[ad_1]

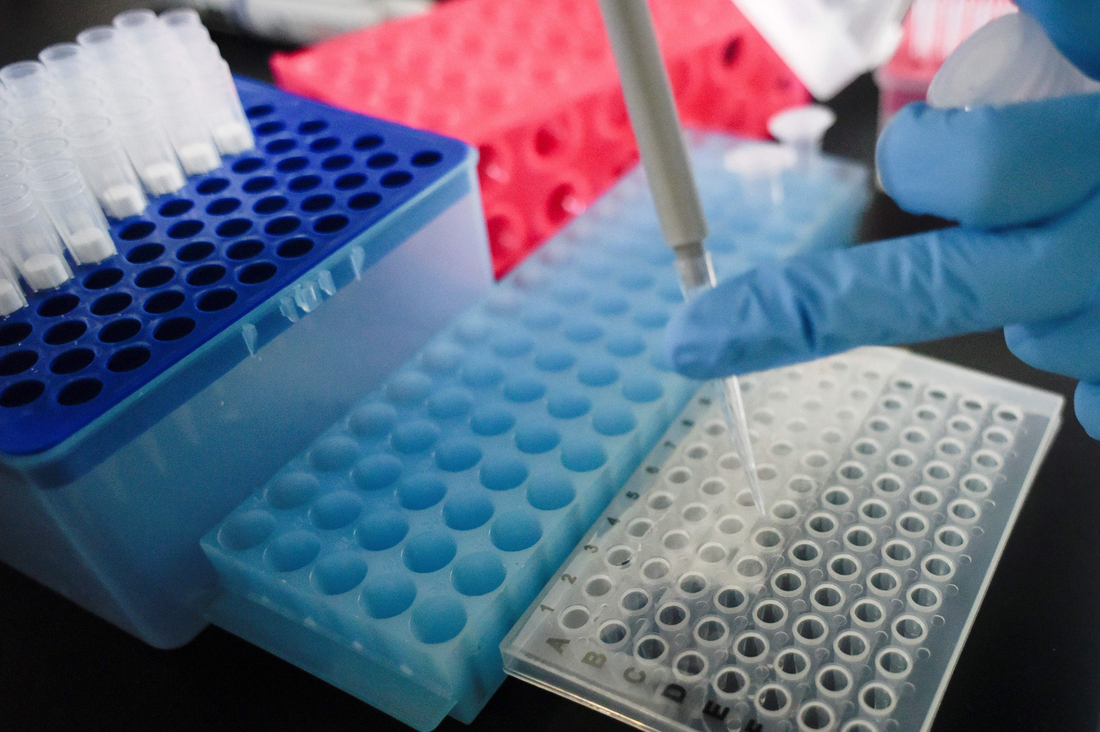

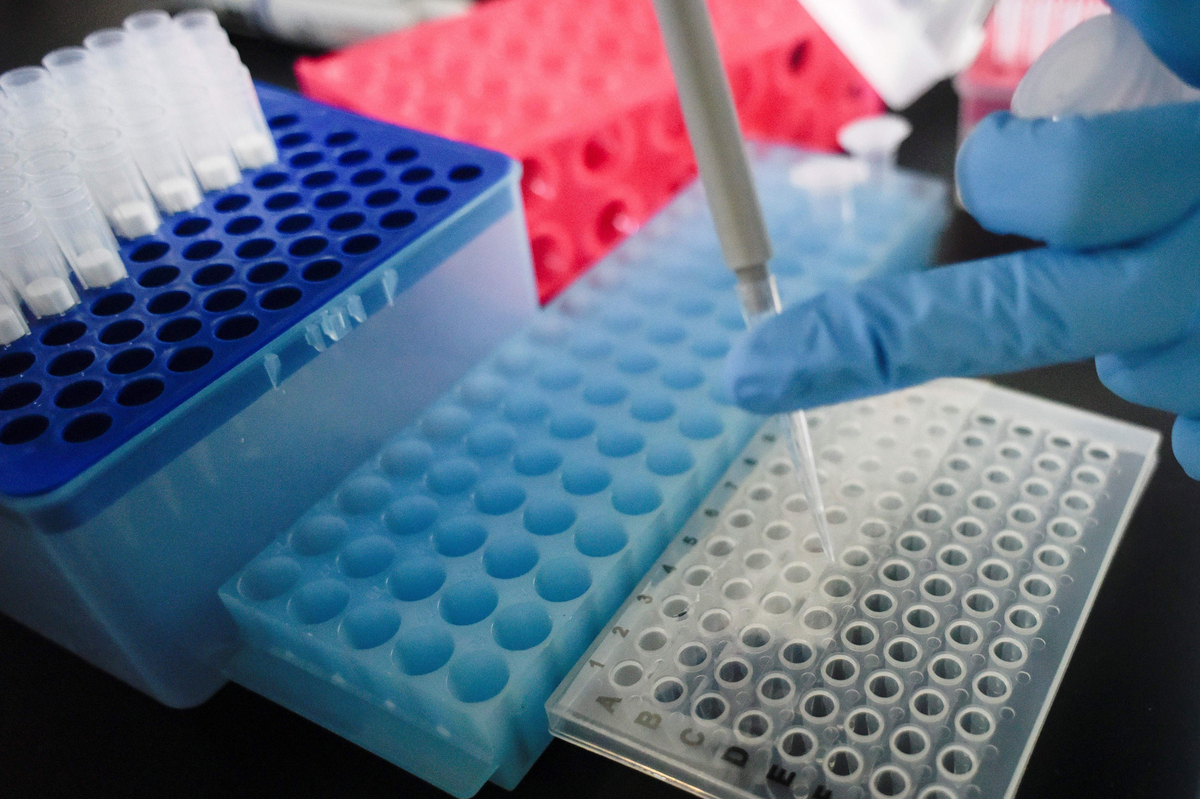

A researcher at Peking University’s Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Genomics conducting tests at their laboratory, Thursday, May 14, 2020.

Wang Zhao/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Wang Zhao/AFP via Getty Images

A researcher at Peking University’s Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Genomics conducting tests at their laboratory, Thursday, May 14, 2020.

Wang Zhao/AFP via Getty Images

The coronavirus pandemic has posed a special challenge for scientists: Figuring out how to make sense of a flood of scientific papers from labs and scientists unfamiliar to them.

More than 6,000 coronavirus-related preprints from researchers around the world have been posted since the pandemic began, without the usual peer review as a quality check. Some are poor quality, while others, including papers from China from early in the course of the epidemic, contain vital information.

The beauty of science is the facts are supposed to speak for themselves.

“In the ideal world we would simply read the paper, look at the data and not be influenced by where it came from or who it came from,” says Theo Bloom, the executive editor of the medical journal BMJ (formerly the British Medical Journal). But Bloom knows we don’t live in an ideal world. We are deluged with information, so people necessarily turn to short-cuts to help them sort through it all.

One shortcut is to look for a familiar name, or at least a trusted institution, in the list of authors.

“As human beings, I think we default to thinking ‘how do I know this, where does it come from, who’s telling me and do I believe them,'” she says.

But leaning on that has a downside. “The shortcuts we use tend to propagate what in this country we would call an ‘old boys’ network,” Bloom says. That favors biases over fresh ideas. And it’s often not a useful tool for evaluating papers about the coronavirus. Since the pandemic hit Asian and European countries first, important papers have been originating abroad from scientists often outside U.S. researchers networks.

Some of the most important research about the nature of the disease and the epidemic have come from Chinese scientists not widely known to a global audience. These papers helped identify the virus, explore how rapidly it spreads and how the disease progresses within an individual. Bloom says important insights about the unfolding pandemic came as well from researchers in Spain and Italy who were not widely known internationally.

Part of Bloom’s job at BMJ involves managing a major repository of unpublished medical papers at Medrxiv (pronounced med-archive). Some of the papers in Medrxiv end up getting published later in peer-reviewed journals, but many don’t.

Few of the submitters are familiar to Bloom, despite her many years as a top journal editor. And the sheer quantity of new information, especially from unknown labs and unknown scientists around the world, is a huge challenge.

Medrxiv, like its sister repository, Biorxiv, does only basic screening of submissions. Are they actually scientific investigations, or simply commentary? Have human experiments been performed ethically? And would a preliminary finding create public panic? (When editors fear that might be the case, they refer the study to a journal for proper peer review before posting an explosive claim).

Bloom’s job is not to judge the quality of the research. That task is left to scientists (and journalists) who read the papers.

“It takes a large investment of attention and effort to really dig deeply into a manuscript to scrutinize the methods, the claims, and the relationship between the methods and the claims,” says Jonathan Kimmelman, a professor of biomedical ethics at McGill University.

He first asks himself a basic question: Can I trust what I’m reading here?

“Knowing where a researcher is, or who a researcher is, can be part of establishing that trust,” Kimmelman says. “But I do think it harbors some dangers.”

Sometimes the freshest ideas come from young and relatively unknown scientists. And sometimes scientists with big reputations produce flops.

In the case of coronavirus research, a lot of important results come out of labs he’s never heard of, produced by people he doesn’t know. So Kimmelman tries to look for signals of quality in the papers themselves.

He recalls one paper out of China in late March that touted the benefits of hydroxychloroquine, a malaria drug that has been promoted as a possible treatment for COVID-19.

“This [finding] was pretty quickly taken up by the New York Times, and a number of different experts had fairly positive statements to say about the clinical trial,” Kimmelman recalls.

Rather than diving directly into the data and analysis, Kimmelman first looked at how the researchers had approached their work. Studies involving human beings are supposed to be registered in government databases such as clinicaltrials.gov. There, scientists declare in advance the specific hypothesis they are testing and describe how their experiment is designed.

In the case of the hydroxychloroquine study, Kimmelman discovered that the reported results had veered significantly from their previously stated experimental plan. “Those struck me as a lot of major red flags,” he says. “It probably took me something between 15 minutes and 30 minutes to come to conclusion that this paper wasn’t worth the time of day.”

Sure enough, the promise of hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 treatment eventually crumbled, as several larger studies failed to show any benefit.

Some scientists in the U.S. approach research from China with trepidation. There have been some widely publicized scandals around scientific misconduct at Chinese universities. While misconduct is hardly unique to China, scientists with only a vague sense of who is culpable may prejudge Chinese science in general. This would be a mistake, argues Heping Zhang, a professor of biostatistics at Yale University.

“There are people who cheat whenever humans are involved,” says Zhang. “It is unfair and unnecessary to be prejudiced against diligent and honest scientists regardless of how many others don’t hold up the high standard,” he writes in an email. “I have direct experience where an important and solid study may be rejected because the authors are Chinese.”

Scientists should approach each piece of research with an open mind, he says, and judge the science on its merits.

Bloom at the BMJ agrees, saying there is a danger in relying too heavily on surrogates, such as big names, or big-name journals, when evaluating a new finding.

“There are retractions and falsifications from great journals, great institutions, from Nobel laureates and so on,” Bloom says. “So, it behooves us all to try and move away from who we recognize as good.”

One way researchers are working to overcome bias is by coming together to form international research teams.

Motivated by a desire to address “a common threat to humanity,” Zhang has worked collaboratively with multiple colleagues in China to analyze trends of the coronavirus within the United States. He speculates that the Yale connection adds credibility to that research.

Lauren Ancel Meyers, a biologist at the University of Texas in Austin says she has also had the benefit of working with a postdoctoral researcher in her lab, Zhanwei Du, who hails from Hong Kong.

“Working very closely with someone from China has been incredibly invaluable to just getting basic understanding of the situation, but also to building bridges to researchers and to data that are coming out of China,” Meyers says.

Her lab, which specializes in modeling diseases, not only consumes coronavirus research, but produces it as well. One of their early papers used Chinese cellphone data to predict how the coronavirus would spread out of Wuhan, where the epidemic started, and into other regions of China. Her papers share authors around the world.

She notes that some of the important early information flowing from unfamiliar scientists in China got immediate recognition because their papers were co-authored by prominent researchers in Hong Kong and Britain.

“I imagine that some of the reaching out and some of the bridges that were built were not just to get credibility, but really to bring the brightest minds to help think through the data and what was going on,” Meyers says.

You can contact NPR Science Correspondent Richard Harris at rharris@npr.org.

[ad_2]

Source link