[ad_1]

On Jan. 15, Karl-Anthony Towns tested positive for COVID-19. Just nine months after the 25-year-old watched his mother, Jacqueline Towns, die of the same disease that also killed his uncle and five other members of his family, this was a nightmare scenario.

Towns received treatment at an area hospital, then quarantined at home for the next few weeks, isolated from friends and family. Basketball had been the closest thing in his life to an outlet. Now, by himself, he had no choice but to confront the pain that followed his mother’s sudden death.

“I’ve had a lot of situations this year where things were just too much for me,” Towns says. “I just remember [quarantining] in the house, and it was more than just COVID for me. I felt like I was going through a holistic journey.”

On Feb. 1, Towns was cleared to join the team on a road trip that began in Cleveland. He had worked his way back after losing 50 pounds while recovering from COVID-19. “I was as big as D’Angelo [Russell],” he jokes. “I was as big as our guards. You think I’m gonna play center?”

A high-calorie diet eventually solved his weight problem. But that night inside Quicken Loans Arena, in the same building with so many people for the first time since he was able to leave his house, anxiety enveloped Towns on the bench. When the first quarter ended he texted his agent: “I can’t be out here anymore. I can’t do this.” He rushed back to the locker room, where Minnesota’s head equipment manager Peter Warden asked if everything was O.K.

Towns was having symptoms of a panic attack. He was sweating and his chest was tight. He contemplated leaving the arena and traveling back to the hotel or even flying himself to Minnesota, but stayed in the back until the game ended. It was the first time Towns had ever felt that way around a basketball court. “It was too much for me,” he says. “My skin was itching.”

Nine days later, Towns finally put his jersey back on for a home game against the Clippers. But to this day he can’t describe exactly how his emotions allowed him to return to the floor.

Thousands have endured the death of someone they love during a pandemic that’s still devastating families all over the world, but Towns had to grieve in public. An intimate agony turned communal, be it during his postgame video scrums with the media, games before and after Easter Sunday around the one-year anniversary of his mother’s death or on Mother’s Day on the road in Orlando. All the while, Towns tried expressing himself as honestly as he could, but his words barely scratched the surface of what roiled inside.

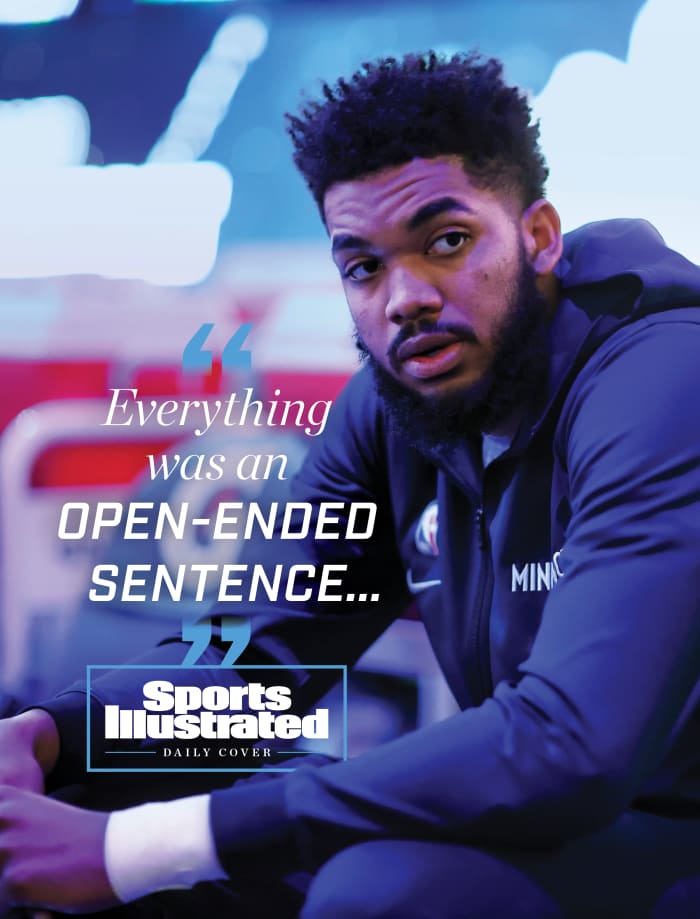

“I felt like everything was an open-ended sentence, you know? There was no closure. There was no period at the end,” he says. “I just kept running on and running on and running on, but I never really got to where I needed to go to end a conversation.”

There were days when being around teammates carried him. Basketball felt like it could provide a blip of relief. There were others when he thought about stepping away and giving himself space to mourn. “[My mother] made basketball fun for me my whole entire life,” Towns says. “She made it where I wanted to even do this. So for me, I was like, [There’s] too much on my mind. I’m not, I can’t, nah, I can’t.”

His father, Karl Towns Sr., told him to take his time and prioritize his own mental health, while laying out what an indefinite leave of absence would mean for his son. KAT decided to keep playing, but made it clear financial ramifications weren’t a concern.

“That money s— don’t mean s— to me,” he says. “Time is the real thing we losing every day. I just really didn’t think I could play the game of basketball the way I want to represent myself in the NBA. I didn’t want to represent myself in a bad way. There’d be a lot of times we’d play a game. Game’s over. And I’m not even in there. I’m doing my own thing. I’m in the bathroom looking at myself, wondering if this is the man that I really think I am. I had 40. I’m still not happy with the man I see in the mirror. I’m still dealing with a lot of s—.”

Throughout last season, Towns couldn’t find the words to express how he was really feeling.

David Sherman/NBAE/Getty Images

Towns, who has remained largely silent on the subject until now, says that during the season there was no opportunity to process his own heartache. So much energy was spent worrying about others, and he didn’t want to let anybody down. Not the fans who were trickling into the Target Center. Not the teammates who supported him as best they could. Not his new coach, Chris Finch, who texted Towns at 2 a.m. on Feb. 22 to introduce himself.

But the desire to put everybody else’s feelings before his own split him in half. He still gets emotional describing the weight placed on his shoulders last year, ultimately admitting: “I never got a chance to really sit down and say, ‘Hey Karl, what do you need?’ ”

Before home games last season, Towns would walk into Finch’s office with a latte in his hand, sit down and chat. Most conversations covered their shared Philadelphia Eagles obsession or baseball, specifically the American League East standings. “We’d just talk about these little commonalities that we’ve had that give us a chance to shoot the s—, so to speak,” Finch says.

In getting to know each other, Towns and Finch would also discuss different ways they could take advantage of his singular skill-set, be it specific plays Tom Thibodeau used to call when he was Minnesota’s coach or broader opportunities to run the offense through him. Finch recalls Towns specifically highlighting one play from his rookie season during a victory over the 73-win Warriors where he glued himself to Steph Curry. Says Finch, “He’s like, ‘I can guard this guy! I can guard that guy!’ ” Finch later looked up Towns’s numbers switching screens and was impressed. “There’s not anything on the floor he doesn’t think he can do, which is what you want from your best player.”

But since Towns was voted as the No. 1 player NBA general managers would most want to build a team around before the 2016–17 and ’17–18 seasons (directly ahead of Kevin Durant and Giannis Antetokounmpo, respectively) his career has lost some propulsiveness. Towns hasn’t won a playoff series during his six NBA seasons. His first and only postseason appearance came three years ago, on the back of a combustible partnership with Jimmy Butler and Thibodeau, which eventually led to the hiring of Gersson Rosas as Minnesota’s president of basketball operations right before a pair of pandemic-shortened seasons.

“I expected to be in a much different situation,” Towns says. “After my third year, with us making it to the playoffs—having that experience, knowing what it takes, knowing what to listen to, knowing who not to listen to, what not to listen to, I had a good grasp on what the young guys needed to hear—I was hoping we would take that playoff run and build a culture around it. But things have changed a lot in Minnesota. Every year. So it’s hard. It’s been hard to build a culture with young guys and everything, when everything’s not static.”

(Not even three weeks after Towns said this, Rosas was abruptly terminated after it was reported he had an extramarital affair with a coworker. Rosas was replaced by Timberwolves executive vice president of basketball operations Sachin Gupta.)

As best he could, through sadness and physical injuries, Towns tried turning things around last season; even in a losing environment there were clear traces of the revolutionary big man who helped change the league when he entered it, particularly in minutes alongside Russell and rookie Anthony Edwards.

Towns brought the ball up and kick-started sets like a point guard. He came off screens. He posted up. He popped for threes. He initiated dribble handoffs from the elbow and was the pick-and-roll ballhandler. “When you have skilled bigs you can kind of flip the court on people,” Finch says. “We want him to have as many early touches in the offense as possible, not just to feed himself, but his passing skills are elite. I was fortunate enough to work with [Nikola] Jokić. Their skill sets are so, so, so similar.”

It’s easy to take Towns’s remarkable repertoire for granted, watching a center mow down opponents with the instincts and fluidity of a guard. He thinks some have: “Don’t get it twisted. [Jokić] is definitely amazing when it comes to passing, and his teammates know where he’s at. The system they have, it’s almost perfectly tailored for him. And obviously it has to be if you’re gonna win MVP. But I’ve been doing that my whole career.”

There might not be 10 players alive who can single-handedly mangle a defensive scheme in all the ways he does, some of which have yet to be explored. “There’s a lot of things I work on in the offseason every year that we never utilize, and one day we’re going to utilize it and you’re gonna say, ‘Damn, he could do that?’ And I’m gonna be like, ‘F— yeah, I could do that! I’ve been doing this s—!’ ” Towns says, laughing. “There’s a lot of my game out here I feel I haven’t shown. . . . And if I get a chance, s— is gonna get real spooky and scary for people.”

Towns is one of 17 players in NBA history—the only active player—to record at least 9,000 points, 4,000 rebounds and 1,200 assists in the first six seasons of their career. In the 85 games he played over the past two seasons, Towns launched seven threes per game and drilled 39.9% of them. That gravity is one reason why the Timberwolves have always, in every year of his career, had an elite attack when he plays and are significantly less efficient when he’s not in the game.

Towns, who averaged 24.8 points, 10.6 rebounds and 4.5 assists in 2020–21, wants to win.

David Sherman/NBAE/Getty Images

“I believe he’s a top-five talent in the league,” Finch says. “He’s got to be able to stay healthy, and we’ve gotta be able to continue to surround him with the right supporting cast.”

The Wolves ended last season 23–49, 13th in the West, despite having the same net rating as the Heat with Towns on the floor. But when he considers his future in basketball, there’s still excitement in his voice. While navigating the most difficult time of his life, Towns hasn’t lost sight of everything he wants to accomplish in a sport he’s still determined to dominate.

When the season first ended, Towns says he was lost, lamenting, among other things, an overseas family vacation he had planned before his mother died. “We were really gonna do a big world tour,” Towns says. “We hadn’t done a family vacation since I was in the second grade. Obviously, s— changed.”

So Towns spent the summer trying to work on himself. To self-interrogate. To let his anguish ebb and flow and run its course. He found himself searching for the right balance again, this time between self-care and assuming some of the responsibilities his mother held, which included being present for his grandmother, his aunts and his sister’s children. Jackie wasn’t only the head of her household. She looked after their extended family as the decision-making matriarch.

Then there were stretches where he just wanted to stay inside and do nothing except work out. He’d glance at a clock and realize it was midnight and that he hadn’t eaten anything all day.

But the offseason also provided some space to breathe. He didn’t have to worry about on-court performance, or leading the second-youngest roster in the league, or trying to establish a winning culture. The nightly pressures carried by a franchise player were replaced by the freedom to relax. Talks with his father and close friends helped. Towns leaned on his faith and went on trips with his girlfriend, Jordyn Woods. In Bora Bora, she would spot him on the beach, either head down in prayer or face-up, talking to the sky.

In early June, Rosas and Finch flew to Los Angeles and had dinner with Towns at Craig’s, a restaurant in West Hollywood. At a casual meeting that lasted about 90 minutes, they sat on the back patio, outside a packed dining room that, on this particular night, included Elton John. Over honey-truffle chicken and calamari, they watched Game 6 between the Lakers and Suns, where Towns’s close friend Devin Booker dropped 47 points. It doubled as a reminder that some of Towns’s contemporaries were passing him by. They didn’t discuss making a Finals run overnight, but were inspired by the Suns’ turnaround.

“Do you know how many times I’ve heard jokes about Phoenix? And then all of a sudden, boom, all together they said, ‘You know what? We’re gonna stop the bulls—. We’re gonna come together and we’re going to give everything to winning. No stats. No money. Just winning. And they went to the Finals,” Towns says. “So it’s a mentality. And it starts early.”

If they’re ever going to turn things around and make the playoffs, let alone flex some muscles once they arrive, it’ll be with a more balanced roster. Patrick Beverley and Taurean Prince were acquired during the offseason for that very reason, but finding ways to keep Towns engaged albeit out of foul trouble (he led the NBA in personal fouls in 2018 and ’19) when the Timberwolves don’t have the ball will be critical. Minnesota is tied for last in defensive rating since Towns was drafted.

“We gotta create a pick-and-roll scheme that helps him out and protects him in the best possible way,” Finch says. “And we gotta be able to protect the paint as a team, at the point of attack as a shell defense. And that’s going to help Karl out a lot. And I don’t think the Minnesota Timberwolves’ defensive struggles are Karl’s alone, or have been Karl’s alone.”

Entering his seventh season, Towns faces somewhat of an inflection point. “I think what’s really on the line is people’s perception of Minnesota. Of me,” he says. “I’m for sure not gonna fail. So I got to do what I got to do, but the pressure is high for me to win and rightfully so.”

Towns spent parts of the summer working out in L.A. with assistant coach Kevin Hanson and also split his time at the Proactive Sports Performance facility in Westlake Village. After he didn’t miss a single game in his first three seasons, he was derailed over the past two by injuries that included a sprained knee and a left wrist that’s been fractured and dislocated. His primary focus is to compete in all 82 again. Without good health, any other goal, team-wide or individual, can’t happen. He believes he’s in the best physical shape of his life.

One byproduct of that would be Towns reestablishing himself among the best centers in the league, after a season in which Jokić and Joel Embiid finished first and second for MVP, respectively. Looking at that debate, he believes championships will have a louder say in the discussion than anything else. “None of them won an NBA Finals, so all of us haven’t really accomplished anything,” Towns says. “We all chasing that title, that ring. That’s really what’s gonna set all of us apart. So that’s what I’m focused on. That’s what I’ve been focused on.”

Towns credits his mom for making basketball fun for him throughout his life.

David Sherman/NBAE/Getty Images

Finch believes Towns can compete at an All-Star level for the next decade. With three years left on his current contract, Towns would qualify for a supermax extension next summer by making an All-NBA team this year, a mutually beneficial possibility that would erase the stress of his looming free agency.

Towns has publicly committed to the Timberwolves several times, most recently at the end of the 2020–21 season, when he told reporters he wanted to have a career like Tim Duncan and Kobe Bryant, spending it all with one team. According to someone close to Towns, nothing related to that goal was altered in any meaningful way by Rosas’s dismissal. A contract extension is already on his radar.

“My chips are all on the table,” Towns says. “So it’s up to the Wolves, you know? If they give me the chance to stay there I fa’ sho would take it. The ball is in their court.”

When Jackie Towns died on April 13, 2020, it changed her son forever. He says he doesn’t smile as much, talks differently and doesn’t feel young the same way he did a couple of years ago. “I’m a totally different person,” Towns says. But life is also mapped by benchmarks that help signify change, and he’s starting to recognize the unforeseen blessings it can bring.

In February 2020, it was revealed that Towns fractured his left wrist. Not playing was hard, but the injury allowed him to leave the team and attend his niece’s birthday party, something he’d never been able to do because of his job. That party was the last time he saw his mom outside of a hospital. They talked and hugged. “I have a lot of memories of my mom that I hold very tight to me. And pictures that I would have never gotten if I wasn’t hurt,” he says.

“I’m a spiritual man. It’s kind of ironic how all that worked out. Like I was being prepared for something.”

Grief’s calendar is too unpredictable to let opening night of the 2021–22 NBA season be the exact moment Towns comes through on the other side of a dark period, fully healed. But time can be a passage to normalcy, and sometime over the last few months Towns noticed that his grief was starting to shrink as the strength to carry it began to swell. “I think I’ve grown as a person,” he says. “I had no choice. I think that I’m stepping into a new evolution of mine. Into a new evolution of me.”

In early September, Towns was sitting next to Woods when he made a spontaneous announcement.

“I was like, ‘You know what? I’m ready.’ ”

She had no idea what he was talking about, but Towns continued on.

“I’m like, ‘I’m ready. If we had to start today. I’m more than prepared. I’m mentally prepared to go to Minnesota, live in Minnesota, play this game of basketball.’ I’ve been working tremendously hard this offseason. I’ve been working on not only my body but just working on me.”

Towns pauses, looking for the words he’s spent the past 18 months trying to find. “I think I found some comfort in where my life is right now.”

• Paul Pierce Reflects on Hall of Fame Career

• How 9/11 Changed Life for Muslim American Athletes

• The Bucks’ Long Game Pays Off

[ad_2]

Source link