[ad_1]

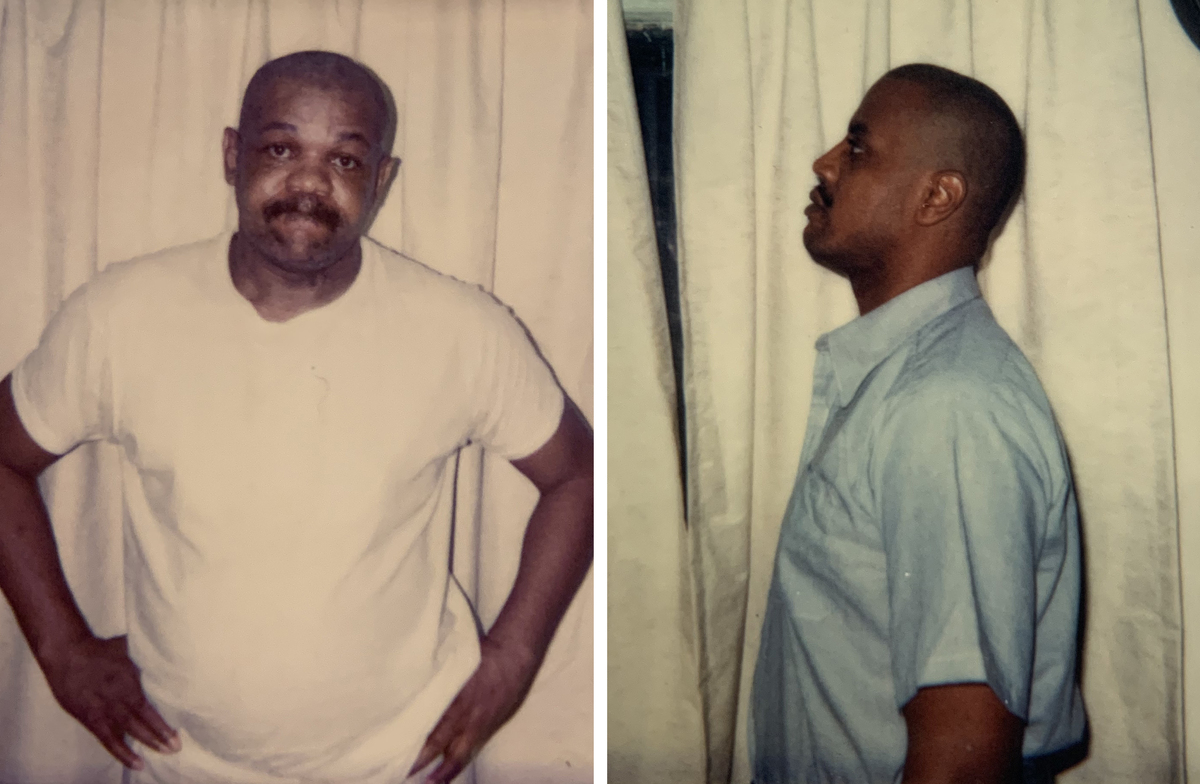

Wilbert Lee Evans (left) and Alton Waye have been executed in 1990 and 1989. NPR obtained tapes that recorded their deaths. You can hear them beneath.

Library of Virginia

disguise caption

toggle caption

Library of Virginia

Wilbert Lee Evans (left) and Alton Waye have been executed in 1990 and 1989. NPR obtained tapes that recorded their deaths. You can hear them beneath.

Library of Virginia

On a summer season’s day in 2006, inside an condominium not removed from Virginia’s outdated demise chamber, an 82-year-old man handed over a briefcase to an archivist. The bag held 4 execution recordings so uncommon, related tapes from one other state had been launched simply as soon as earlier than in historical past.

When executions happen, only some individuals are permitted to attend as witnesses. Since prisons forbid even these journalists, attorneys and relations from recording audio or photos, just about no bodily proof from their vantage level exists from any state. But they don’t seem to be the one ones watching. Prison workers additionally see what occurs within the demise chamber – and so they generally tape it.

The cassettes within the briefcase have been recorded by employees, and the donor, R. M. Oliver, had labored in Virginia prisons for years. But how that authorities audio ended up in his bag – and why he privately donated it to the Library of Virginia – is a thriller. Oliver left his final place with the Department of Corrections in Richmond earlier than any of the executions have been taped. His household stated he took the story to his grave when he died.

The 4 tapes have been marked as “restricted” within the archives of the Library of Virginia in Richmond.

Chiara Eisner/NPR

disguise caption

toggle caption

Chiara Eisner/NPR

The 4 tapes have been marked as “restricted” within the archives of the Library of Virginia in Richmond.

Chiara Eisner/NPR

“Dad kept it a secret from us,” stated his son, Stephen Oliver. “I don’t even remember seeing that briefcase.”

The tapes from Oliver’s bag remained unavailable for 16 years. The library initially restricted them and deliberate to maintain them off limits for many years extra. But NPR argued for his or her public launch and obtained the audio in 2022.

An NPR investigation can now reveal the tapes present the jail uncared for to document key proof throughout what was thought-about certainly one of Virginia’s worst executions, and employees appeared unprepared for a few of the jobs they have been tasked to do within the demise chamber.

Before Virginia abolished capital punishment in 2021, the state executed extra folks than every other in America. This is the primary time audio recorded throughout any of these executions has ever been revealed.

Behind the scenes: “We didn’t know for sure”

Minutes earlier than he was scheduled to die by the electrical chair, Alton Waye used his final phrases to forgive the employees who would quickly need to help kill him.

“I’d like to express that what is about to occur here is a murder,” he begins by saying on the tape.

An worker whispers the remainder of Waye’s assertion into the recorder: “And that he forgives the people involved in this murder. And that I don’t hate nobody and that I love them.”

That employee then checked in with one other colleague to see if he had heard the assertion accurately. He hadn’t.

“I’m trying to get it,” the second man responds. “I would like to express that what is about to take place here is a murder. Did anyone else catch the rest of that?”

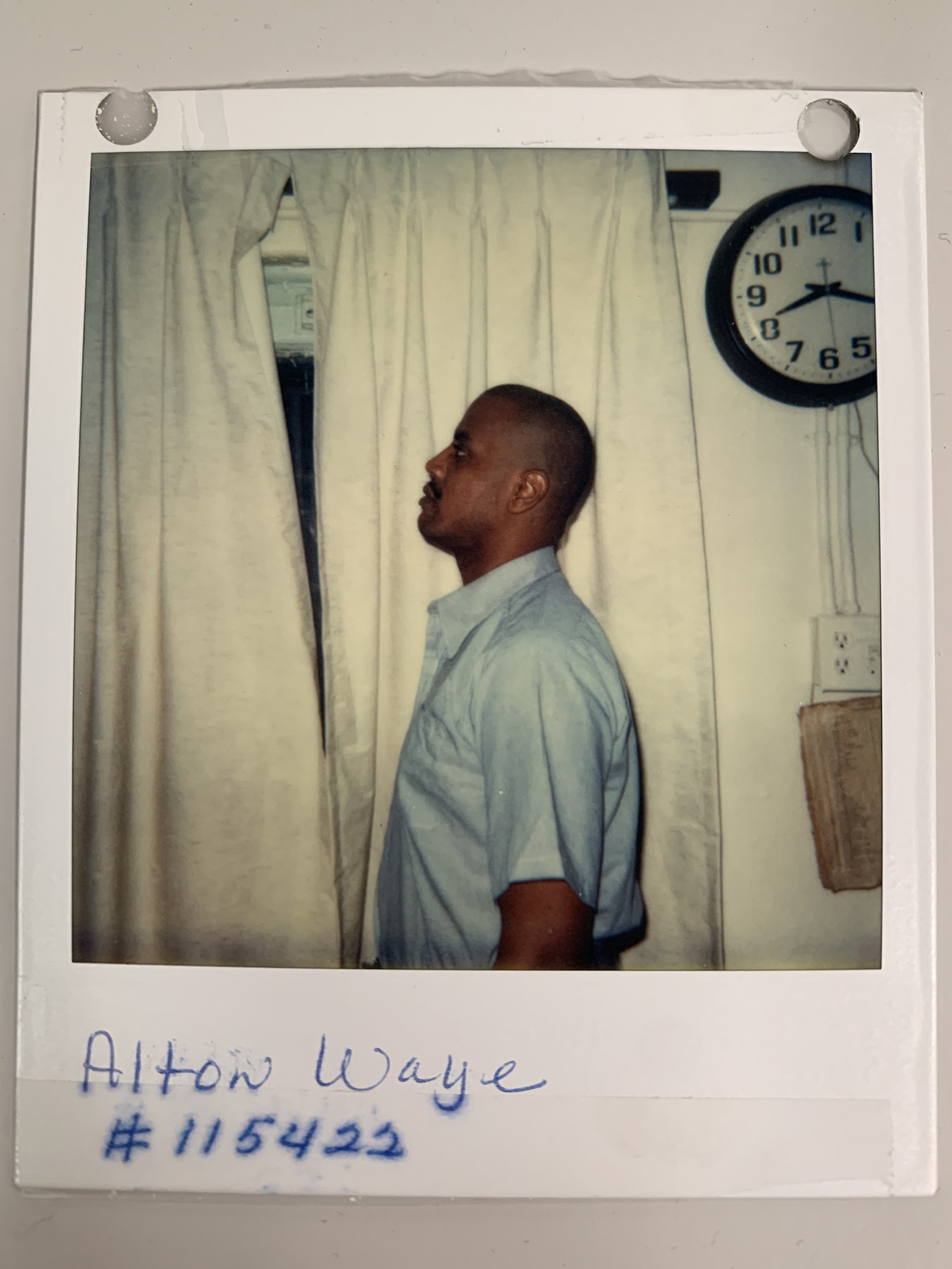

Oliver’s briefcase additionally contained different official execution paperwork from the jail, like this photograph of Alton Waye that was taken earlier than he was executed in 1989.

Library of Virginia/Chiara Eisner/NPR

disguise caption

toggle caption

Library of Virginia/Chiara Eisner/NPR

Oliver’s briefcase additionally contained different official execution paperwork from the jail, like this photograph of Alton Waye that was taken earlier than he was executed in 1989.

Library of Virginia/Chiara Eisner/NPR

The jail ultimately bought Waye’s phrases down proper. But the opposite tapes present uncertainty was frequent within the demise chamber. At the start of the narration of Richard Whitley’s execution in 1987, the employees appeared confused about how they have been presupposed to document the occasion.

“We’re not using a blank tape?” one employee asks, earlier than a second wonders out loud if the recorder was turned on.

The jail employees appeared nonetheless extra unprepared throughout the electrocution of Richard Boggs. For greater than two minutes, employees could be heard on the tape showing to battle to attach a name from one of many solely folks with the ability to cancel an execution on the final second.

“We need to get 306 clear, the governor’s office is calling,” a employee says.

The scenario was pressing.

“Debbie, they are strapping him in the chair!” a second lady exclaims. “Hold on a minute.”

If the governor needed to avoid wasting Boggs’ life, he would must be linked with somebody within the demise chamber rapidly. Minutes handed, nevertheless, and the problem appeared unresolved. A 3rd worker predicted they must lower Debbie off so as to join the governor.

“Let me call Switchboard and see what’s going on,” one of many staff interjects, earlier than a line seems to go lifeless.

Boggs was ultimately executed. The governor, L. Douglas Wilder, had not known as to spare him. But if Wilder had felt in a different way – and had the employees not been in a position to join him in time – Virginia might have come near finishing up the execution of a pardoned man.

“We didn’t know for sure whether you had contact down there with the governor’s office,” one of many staff reiterates on the tape.

The fourth and closing recording revealed a extra severe oversight.

Bloody proof, hidden on document

Local reporters who watched the execution of Wilbert Lee Evans in 1990 stated they witnessed one of many worst in Virginia’s historical past. Three journalists wrote within the Richmond Times-Dispatch that, following the administration of the primary jolt of electrical energy from the chair, Evans began to bleed from his eyes, mouth and nostril.

A polaroid photograph of Wilbert Lee Evans was taken earlier than he was executed in 1990.

Library of Virginia/Chiara Eisner/NPR

disguise caption

toggle caption

Library of Virginia/Chiara Eisner/NPR

A polaroid photograph of Wilbert Lee Evans was taken earlier than he was executed in 1990.

Library of Virginia/Chiara Eisner/NPR

“Blood flowed from under the leather death mask,” noticed a journalist from the Virginian-Pilot.

A reporter from a 3rd newspaper, the Alexandria Journal, stated one thing related.

“He started bubbling blood,” Geoff Brown noticed, “and it ran down his belly and his shirt.”

But the tape the jail created throughout Evans’ execution recorded none of these particulars.

“It is 11:04, the first surge of electricity has been administered,” an worker states.

It was proper after that first jolt that reporters stated the blood began streaming down Evans’ chin and soaking his shirt. The voice of the narrator could be heard breaking on tape. But if she was affected by the scene, she did not make clear the rationale. She by no means talked about any proof of blood.

“It is 11, 11:05,” she stutters. “The second surge of electricity has been administered.”

Then, minutes later, simply: “The inmate has expired.”

“What is the state trying to cover up?”

None of the 27 states that at the moment enable the demise penalty use the chair as their main methodology of execution anymore. Most have switched to deadly injection. But errors within the demise chamber are nonetheless frequent.

In 2022, greater than a 3rd of the 20 executions that have been tried throughout the nation were botched. The governor of Tennessee known as off an execution after he discovered employees had failed to check the chemical compounds they have been planning on utilizing for contamination. Workers in Texas struggled for greater than half an hour to position an IV right into a disabled man’s neck.

Official cowl ups after the executions go fallacious are additionally commonplace. Behind closed doorways, on July 28, 2022, execution staff in Alabama took greater than three hours to set an IV line into Joe James, Jr.’s physique. The state stated nothing out of the bizarre occurred throughout that point. But a nonprofit, Reprieve, obtained permission from his household to conduct an post-mortem afterwards. It revealed a number of puncture wounds, bruises, and proof that the state could have lower into his pores and skin to discover a vein, stated Blaire Andres, who leads demise penalty tasks for Reprieve.

The Alabama Department of Corrections supplied this undated photograph of Joe Nathan James, Jr. to the press.

Alabama Department of Corrections through AP

disguise caption

toggle caption

Alabama Department of Corrections through AP

The Alabama Department of Corrections supplied this undated photograph of Joe Nathan James, Jr. to the press.

Alabama Department of Corrections through AP

“All of that was hidden from view from the journalists that were supposed to witness the execution,” stated Andres. “If the state is doing everything correctly, they shouldn’t have anything to hide. So it does raise the question, what is the state trying to cover up?”

The Alabama Department of Corrections didn’t reply to NPR’s request for remark. The similar query now stays open in Virginia, too. Though the library ultimately launched the tapes Oliver donated, NPR found the Department of Corrections has extra audio that it is nonetheless selecting to maintain hidden from the general public.

After NPR requested all remaining execution audio from the company below the Freedom of Information Act, Corrections confirmed it has a minimum of six extra audio recordsdata with 70 minutes of tape recorded on them. But it refused to share the tapes. It additionally declined an interview request.

In an e mail, a consultant from the company defended the choice to maintain the audio hid. Because the tapes are personal jail data, personal well being data and comprise confidential personnel info, the company doesn’t need to share them, the consultant wrote.

An legal professional who teaches on the University of Virginia’s legislation faculty, Ian Kalish, reviewed the e-mail. He stated Corrections gave the impression to be appearing in a fashion opposite to the intention of the state’s public data legislation, which was designed to grant folks entry to authorities recordsdata.

Left: The electrical chair within the demise chamber at Virginia State Penitentiary in 1991. Right: The pc that managed the electrical chair. The jail was closed and demolished within the early ’90s.

Library of Virginia

disguise caption

toggle caption

Library of Virginia

Left: The electrical chair within the demise chamber at Virginia State Penitentiary in 1991. Right: The pc that managed the electrical chair. The jail was closed and demolished within the early ’90s.

Library of Virginia

“These types of records are really key to facilitating public oversight and holding public bodies and government actors accountable,” Kalish stated. “It’s very concerning to me that this type of information is being withheld.”

As lengthy as Corrections refuses to disclose the remainder of the execution audio, Oliver’s tapes may very well be the one present content material from inside Virginia’s demise chamber that folks can hear. Together with the 19 execution tapes from Georgia that an legal professional subpoenaed throughout a court docket case, the 2 units are the one items of publicly out there audio proof from the greater than 1,500 executions which have taken place throughout the U.S. throughout the previous 50 years.

Whether Oliver knew how vital the 4 tapes can be when he gave them away is unclear. But Roger Christman, the archivist who collected the briefcase from Oliver’s condominium again in 2006, thinks he could have had an concept.

“He was really happy that he could find a home for these records,” Christman remembered. “He thought they were very important.”

Barrie Hardymon edited this story. Monika Evstatieva produced it.

[adinserter block=”4″]

[ad_2]

Source link