[ad_1]

Image copyright

Image copyright

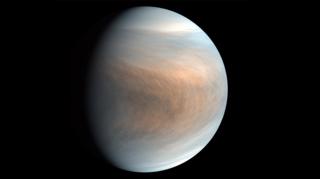

JAXA/ISAS/Akatsuki Project Team

Planet Venus: The phosphine is detected at mid-latitudes

It’s an extraordinary possibility – the idea that living organisms are floating in the clouds of Planet Venus.

But this is what astronomers are now considering after detecting a gas in the atmosphere they can’t explain.

That gas is phosphine – a molecule made up of one phosphorus atom and three hydrogen atoms.

On Earth, phosphine is associated with life, with microbes living in the guts of animals like penguins, or in oxygen-poor environments such as swamps.

For sure, you can make it industrially, but there are no factories on Venus; and there are certainly no penguins.

So why is this gas there, 50km up from the planet’s surface? Prof Jane Greaves, from Cardiff University, UK and colleagues are asking just this question.

They’ve published a paper in the journal Nature Astronomy detailing their observations of phosphine at Venus, as well as the investigations they’ve made to try to show this molecule could have a natural, non-biological origin.

But for the moment, they’re stumped – as they tell the BBC’s Sky At Night programme, which has talked at length to the team. You can see the show on BBC Four tonight (Monday) at 22:30 BST.

Given everything we know about Venus and the conditions that exist there, no-one has yet been able to describe an abiotic pathway to phosphine, not in the quantities that have been detected. This means a life source deserves consideration.

“Through my whole career I have been interested in the search for life elsewhere in the Universe, so I’m just blown away that this is even possible,” Prof Greaves said. “But, yes, we are genuinely encouraging other people to tell us what we might have missed. Our paper and data are open access; this is how science works.”

Media playback is unsupported on your device

What exactly has the team detected?

Prof Greaves’ team first identified phosphine at Venus using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii, and then confirmed its presence using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile.

Phosphine has a distinctive “absorption line” that these radio telescopes discern at a wavelength of about 1mm. The gas is observed at mid-latitudes on the planet at roughly 50-60km in altitude. The concentration is small – making up only 10-20 parts in every billion atmospheric molecules – but in this context, that’s a lot.

Image copyright

ESO/M.Kornmesser/L.Calcada/Nasa

The phosphine molecule is made up of one phosphorus atom and three hydrogen atoms

Why is this so interesting?

Venus is not at the top of the list when thinking of life elsewhere in our Solar System. Compared to Earth, it’s a hellhole. With 96% of the atmosphere made up of carbon dioxide, it has experienced a runaway greenhouse effect. Surface temperatures are like those in a pizza oven – over 400 degrees.

Space probes that have landed on the planet have survived just minutes before breaking down. And yet, go 50km up and it’s actually “shirtsleeves conditions”. So, if there really is life on Venus, this is exactly where we might expect to find it.

Image copyright

DETLEV VAN RAVENSWAAY/SPL

Artwork: Venus is envisioned as a hellish world, an unlikely candidate to host life

Why should we be sceptical?

The clouds. They’re thick and they’re mainly composed (75-95%) of sulphuric acid, which is catastrophic for the cellular structures that make up living organisms on Earth.

Dr William Bains, who’s affiliated to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the US, is a biochemist on the team. He’s studied various combinations of different compounds expected to be on Venus; he’s examined whether volcanoes, lightning and even meteorites could play a role in making PH3 – and all of the chemical reactions he’s investigated, he says, are 10,000 times too weak to produce the amount of phosphine that’s been observed.

To survive the sulphuric acid, Dr Bains believes, airborne Venusian microbes would either have to use some unknown, radically different biochemistry, or evolve a kind of armour.

“In principle, a more water-loving life could hide itself away inside a protective shell of some sorts inside the sulphuric acid droplets,” he told Sky At Night. “We’re talking bacteria surrounding themselves by something tougher than Teflon and completely sealing themselves in. But then how do they eat? How do they exchange gases? It’s a real paradox.”

The Soviet probes that landed survived just long enough to radio back a handful of pictures

What’s been the reaction?

Cautious and intrigued. The team emphatically is not claiming to have found life on Venus, only that the idea needs to be further explored as scientists also hunt down any overlooked geological or abiotic chemical pathways to phosphine.

Oxford University’s Dr Colin Wilson worked on the European Space Agency’s Venus Express probe (2006-2014), and is a leading figure in the development of a new mission concept called EnVision. He said Prof Greaves’ observations would spur a new wave of research at the planet.

“It’s really exciting and will lead to new discoveries – even if the original phosphine detection were to turn out to be a spectroscopic misinterpretation, which I don’t think it will. I think that life in Venus’ clouds today is so unlikely that we’ll find other chemical pathways of creating phosphine in the atmosphere – but we’ll discover lots of interesting things about Venus in this search,” he told BBC News.

Dr Lewis Dartnell from the University of Westminster is similarly cautious. He’s an astrobiologist – someone who studies the possibilities of life beyond Earth. He thinks Mars or the moons of Jupiter and Saturn are a better bet to find life.

“If life can survive in the upper cloud-decks of Venus – that’s very illuminating, because it means maybe life is very common in our galaxy as a whole. Maybe life doesn’t need very Earth-like planets and could survive on other, hellishly-hot, Venus-like planets across the Milky Way.”

Image copyright

ESO

The phosphine signal was confirmed by the ALMA telescope facility in Chile

How can the question be resolved?

By sending a probe to investigate specifically the atmosphere of Venus.

The US space agency (Nasa) asked scientists recently to sketch the design for a potential flagship mission in the 2030s. Flagships are the most capable – and most expensive – ventures undertaken by Nasa. This particular concept proposed an aerobot, or instrumented balloon, to travel through the clouds of Venus.

“The Russians did this with their Vega balloon (in 1985),” said team-member Prof Sara Seager from MIT. “It was coated with Teflon to protect it from sulphuric acid and floated around for a couple of days, making measurements.

“We could definitely go make some in-situ measurements. We could concentrate the droplets and measure their properties. We could even bring a microscope along and try to look for life itself.”

Image copyright

NASA-JPL/Caltech

Artwork: One of the best ways to resolve the uncertainty would be with instrumented balloons

The Sky At Night special on this story can be seen at 22:30 on BBC Four, and afterwards on the BBC iPlayer.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos

[ad_2]

Source link