[ad_1]

The woman is now a statistic, the rear end of a speeding ambulance, a lit pyre. The Sunday Express went to the Hathras village looking for the 19-year-old girl.(Express photo by Gajendra Yadav)

The woman is now a statistic, the rear end of a speeding ambulance, a lit pyre. The Sunday Express went to the Hathras village looking for the 19-year-old girl.(Express photo by Gajendra Yadav)

IT WAS a busy month on the sewing machine for the 19-year-old. On August 26, a baby was born, her brother’s third daughter. Apart from the usual embroidery work she did, the woman had to turn old dhotis and saris into clothes for the baby. Her hands worked fast on the machine, recalls her sister-in-law, “ekdum tez”.

Weeks later, the baby clothes lie unfinished. The sewing machine has been pushed to a corner and the swatches of fabric have been bundled onto a blue shelf in one of the three small rooms of the house in a village in UP’s Hathras.

Three weeks after the baby’s birth, her 19-year-old aunt was assaulted and allegedly raped by four upper-caste men in a bajra field that’s a five-minute walk from her house. Two weeks later, on September 29, the woman, born into one of the five Valmiki (Dalit) families in the village, died in a Delhi hospital — 201 km from her house, her mother, and her nieces.

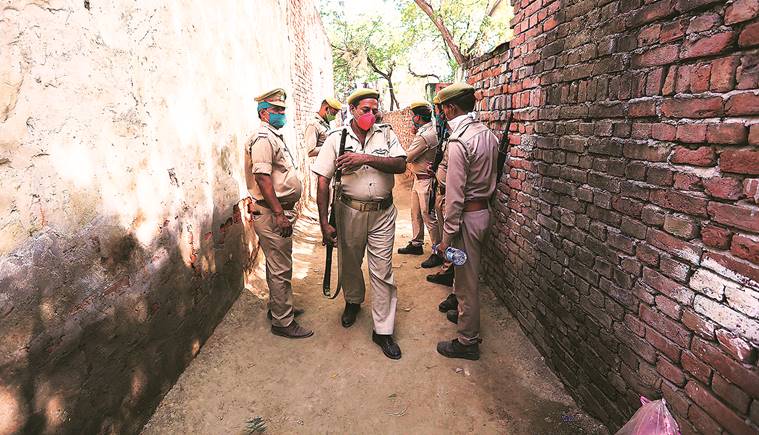

Policemen guard the 19-year-old victim’s home in the Hathras village; (top) the site of her hurried cremation. Gajendra Yadav

Policemen guard the 19-year-old victim’s home in the Hathras village; (top) the site of her hurried cremation. Gajendra Yadav

What followed the death was a surreptitious cremation done in the absence of family members, a village under siege by the police, allegations of threats by senior UP government officials, an Opposition on the roads, and the suspension of Hathras’s top police officers.

The woman is now a statistic, the rear end of a speeding ambulance, a lit pyre. The Sunday Express went to the Hathras village looking for the 19-year-old woman.

Born to agricultural labourers, the she was the fourth of five siblings. She was also the first woman in the family to attend school, briefly.

The village in Hathras district on UP after the rape incident, (Express photo by Gajendra Yadav)

The village in Hathras district on UP after the rape incident, (Express photo by Gajendra Yadav)

“She had to cross the highway just to get to the primary school. Trucks and buses moved at such speed… We pulled her out of school when she was in Class 5. We never let her go alone, we were afraid she might come under a car, or that someone might kidnap her… What we feared has come true. We couldn’t protect her,” says the woman’s mother, sobbing into her veil.

Opinion | Tavleen Singh writes: Hathras is a mirror in which we see the flaws of Indian democracy

On the morning of September 14, the mother says, the two of them had gone to the bajra fields to cut grass for their six buffaloes and cows. As the daughter worked a few metres away from the mother, she was allegedly dragged to a part of the field where she was allegedly gangraped and beaten up by Sandeep (20), Ravi (35), Luv Kush (23) and Ramu (26).

The mother says she found her daughter lying in a pool of blood, and the family rushed to a police station, followed by a local hospital. The woman was moved to a hospital in Aligarh, an hour away from the village, and then to Delhi’s Safdarjung Hospital on September 28. A day later, she died.

Flowers spread of the funeral pyre of the 19-year-old girl. (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav)

Flowers spread of the funeral pyre of the 19-year-old girl. (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav)

“A night before the incident, my daughter and I slept in the aangan, like we always did. She used to tell me every night how she can’t fall asleep unless I am next to her. Imagine my misfortune that I wasn’t allowed to see my daughter’s face when she died. How will I ever sleep peacefully now?” she says.

At 2.45 am Wednesday, from the small windows of its homes, a village shrouded in darkness and grief saw the smoke from a lonely pyre rise up into the sky as UP Police and the administration cremated the 19-year-old’s body, without the family.

Also Read | BJP IT head tweets her video; illegal if she’s rape victim, says NCW chief

“People say the family is brave… We are not brave. What option do we have? After the government deprived us of the right to carry out our sister’s last rites, fighting for justice is the only thing we can do,” says one of the woman’s cousins, sitting in her house that’s teeming with mediapersons Saturday afternoon.

A policeman roams around in the village. (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav)

A policeman roams around in the village. (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav)

A two-day siege, with 300 UP Police personnel guarding every inch of the village, was lifted Saturday morning. With reporters camping outside the village for days, and news of her death making global headlines, the spotlight is suddenly on the small village and its 60 families. Of these, only about five households are of Valmikis, while the rest are of Brahmins and Thakurs.

A dirt track separates — or joins — the victim’s home and that of the accused. But the events of the last few weeks have turned old fault lines into deep, cavernous divides.

Also Read | Damage control in Hathras: UP Govt seeks CBI probe, lifts village lockdown

“She’s ruined our village’s name… brought such disrepute. Who will marry their daughters into this village now?” says a Thakur resident of the village.

At the victim’s home, a cousin says that despite the siege, he is aware of the “rumours”. “If the SP can go on national TV and say she was not raped, what can one expect from the Thakurs of the village, who are convinced she lied. She gave a statement, why would she lie?”

The funeral pyre of the Hathras victim, hours later. (Express photo: Amil Bhatnagar)

The funeral pyre of the Hathras victim, hours later. (Express photo: Amil Bhatnagar)

The woman’s sister-in-law says that like most women in the village, the 19-year-old mostly stayed at home. Even the rare visits to the market didn’t always end well, she says. “She would come back angry… say the upper-castes say mean things about us, called her names… and so on,” says the sister-in-law.

The year the woman was born, “a few days before wheat was harvested in 2001”, Sandeep’s grandfather had spent time in jail for allegedly beating up the woman’s grandfather. “He broke his head with a hammer, a case was filed… Since then, this family has had a problem with us. They use caste-based slurs, the accused also threatened her in the past,” says a family member of the 19-year-old.

For two days as the siege went on, police took over the village’s fields, rooftops and lanes. With Section 144 of CrPC in place, most residents didn’t leave their homes.

Members of the Ajad Samaj party and Bhim army burns effigy of UP Chief Minister in Ludhiana. Express Photo by Gurmeet Singh.

Members of the Ajad Samaj party and Bhim army burns effigy of UP Chief Minister in Ludhiana. Express Photo by Gurmeet Singh.

Also locked in was the 19-year-old’s family. On Saturday, when police lifted the blockade, the media thronged the small brick house, occupying every conceivable inch of space in each of the rooms with mics and questions. “We haven’t eaten all day, the children are soaking biscuits in water for lunch. Give us some space,” the victim’s sister-in-law says, overwhelmed.

The arrival of the 19-year-old’s niece in August had brought the family together for the first time in over a year. The woman’s two married sisters and their children had paid a visit.

“We all got together before bhabhi’s delivery, hoping it would be a boy after two girls. Par phir se ladki hui (But it was a girl again)…,” says the victim’s elder sister.

Samajwadi Party women wing workers clash with police personnel during their protest over the death of a Dalit woman from Uttar Pradesh’s Hathras, who was gang-raped on Sept. 14, in Lucknow, Tuesday. (PTI)

Samajwadi Party women wing workers clash with police personnel during their protest over the death of a Dalit woman from Uttar Pradesh’s Hathras, who was gang-raped on Sept. 14, in Lucknow, Tuesday. (PTI)

It was the 19-year-old, says the sister-in-law, who convinced the family to celebrate the baby’s arrival. “She was the only one who said it’s a happy moment, that the baby has continued their tradition of three sisters in the family. I sometimes wonder, how did she get so wise?” she says.

In the house teeming with relatives and outsiders, the baby moves from one lap to another.

Also Read | Hathras rape case: Under fire, UP Govt suspends SP, orders narco test of accused, victim families

The sister-in-law says that with women in the village mostly confined to their homes, the 19-year-old had grown to become her best friend. “She was only 14-15 when I got married and came here. Such a baby. She still sucked her thumb while sleeping, her one hand on her eyebrow,” she says, laughing.

As she grew older, the 19-year-old became the one the sister-in-law would turn to when in trouble. “She would advise me on how to tackle marital issues, how not to get angry over petty problems at home, how to always wear the ghoonghat… This is how it is in villages, girls grow up very quickly,” says the sister-in-law.

Hathras gangrape: Policemen at the victim’s village, a day after her cremation. (Express photo by Gajendra Yadav)

Hathras gangrape: Policemen at the victim’s village, a day after her cremation. (Express photo by Gajendra Yadav)

A day after the 19-year-old’s hurried cremation, a video had surfaced of the sister-in-law chasing a UP government official’s vehicle in the village. “I can’t eat or sleep… Look at what we have been put through. We might be poor, we might be Dalits but do we have no right over a loved one? They didn’t even let us see her off peacefully,” she adds.

In a village where most lips are sealed, where questions about the woman are either met with “woh bahut bholi thi (she was very innocent)” or that “she is lying” — depending on who you talk to — it’s hard to know what it is to be a 19-year-old growing up in a Dalit home in a UP village, where multiple fault lines run into each other. Of caste, gender, and countless others.

Who was this 19-year-old? From the family’s accounts, she is someone who made the “perfect rotis”, whose world revolved around her nieces, who rarely left her home and depended on her brother, a wage labourer, to bring back “ladkiyo wala samaan” from the market for her. Yet, in the hours after her death, as politicians put out her videos doubting the veracity of her statement, her real story, her version of events, will remain unsaid.

Candlelight vigil organised by Congress, in Mumbai on Friday. (Photo by Ganesh Shirsekar)

Candlelight vigil organised by Congress, in Mumbai on Friday. (Photo by Ganesh Shirsekar)

What is confirmed, though, is a life snatched away at 19, and a mother’s loss.

The mother says, “The last time I spoke to her was when she was in Aligarh hospital. She told me she missed me, her nieces, that she wanted to come back home. Even when she was in so much pain, she inquired about my health, asked if her nieces were eating well.”

The mother says she hasn’t mustered the courage to go to the spot where the 19-year-old’s ashes still lie, unclaimed.

“When I would complain about our struggles, poverty, she would always say that things would get better some day. How can there be better days with her gone at such a young age… And like this?”

📣 The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest India News, download Indian Express App.

© The Indian Express (P) Ltd

[ad_2]

Source link