[ad_1]

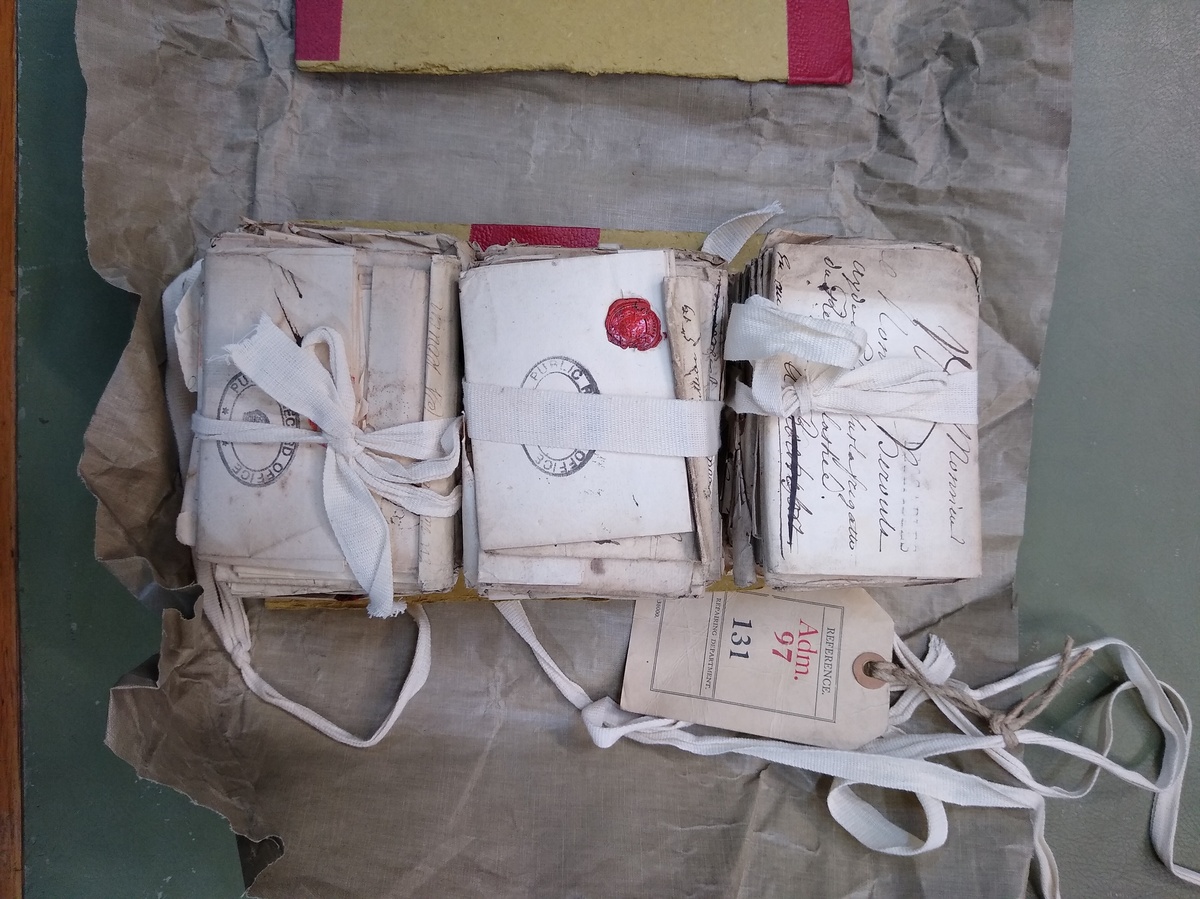

The letters earlier than they had been opened.

The National Archives/Renaud Morieux

conceal caption

toggle caption

The National Archives/Renaud Morieux

The letters earlier than they had been opened.

The National Archives/Renaud Morieux

Scores of French love letters from the mid-18th century have been opened and studied for the primary time since they had been written.

The letters – despatched to French sailors by wives, siblings and fogeys – by no means made it to their supposed recipients, however they provide uncommon perception into the lives of households affected by struggle.

“I could spend the night writing to you,” wrote Marie Dubosc to her husband. “I am your forever faithful wife. Good night, my dear friend. It is midnight. I think it is time for me to rest.”

Dubosc wouldn’t have identified her husband had been captured by the British, and that he would by no means obtain her message. She died the yr after she despatched the letter, and sure by no means noticed him once more.

Sent between 1757-58 in the course of the Seven Years War, the letters had been largely addressed to the crew of the Galatée warship, and the French postal administration forwarded them from port to port in hopes of reaching the sailors. But when the British Navy captured the Galatée in April 1758, French authorities forwarded the batch of letters to England.

There they remained unopened for hundreds of years, till the historian Renaud Morieux of the University of Cambridge found them within the digital stock of Britain’s National Archives. He checked out the field from the archives with no concept what he would discover inside.

The field got here with three packs of letters wrapped in white ribbon.

“I had to basically pull the string a bit like a Christmas gift,” he informed NPR.

“My heart started to beat faster and I felt like, ‘Ooh, this looks like really cool stuff…There might be some secrets in there.'”

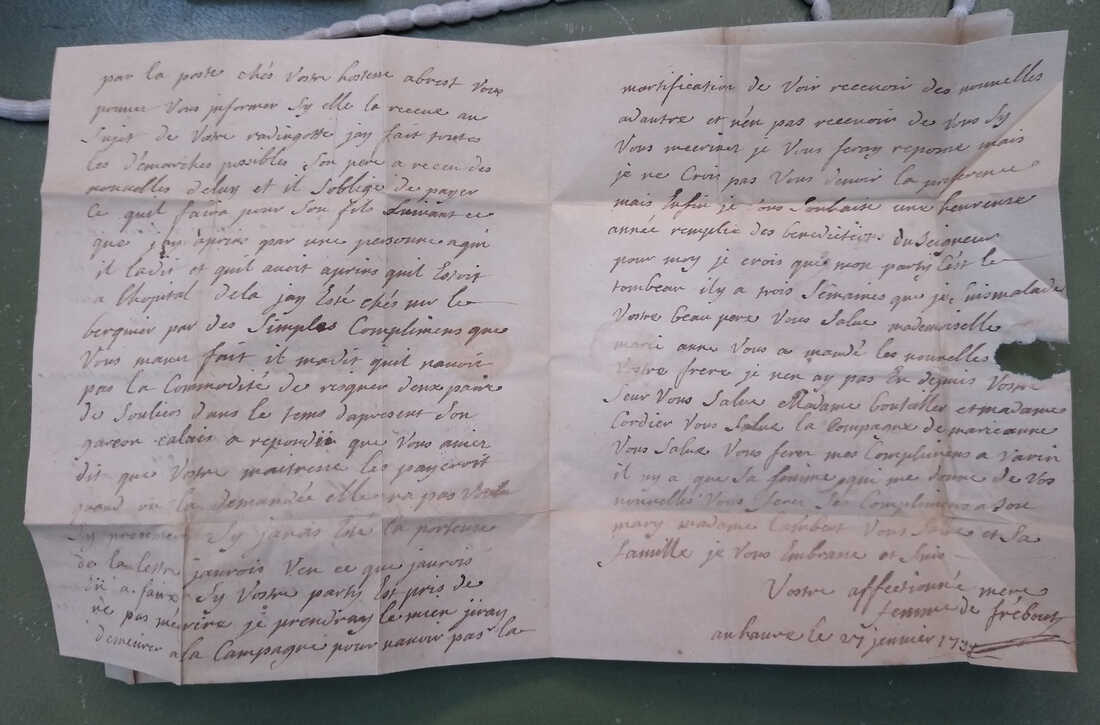

Anne Le Cerf’s love letter to her husband Jean Topsent during which she says “I cannot wait to possess you” and indicators “Your obedient wife Nanette.”

he National Archives/Renaud Morieux

conceal caption

toggle caption

he National Archives/Renaud Morieux

Anne Le Cerf’s love letter to her husband Jean Topsent during which she says “I cannot wait to possess you” and indicators “Your obedient wife Nanette.”

he National Archives/Renaud Morieux

The 104 letters are written on heavy, costly paper, and a few have crimson wax seals. But they comprise the phrases of widespread individuals somewhat than aristocrats, Morieux says – voices typically lacking from the historic report, like sailors’ and fishermens’ wives.

“These letters tell us about how people from the lower classes dealt with the challenges of war and the absence of their kin and loved ones,” Morieux says, “and how they managed to overcome distance and the fear of uncertainty.”

Morieux spent months decoding the letters, and revealed his findings Monday within the French historical past journal Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales.

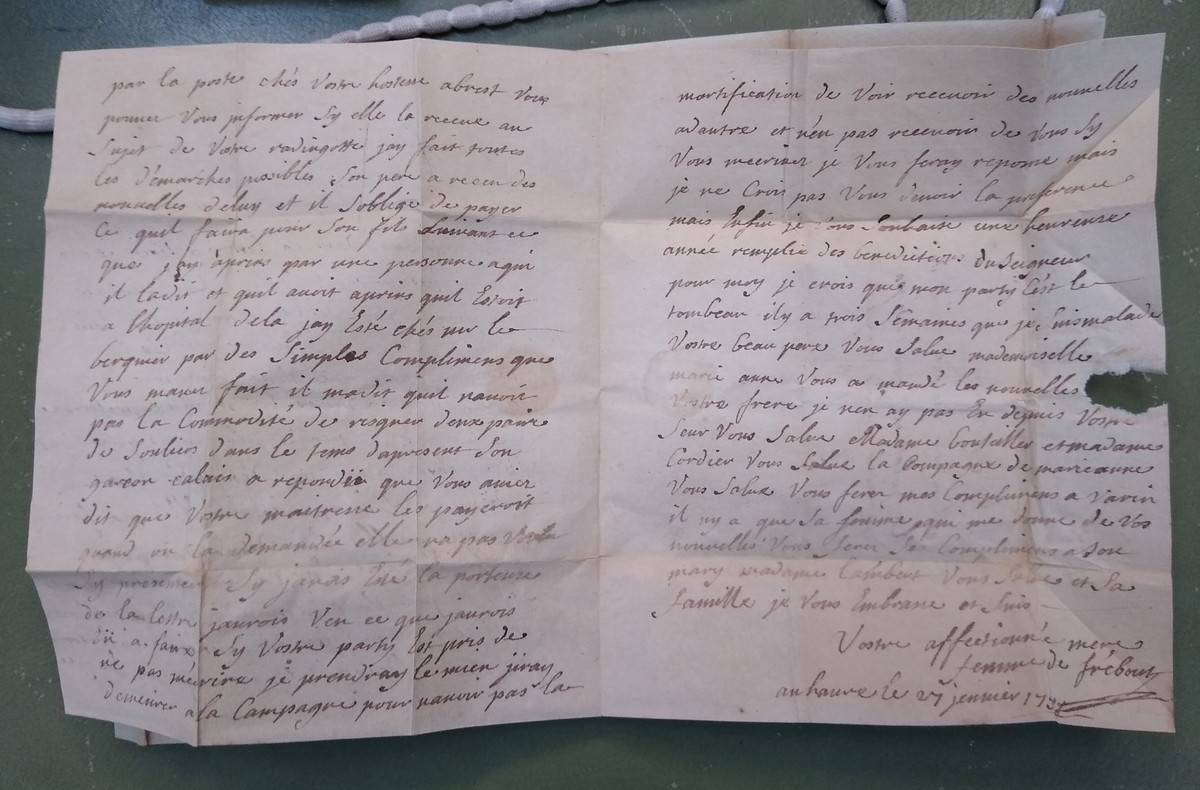

In one letter, Marguerite Lemoyne, a 61-year-old mom, scolds her son Nicolas Quesnel for not writing:

“On the first day of the year [i.e. January 1st] you have written to your fiancée… I think more about you than you about me…In any case I wish you a happy new year filled with blessings of the Lord. I think I am for the tomb, I have been ill for three weeks. Give my compliments to Varin [a shipmate], it is only his wife who gives me your news.”

Marguerite’s letter to her son Nicolas Quesnel (dated Jan. 27, 1758), during which she says, “I am for the tomb.”

The National Archives/Renaud Morieux

conceal caption

toggle caption

The National Archives/Renaud Morieux

Marguerite’s letter to her son Nicolas Quesnel (dated Jan. 27, 1758), during which she says, “I am for the tomb.”

The National Archives/Renaud Morieux

Morieux informed NPR Lemoyne’s grievance reveals “universal” household dynamics.

“The son who’s at sea is only writing to his fiance, and the mother gets really pissed off about that,” Morieux mentioned. “And here you feel that there is some kind of…really long, ancient trope about tensions in the family between the mother and the daughter-in-law.”

Morieux mentioned the letters additionally reveal the issue of long-distance communication within the 1750s. Many of the senders, like Lemoyne, had been seemingly illiterate and dictated their messages to a scribe.

Moreover, sending a letter to a ship consistently on the transfer throughout wartime was troublesome and unreliable, and households typically despatched a number of copies of letters to totally different ports.

In an effort to maximise the probabilities of efficiently speaking with a beloved one, every letter had a number of messages crammed onto the paper, typically from totally different households and addressed to a number of crewmates.

“And so they’re covered with ink, not just from top to bottom…The sentences are written from left to right, but also they’re written in the margins,” Morieux mentioned.

To Morieux, the letters present how communities keep resilient in occasions of disaster.

“It’s about the power of the collective. It’s about how these people can only survive by relying on others.”

Christopher Intagliata and Gabriel Sanchez contributed to this report.

[adinserter block=”4″]

[ad_2]

Source link