[ad_1]

Image copyright

Image copyright

Getty Images

How was an Indian elected to the British Parliament in 1892? What relevance could this historical event have for us today?

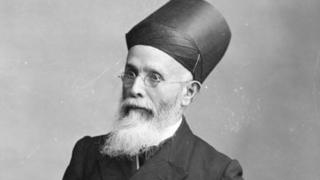

Dadabhai Naoroji (1825-1917) is an unfamiliar name these days.

Yet, aside from being the first Asian to sit in the House of Commons, he was also the most important leader in India before Mahatma Gandhi, as well as being an anti-racist and anti-imperialist of global significance.

Now, more than ever, amidst various global crises, he deserves to be remembered.

His life is a stirring testament to the power of progressive politics – and how the determined pursuit of such politics can bring light into even the darkest chapters of history.

Naoroji was born into relative poverty in Bombay. He was an early beneficiary of a novel experiment – free public schooling – and believed that public service was the best way to repay his moral debts for his education.

From an early age, he championed progressive causes that were deeply unpopular.

In the late 1840s, he opened schools for Indian girls, earning the wrath of orthodox Indian men. But he had a knack of persevering and turning the tide of opinion.

Within five years, girls’ schools in Bombay were brimming with pupils. Naoroji responded by setting the bar higher, making an early demand for gender equality. Indians, he argued, would one day “understand that woman had as much right to exercise and enjoy all the rights, privileges, and duties of this world as man.”

In 1855, Naoroji made his first visit to Great Britain.

He was utterly stunned by the wealth and prosperity he saw and began reflecting on why his own country remained so impoverished.

Thus began two decades of path-breaking economic analysis whereby Naoroji challenged one of the most sacred shibboleths of the British Empire: the idea that imperialism brought prosperity to colonial subjects.

Image copyright

Courtesy: Dinyar Patel

Naoroji was nearly 90 years old when he met with the Irish-Indian nationalist Annie Besant

In a torrent of scholarship, he proved that the exact opposite was true.

British rule, he argued, was “bleeding” India to death, unleashing catastrophically deadly famines. Many enraged Britons, hurling charges of sedition and disloyalty, could barely believe that a colonial subject could make such claims in public.

Others, however, benefitted from Naoroji’s foundational contributions to anti-colonial thought.

His idea of how imperialism caused a “drain of wealth” from colonies informed European socialists, American Progressives like William Jennings Bryan, and possibly even Karl Marx. Slowly, as with female education in India, Naoroji helped turn the tide of public opinion.

Indian poverty, of all things, was the launching pad for Naoroji’s parliamentary ambitions.

As a British colonial subject, he could stand for Parliament, as long as he did so from Britain.

Following the model of some Irish nationalists, he believed that India should demand political change from within the halls of power in Westminster: there were no similar avenues in India. And so, in 1886, he launched his first campaign, from Holborn, and was soundly defeated.

He did not give up. Over the next few years, he forged alliances between Indian nationalism and a host of progressive movements in Britain. Naoroji also became a vocal supporter of women’s suffrage.

He championed Irish home rule and nearly stood for Parliament from Ireland. And he aligned himself with labour and socialism, critiquing capitalism and calling for sweeping workers’ rights.

Through sheer perseverance, Naoroji convinced a widening spectrum of Britons that India required urgent reform – just as women deserved the vote, or workers an eight-hour day. He received letters of support from workmen, union leaders, agriculturalists, feminists, and clergymen.

Image copyright

COURTESY: DINYAR PATEL

Naoroji’s receipt for membership dues to the Women’s Franchise League in UK

Not all Britons were pleased with the prospective Indian MP. He was tarred as a “carpetbagger,” and “Hottentot.”

No less than the British prime minister, Lord Salisbury, derided Naoroji as a “black man” undeserving of an Englishman’s vote.

But he convinced just enough of his target audience.

In 1892, voters in Central Finsbury in London elected him to Parliament by a margin of five votes (thereafter dubbing him Dadabhai Narrow-majority).

Dadabhai Naoroji, MP, lost little time making his case in Parliament.

He proclaimed British rule to be “evil,” a force that made his fellow Indians no better than slaves. He championed legislation to transform the colonial bureaucracy and put it in Indian hands.

All of this came to naught. MPs mostly ignored his pleas and Naoroji lost re-election in 1895.

This was Naoroji’s darkest hour.

In the late 1890s and early 1900s, as British rule grew more draconian, and as famine and a plague epidemic killed millions in the subcontinent, many Indian nationalists believed that their cause was at a dead end.

Somehow, Naoroji maintained his optimism. He embraced more progressive constituencies – early Labourites, American anti-imperialists, African-Americans, and black British activists – while augmenting his demands.

India, he now declared, needed self-rule or swaraj, the only antidote to the colonial drain of wealth.

Swaraj, he told the British prime minister, Henry Campbell-Bannerman, would serve as “reparation” for imperialist wrongdoing.

A poster of Naoroji’s support for trade unions

These words and ideas reverberated around the globe: they were picked up in European socialist circles, the African-American press, and by a band of Indians in South Africa led by Gandhi.

Swaraj was an audacious demand: how could a downtrodden people wrest authority from the most powerful empire in human history?

Naoroji retained his characteristic optimism and never-say-die attitude.

In his last speech, delivered when he was 81 years old, he acknowledged the disappointments he had faced in his political career – “disappointments as would be sufficient to break any heart and lead one to despair and even, I am afraid, to rebel”.

However, perseverance, determination, and faith in progressive ideas were the only true options. “As we proceed,” he told members of the Indian National Congress, “we may adopt such means as may be suitable at every stage, but persevere we must to the end.”

How might such words inform today’s political debates?

Over a century later, Naoroji’s sentiments might seem naïve – a quaint anachronism in an era of populism, ascendant authoritarianism, and sharp partisanship.

Our times are starkly different.

The current crop of Asian MPs in the British Parliament, after all, includes recalcitrant Brexiteers with muddled perspectives on Britain’s imperial history.

India is in the grips of Hindu nationalism that is entirely at odds with its founding principles – principles that Naoroji helped to craft.

Image copyright

courtesy: dinyar patel

A Punch cartoon depicting Naoroji confronting Lord Salisbury

It is impossible to imagine what Naoroji, who advanced his political agenda through detailed scholarship and patient study, would make of a world adrift in fake news and alternative facts.

And yet, perseverance, persistence, and faith in progress, the hallmarks of Naoroji’s career, can offer a way forward.

When Naoroji began publicly demanding swaraj in the early 1900s, he believed that its achievement would take at least 50 to 100 years.

Britain was at its imperial zenith, and most Indians were too starved and poor to consider lofty ideas like self-government.

He would have been stunned to realise that his grandchildren lived in a free India and witnessed, from afar, the death throes of the British Empire.

Thus, some important lessons: empires fall, autocratic regimes have finite lifespans, popular opinion turns suddenly.

The forces of right-wing populism and authoritarianism might be ascendant today, but Naoroji would counsel us to take a long-term perspective.

He would urge us to maintain faith in progressive ideals and, above all, to persevere.

Perseverance and steely determination can yield the most unexpected results – far more unexpected than an Indian winning election to the British Parliament over a century ago.

Naoroji: Pioneer of Indian Nationalism was published in May 2020 by Harvard University Press and HarperCollins India.

[ad_2]

Source link