carrier suffers a heart attack – the common term for a myocardial infarction – due to preexisting coronary artery disease, a doctor could argue that the underlying cause of death was a complication of the comorbidity, viz. coronary artery disease. Given that the person never developed pneumonia or other respiratory symptoms, by dint of being asymptomatic, the doctor’s argument may be justified.

However, as researchers uncover new information about how exactly COVID-19 kills, the underlying cause of death in many cases where the patient has few respiratory symptoms is also swinging in favour of COVID-19. Scientists now know that one way COVID-19 manifests is as a pulmonary embolism – a blood clot in an artery in the lung. This can trigger a heart attack even in an asymptomatic COVID-19 carrier or a patient with mild respiratory symptoms.

If such a heart attack kills the person, it would be hard to pinpoint the cause, Swapnil Hiremath, a nephrologist at the Ottawa Hospital in Canada, said. “Was it because of a myocardial infarction from another cause – that is, underlying coronary artery disease? Was it because of COVID and a massive pulmonary embolism?” he said. Without an autopsy, it’s difficult to know for sure, but according to him, COVID-19 could easily be the trigger.

Hiremath has been looking into COVID-19’s impact on the kidneys, and said that in exceptional cases, COVID-19 can injure a patient’s kidneys without triggering any respiratory symptoms. A team of researchers at New York’s Mt Sinai Hospital have documented how patients confirmed to have COVID-19 with no symptoms can suffer strokes.

Given the different organs COVID-19 can target, attributing most confirmed deaths to COVID-19 is the most pragmatic way to avoid missing pandemic deaths, even if it is not 100% accurate, several researchers told The Wire Science. Because undercounting is a real worry in a pandemic, “it’s important not to miss any deaths, even if it means erring on the side of over-attribution of COVID-19 as a cause of death,” Prabhat Jha, an epidemiologist at the University of Toronto, said.

This practice may inflate deaths a little, but not much, according to many experts. Sundarraman argued this point with the example of a person with COVID-19 dying of a heart attack. While the death could either be due to COVID-19 or due to coronary artery disease, the chances that a person died of the latter during the short period that she was infected with the virus would be tiny, he said.

He also calculated that with only over 570,000 active cases in the country today, roughly four of every 10,000 Indians would test positive for the virus. And these four people would test positive with an RT-PCR test only in a 7-10-day window. So for a heart-attack death to be erroneously attributed to COVID-19, a COVID-19 carrier would have had to suffer the attack due to an unrelated reason in those 7-10 days. “To say there will be many such overlaps doesn’t make any sense,” Sundarraman said.

The quest to capture missing deaths

India’s current reporting system allows many deaths to go missing – but there could be alternative methods to track them down. One is the countrywide MCCD scheme, under which over 57,000 large medical colleges and hospitals fill MCCDs for each death in their premises and submit it to the respective state death registrar.

If these institutions followed ICMR guidelines to certify COVID-19 deaths, they would record suspected COVID-19 deaths as well. And even in states that mistakenly list comorbidities as the underlying causes of death, doctors will likely enter COVID-19 under the “other significant conditions” section, allowing experts to reanalyse the causes later. Shewade said that in cities like Vadodara, where there are doubts about the misclassification of deaths, an independent medical examiner could review the causes of death at a later date, provided all deaths have been medically certified.

There is an issue, however: the MCCD scheme covers only a fraction of deaths in India. According to the 2018 Report on Medical Certification of Cause of Death – the latest thus far – only 21.1% of all registered deaths were medically certified in the county that year, and most certificates originated in urban hospitals. So as the virus spreads into rural India, there is no way to capture suspected deaths there, said Jha. This is a problem because relying on urban cause-of-death data will underestimate the epidemic, as well as miss deaths occurring at home, which often go medically uncertified.

To bridge this gap, Jha has previously called for large verbal autopsy surveys in India, in which non-medical workers visit homes and collect information from families on recent deaths in a simple format. This information is later assessed by medical professionals to assign an underlying cause of death. But India hasn’t initiated any such survey thus far for COVID-19.

Another solution is for the Centre to request states to report suspected COVID-19 deaths, alongside confirmed deaths, Sundarraman said. At present, only MCCDs contain the option of suspected deaths. But he said there ought to be a way for doctors to report such deaths even when they don’t write MCCDs.

Back in Bhopal, Anup Majumdar’s brother Samar is weighed down by other considerations. Both brothers were employed as contract workers, and were the only earning members in a family of five. Now, his brother is no more, and even as Samar grieves his loss, he is worried for his family’s financial security. At the time of writing, his mother, who suffers from diabetes and hypertension, had also tested positive for COVID-19, and Samar was scrambling to find a hospital to get her admitted. Just the fact that his brother’s death was never counted as a COVID-19 death is not the biggest of his worries – it’s simply one of many.

But he wonders if the Madhya Pradesh government will know how badly the pandemic has hurt families like his if it doesn’t know what the true burden of the disease is.

“They must count the deaths. Otherwise, they can keep claiming that the outbreak wasn’t really that bad,” he said.

Note: A July 17 article by Priyanka Pulla in the British Medical Journal referred to the late Anup Majumdar by the pseudonym Suresh. Anup’s family has since agreed to use his real name. But in keeping with the family’s wishes, this article refers to Anup’s brother by a pseudonym.

Priyanka Pulla is a science writer.

The reporting for this story was funded by a public health journalism grant to Priyanka Pulla from The Thakur Family Foundation.

Editor’s note: Except Mohammed Naseem, the names of the other three patients described below have been changed to protect their identities.

I

Manish, 27, was admitted to the People’s Hospital in Bhopal on July 7, when he suffered a ruptured liver abscess. After doctors operated on him, he developed respiratory symptoms indicative of COVID-19. Manish’s family then moved him to Chirayu Hospital, a designated COVID-19 hospital in the city.

Here, Ajay Goenka, the hospital’s director, ordered a CT scan that showed Manish had fluid in both lungs, a sign of possible COVID-19. As his condition worsened, Goenka said, the doctors inserted a tube through his windpipe to help him breathe and a nasogastric tube for him to receive food and medicine. However, these devices made it harder for health workers to collect a proper swab from the patient’s nasopharynx for an RT-PCR test.

Manish eventually died a week later, on July 14. “We definitely thought he had COVID-19 because there was indirect evidence from the CT-scan,” Goenka said. “But in India, we are not declaring any deaths as confirmed COVID-19, until they are proven by RT-PCR.” Thus, the death wasn’t reported as a COVID-19 death.

II

The second patient, 45-year-old Mohammed Naseem, was admitted to Bhopal’s Apex Hospital in July for gastric complaints, including vomiting. He had been diabetic for many years until then. His brother, Mohammed Nafees, said Naseem suffered a heart attack at the hospital. For reasons that aren’t clear, the doctors suspected he had COVID-19. Nafees said the hospital didn’t give his family any documents.

Eventually, the family shifted Naseem to Chirayu. Here, Nafees said, doctors told him that a CT scan showed signs of COVID-19 in Naseem’s lungs – but on the other hand the RT-PCR test had come back negative.

Naseem died on July 21. The hospital labelled the death a suspected COVID-19 death, and the body was buried accordingly. The Wire Science reached out to Chirayu’s director Ajay Goenka to discuss more details of the case but received no response.

III

Salim, 43, was admitted to Bhopal Memorial Hospital & Research Centre, which is dedicated to victims of the 1984 tragedy, on July 23. At the time he had typical COVID-19 symptoms, including breathlessness and low blood oxygen, and a CT showed pneumonia in both lungs, Mukesh Jatav, a doctor in the hospital’s pulmonary medicine department, told The Wire Science.

Salim passed away within hours of being admitted. Jatav said the hospital was collecting a swab from Salim for an RT-PCR test at the time of his death. Since no result was immediately available, Jatav entered “?? COVID-19” as the underlying cause of death on the medical certificate of cause of death, a document that describes the chain of events leading up to death. Jatav said he meant for the question marks to mean that the death was due to suspected COVID-19.

The RT-PCR later came back negative – so Salim’s death wasn’t reported as a confirmed death to the city. Jatav admitted that a negative result could mean the patient really had COVID-19 and that testing a second sample could improve the rate of detection. “But usually, there is no time to take a second sample from a patient. And there is no rule for saving a sample to test later,” he said.

IV

Bashir, 55, was admitted to Bhopal Memorial Hospital & Research Centre with complaints of fever and breathlessness. He also suffered from diabetes and hypertension. When he died on July 19, his name didn’t enter the list of COVID-19 deaths maintained by the city until eight days later.

Lalit Kumar, a doctor at the pulmonary medicine department at Bhopal Memorial, told The Wire Science that when Bashir died, his swab sample had been sent for an RT-PCR test, but the result wasn’t yet available. However, soon after, it came back positive, and the hospital informed the CMHO’s office.

Given these details, it remains unclear why the list of fatalities at the CMHO’s office wasn’t updated even eight days later, although the hospital claims it communicated the positive results to the CMHO’s office online almost immediately.

This suggests that the Bhopal city administration may not be updating death numbers even in confirmed cases, if the RT-PCR results arrive with a delay after the death. Prabhakar Tiwari, the CMHO, didn’t respond to questions from The Wire Science on the matter.

[ad_2]

Source link