[ad_1]

On 29 February, Melissa Vanier, a 52-year-old postal worker from Vancouver, had just returned from holiday in Cuba when she fell seriously ill with Covid-19. “For the entire month of March I felt like I had broken glass in my throat,” she says, describing a range of symptoms that included fever, migraines, extreme fatigue, memory loss and brain fog. “I had to sleep on my stomach because otherwise it felt like someone was strangling me.”

By the third week of March, Vanier had tested negative for Sars-CoV-2 – the virus that causes Covid-19. But although the virus had left her body, this would prove to be just the beginning of her problems. In May, she noticed from her Fitbit that her heart rate appeared to be highly abnormal. When cardiologists conducted a nuclear stress test – a diagnostic tool that measures the blood flow to the heart – it showed she had ischaemic heart disease, meaning that the heart was not getting sufficient blood and oxygen.

Nicola Allan, a 45-year-old teacher from Liverpool, tells a similar story. Two months after first being diagnosed with Covid-19, she found her heart would start racing without warning. “It would get to 193 beats per minute,” she says. “It could be in the middle of the night or during the day. I would go white as a sheet, begin shaking and have to grab on to the walls for support. I’m now on beta blockers which have helped, but cardiologists still don’t understand why it happens.”

Both stories illustrate a wider trend – that the coronavirus can leave patients with lasting heart damage long after the initial symptoms have dissipated.

The first indications that Covid-19 could affect the heart came from the original centres of the outbreak. Peter Liu, chief scientific officer at the University of Ottawa Heart Institute, recalls receiving emails first from doctors in Wuhan during January and February, and then those in Italy as the pandemic reached Europe. They described a number of patients in intensive care wards with myocarditis or inflammation of the heart muscle.

“Because of my long-standing interest in how viral myocarditis can lead to heart failure, they asked me to participate in clinical data analysis to understand the impact of Covid-19 on the heart,” he says.

In March, the findings began to emerge. Of 68 patients who had died in one particular study, doctors reported that a third of these deaths had been caused by a combination of respiratory and heart failure. In a larger study, cardiologists at the Renmin hospital of Wuhan University found that of 416 patients, nearly 20% had cardiac injuries.

It wasn’t entirely unexpected that Covid-19 would lead to cardiovascular problems. Other viral infections such as Epstein-Barr virus and Coxsackievirus are known to be capable of causing heart damage ranging from mild to severe, while retrospective studies also found that both the Sars and Mers coronavirus outbreaks left some people with lasting heart complications. One 12-year follow-up of 25 Sars patients found that 11 (44%) still had long-term cardiovascular abnormalities when scans were taken.

Cardiologists say that Covid-19 has been different, both because of the much larger numbers of patients likely to be affected – there have been more than 32 million reported cases of Covid-19 as of 24 September, while Sars and Mers only affected 8,098 and 2,519 people respectively – and the greater extent of damage it leaves. It is thought that in some cases, the shortness of breath reported by Covid-19 patients may actually be due to damage to the heart rather than to the lungs.

“The original Sars virus did cause cardiac damage in a small proportion of patients. However, the extent of cardiac injury from Covid-19, as reflected by the release of biomarkers such as troponin in hospitalised patients, is surprising,” says Liu of the proteins that help regulate the contractions of the heart.

We now know that the Sars-CoV-2 virus gains access to the heart through enzymes called ACE2 and TMPRSS2, the biological locks it picks to slip into human cells. Because these enzymes are present across the body, in lung, heart, kidney, liver, gut and brain tissue, this allows the virus to move from one organ system to another. The fact that circulating ACE2 levels are higher in men than women is thought to be one of the reasons why men seem to be more vulnerable to Covid-induced heart problems.

Once inside the heart, the virus can inflict damage in a number of ways, either through directly invading heart cells and destroying them, or inducing an inflammatory response that can affect cardiac function. The stress on the body from fighting the virus can send the sympathetic nervous system – which directs the body’s response to dangerous or stressful situations – into overdrive, weakening the heart muscle. When scientists at the San Francisco-based Gladstone Institutes added the virus to human heart cells grown in a petri dish they were alarmed at the extent of the destruction. The long muscle fibres that keep the heart beating had been dissected into fragments, something also seen in autopsies of Covid-19 patients.

The impact of the virus can lead to conditions such as abnormal heart rhythms, cardiomyopathy – where the heart muscle tissue stiffens, making it harder to pump blood – and cardiogenic shock. In the most severe cases this results in heart failure.

Not everyone hospitalised with Covid-19 sustains heart injuries. Liu says that about a third of such patients show evidence of cardiac injuries on blood tests, and that of those who do, many will heal. For cardiologists, one of the key pieces of the puzzle is trying to understand who will recover, and who will not. In June, the British Heart Foundation announced six research programmes that are following hospitalised patients for six months, tracking damage to their hearts and circulatory systems.

Liu points out that, unsurprisingly, people who had cardiovascular problems prior to contracting Covid-19 are most vulnerable, as well as those with other underlying health conditions, such as kidney or liver disease. But the patient’s own immune response and the initial viral load they received also appear to be key factors. Raul Mitrani, a cardiac electrophysiologist at the University of Miami, says the amount of scarring a patient is left with plays a big role in determining the long-term prognosis.

“If there is inflammation, resulting in cardiac dysfunction, there is reasonable chance for recovery,” Mitrani says. “If cardiac cells die and are replaced by scar tissue, then herein lies the problem depending on what per cent of the heart is affected. If we see scarring, and especially if there is enough to impair cardiac function, we would worry about potential future heart failure and arrhythmias.”

For the second wave of Covid-19 patients admitted to hospital over the coming months, there is hope that the knowledge gained so far will enable doctors to take steps to mitigate the impact of the virus on the heart. Liu explains that steroids, which help dampen cardiac inflammation, are increasingly being used in advanced cases, while antivirals such as remdesivir may help by reducing viral load. Trials are also under way looking at whether angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) – commonly used to treat heart failure – can have a cardioprotective effect in high risk Covid patients.

However, in the past couple of months, new information has emerged that is particularly concerning for cardiologists – the suggestion that even people diagnosed with Covid-19 who have mild or no symptoms can be at risk of developing heart problems.

On 7 August, Michael Ojo, a professional basketball player for the Serbian club Crvena zvezda, collapsed during an individual training session in Belgrade. Ojo, 27, who had tested positive for Covid-19 in early July, had suffered a heart attack, and died shortly afterwards.

Ojo’s death was particularly mystifying because he appeared to have recovered from the virus. While he reported a cough, fever and chest pains in early July, a physical examination conducted on 5 August had indicated that he was well on the way back to full health.

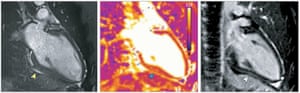

A week earlier, scientists at University Hospital Frankfurt’s Centre for Cardiovascular Imaging had published a notable study, using MRI scans to study the hearts of 100 patients who had contracted the virus in the spring and since recovered. While this group of people were relatively young – the average age was 49 – and mainly reported mild symptoms while they had Covid-19, the scans revealed that 78 of them had abnormal structural changes to their hearts. Whether these problems dissipate with time remains to be seen.

Since then, further evidence has emerged from Ohio State University of lingering heart inflammation in athletes who had the virus, almost all of whom experienced mild or no symptoms. While Saurabh Rajpal, a cardiologist at Ohio State University Medical Center, who led the study, emphasised that most cases resolve in a few weeks with no residual issues, the fact that some people have hidden, longer-term problems is concerning. In the case of the Frankfurt study, none of the patients involved suspected that anything might be amiss with their hearts when they had their scans.

The Ohio findings have already had implications in the sporting world. College sports leaders in the US announced that specific cardiac screening tests would now be required for any athletes that have previously tested positive.

“While there is active inflammation there is a chance of abnormal heart rhythms and, rarely, sudden death,” says Rajpal. “This risk of sudden death is higher in athletes while performing strenuous exercise. For athletes that develop myocardial inflammation, post-viral infection guidelines recommend rest for three months.”

Cardiologists are still trying to find out exactly why some people are left with enduring heart problems despite having had an apparently mild bout of Covid-19. The underlying mechanisms are thought to be slow and subtle changes that are quite different to those that put strain on the heart during the acute illness, especially in patients who have been hospitalised with the disease.

“At first, there is a small injury to the heart muscle, which is likely to occur during the acute stage of Covid, which triggers the slow evolution of diffuse muscular inflammation,” says Valentina Puntmann, a cardiologist involved in the Frankfurt study. “This takes a few weeks or months – and it is in most cases subclinical, so under the threshold of the current classification of cardiac symptoms. Given the subclinical course and evolution, the severity of this condition cannot be judged based on the symptoms. It is important to recognise that the injured heart needs time to heal.”

Some cardiologists have suggested that treatments such as cholesterol-lowering drugs, aspirin or beta blockers may help patients with lingering cardiovascular effects many weeks or months after the initial infection, but the evidence remains limited.

“It is too early to share data on this,” says Mitrani. “But these therapies have proven efficacy in other inflammatory heart muscle diseases. They have anti-inflammatory effects and we believe may help counter some of the lingering pro-inflammatory effects from Covid-19.”

But for patients such as Vanier, there remains a long and uncertain road to see whether her heart does fully recover from the impact of the virus. “Psychologically this has been brutal,” she says. “I haven’t been back to work since I went on holiday in February. The heart hasn’t improved, and I now have to wait for more tests to see if they can find out more.”

[ad_2]

Source link