[ad_1]

The 2021–22 NBA season tips off on Oct. 19, and between now and then the Crossover staff will be analyzing all of the biggest story lines ahead of what promises to be an unforgettable campaign. You can find our NBA preview stories here.

Let’s start near the end, which soon may be remembered as the beginning. It’s late June on a Sunday night inside State Farm Arena, where the Hawks and Bucks are throwing haymakers in Game 3 of the Eastern Conference finals. More than 16,000 fans are on hand to witness what can fairly be labeled as the most significant NBA game ever played in the state of Georgia.

Nursing an 85–82 lead with a minute left in the third quarter and the series tied 1–all, Hawks point guard Trae Young—having already scored 15 points on an array of step-back threes, floaters and blow-bys in the period—finds himself pinned along the right sideline by two defenders. He tries to thread a pass to forward Solomon Hill but turns it over. Then disaster strikes. As he goes to run back on defense, Young steps on referee Sean Wright’s sneaker. Young’s right ankle bends. His body crumples.

“I’m like, What the f— happened? Nobody was under you,” Hawks forward John Collins recalls. “It was heartbreaking for us as a team.”

Young came back in the fourth quarter but didn’t have the explosive speed that makes him so effective. Atlanta would lose the game 113–102, then split the next two without Young. This wasn’t the only injury in the series—Giannis Antetokounmpo hyperextended his left knee two days later—but it was massive enough to make those involved wonder what could have been after the Hawks fell in six.

“To me it was our Finals,” Atlanta center Clint Capela says. “I was like, If we win this [series], we’re gonna win.”

Young thought about the moment over the summer, but he didn’t dwell on it. He speaks of the injury as if recalling what he ate for breakfast. Instead of lamenting a bad break, Young appreciates the auspiciousness of his playoff debut. “I just try and live in the moment and then if it doesn’t work out, I try to re-create that moment,” he says. “I’m really just focused on trying to make that next step, taking it even further and going to the Finals.”

Atlanta has its top nine scorers coming back. It’s the same core that, after Nate McMillan replaced Lloyd Pierce as coach on March 1, had a better record (27–11) than every team except the Nuggets and Suns. The Hawks have momentum and upside, with those top nine scorers averaging 26.8 years of age. They have defensive versatility, outside shooting and playmaking, along with length and depth at every position.

Or, as Young puts it, “We have everything.”

Yet they have to navigate the superteam era with only one clear All-Star. They suddenly face pressure to win now. They have more mouths to feed than any team in the league. They seem to have time on their side, but paying everyone his market value over the next few offseasons is impractical. “It’s gonna be hard for the franchise to keep everyone,” guard Bogdan Bogdanović says. “And everyone knows that.”

It’s increasingly difficult to build and maintain a homegrown juggernaut. The ghosts of San Antonio and Golden State—the last two dynasties that followed that template—are what these Hawks will chase. In the NBA stability is elusive. But if there’s one team that seems ripe to grab it, it’s Atlanta.

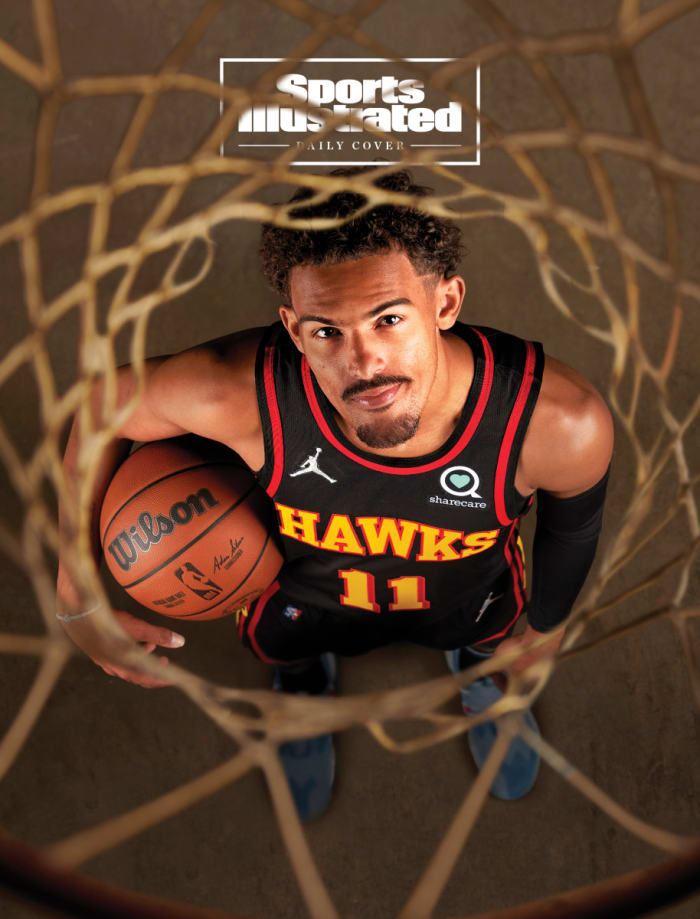

Of all the reasons to be optimistic about the Hawks’ future, the most prominent is Young, their scintillating, 23-year-old torchbearer. Atlanta has 19 nationally televised games this season, nine more than a year ago, including its first Christmas Day broadcast since 1989.

Young’s first postseason was somewhere between a mild surprise and the culmination of everything he has wanted to show off on the sport’s biggest stage. In 16 games he averaged 28.8 points and 9.5 assists against three physical, imposing defenses. He silenced a ravenous Madison Square Garden crowd, then dismantled the top-seeded Sixers. In a Game 1 win over the Bucks he finished with 48 points, 11 assists and seven rebounds. It was like watching a yellow jacket take down a crash of rhinos.

“He was amazing to me; I ain’t gonna lie,” Hawks forward De’Andre Hunter says. “So I can’t imagine what he was doing for y’all, because I see him every day.”

Orchestrating most of the offense out of a pick-and-roll (the NBA’s staple action, which he conducts more than any player), Young practically breezes into the paint. Sometimes his flight is interrupted by a hip or outstretched arm, but that’s how he draws a ton of crucial fouls. Young, at 6′ 1″ and a willowy 180 pounds, led the league with 484 made free throws last season, and people around the team aren’t concerned by the rule change—no drawing fouls using an “overt, abrupt or abnormal motion”—that was seemingly written for contact-seekers like Young.

With Young running the show, the Hawks were eighth in offensive efficiency.

Kevin D. Liles/Sports Illustrated

Young’s lobs and kickouts are devastating; his floater is the ne plus ultra of cheat-code basketball, so much so that Collins was dumbfounded by playoff opponents who didn’t trap him every time he came off a screen.

His pull-up threes don’t engender as much panic as Steph Curry’s—he’s never made more than 33.5% of them in any of his three seasons—but they still concern opponents who know Young is not afraid to take them. Statistics matter only until he drills a jumper from the logo. “You can analyze him all day long,” Hawks assistant general manager Landry Fields says. “Once he steps on the court, all that kind of goes out the window a little bit.”

The playoffs were part of Young’s ongoing learning experience, which has revolved around the friction that lies between those distant heat checks—his average three-pointers are deeper than every other player since he was drafted—and a more balanced demeanor.

“He’s got one of those fast cars,” McMillan says. “You can’t drive that car the same way on a sunny day as you can when it’s raining and snowing out there. And he was playing fast; he was taking the same shots that he was taking in the first quarter in the fourth quarter. He wasn’t adapting to conditions.”

McMillan would pull Young aside during games and ask questions—Who has the hot hand for us? Do you know a set to call for him?—designed to broaden his perspective. He knows Young has spent his entire career carrying teams since his days at Norman (Okla.) High. During his brief time in the NBA only five players have had a higher usage rate.

But to take that next step Young had to believe in everyone else even more than his brilliant passing suggests he already did. “It’s similar to Michael Jordan when he first came into the league,” McMillan says. “He started to trust his teammates. And then he started winning championships.”

To McMillan, Young’s decision-making improved down the stretch, but the tutorials didn’t end after the Hawks were eliminated. He would text Young during Finals games whenever Chris Paul pulled something off that could double as a teaching moment. Did you see that?

So far, that mentorship has translated to winning. “He knows how to control the game,” Capela says. “People like to compare him to Luka [Dončić], but at the end of their careers, all we’re gonna remember is who won the most. Like Kobe [Bryant] and [Allen] Iverson. Kobe won, so that’s the difference right there. That’s what will make [Trae] extremely special. One of the greats.”

Young’s size makes him a target on defense, but it’s an area where he says he did “a pretty good job throughout the playoffs.” He’ll also need to become more comfortable off the ball as McMillan tries to exploit him as a catch-and-shoot threat.

Above all else, as the face of the franchise, Young must assume a leadership role. One of his next steps will be fusing the fearlessness he exudes on the court into a broader magnetism off it. Early last season, Young had a conversation with Fields about what he wants to become in the NBA. The concept of leadership came up. As the season went on, Fields saw Young make strides expressing himself to teammates as Atlanta’s clear guiding light.

“Everyone has to be on board with that,” Fields says. “And if you can let [maturity and elite skill] mingle together … that’s the superstar that people want to play with.”

Teammates describe Young off the court as reserved and soft-spoken, tending to spend most of his time around family. But who he is during games has started to consume the organization’s culture. The NBA is brimming with self-belief. The unshakable way Young puts his on display makes it uniquely transmittable—and beloved by everyone battling on the same side.

“I’m not gonna say I’m not as confident as he is; I’m just saying you can see his,” small forward Cam Reddish says. “He’s coming down three times in a row. ‘I’m gonna let this jawn go because I’m feeling it,’ like, that’s confidence. And I think that rubs off on everybody. Oh, he feeling it? We all feeling it.”

By extension, the Hawks have replaced hesitancy with swagger. “I just think everybody plays with excitement,” Young says. “That’s all I try to do. You see guys with smiles on their faces when they make big plays, and guys on the bench happy for one another. That’s all it’s about. I think that’s hopefully what my teammates all like about playing with me.”

Collins compares their style to a twist on the Showtime Lakers: “You’ve got lobs everywhere. Threes flying everywhere. Dudes shimmying. Dudes dunking on people. We bring that Atlanta juice to the court.”

Key veterans such as guard Lou Williams, forward Danilo Gallinari and even the 27-year-old Capela provide an important perspective from all their time in the league. But with so many young players, some of the Hawks’ most important contributors are too young to know what they don’t know. “It’s like a college team mixed in with a couple foreign guys,” guard Kevin Huerter says with a laugh. “Everyone’s joking around on the planes…. It’s more of a casual hangout than it is guys on their phones or in their headphones.”

For now, that communal energy is a force field protecting the team from the corrosiveness of self-interest and fame. Power forward Onyeka Okongwu is 20. Reddish is 22. Young, Hunter and Huerter are 23. Collins just turned 24. Their willingness to cede minutes, touches and shots for the good of all will go a long way toward deciding how successful they can be over the next few seasons.

“It’s three things in the league that I look at: I want to play, I want to make money and I want to win,” incoming Hawks assistant coach Nick Van Exel says. “And it’s pretty much that order with a lot of players.”

During the offseason, Young received his max, five-year, $207 million contract extension, while Collins was rewarded with a five-year, $125 million deal despite seeing his individual numbers dip during the playoffs. “I’m just not a guy that just, in the best way possible, cares too much about what the f— is going on as long as we’re winning,” Collins says. “I feel like you need guys like me who are willing to do that…. That’s what needs to happen for us to make all this s— work.”

Capela just signed a two-year, $46 million extension, as well. Huerter, who had foot surgery after the season, is extension-eligible without an agreement at press time. Reddish and Hunter will be up for their own raises next summer.

Last season Kevin Durant said the Hawks had seven or eight starters on their roster. He wasn’t wrong. On the eve of a campaign that will bring far more attention to Atlanta than any before it, sacrifice is being embraced out loud. “I know I’m nice,” Reddish says. “So when my opportunity comes—and it came in the playoffs a little bit, y’all saw a little sneak peek—then when it’s time to play my role, I’ll play my role. When you start getting good at your role, then your role gets bigger. It’s a process. Sometimes it’s gonna be hell. But you work through that.”

Reddish’s best friend on the team and fellow Philadelphia native, Hunter, uses the recent Warriors as a guide; the way Klay Thompson and Draymond Green accepted fewer shots to make room for Durant was critical. But when high expectations and the pursuit of higher salaries are thrown into the mix, NBA history tells us a happy ending is anything but guaranteed.

McMillan will work to put everyone in a role that’s best for the team, but “there’s only so much I can do,” he says. “Everybody’s gonna have to sacrifice. Everybody. Will they accept that? I don’t know. Kevin Huerter had a hell of a year last year, but why did he have a hell of a year? Because he had minutes. He got minutes because Cam was out. Dre was out for over half the season. [Bogdanović] was out for a number of games. Now you got all these guys coming back. [Huerter] ain’t getting those minutes. And they’re not gonna get those minutes.”

That central tension may be amplified by another: The Hawks will in all likelihood need (at least) one more marquee name to win a championship. That player may already be under contract, whether it’s Collins—who adamantly believes he’s about to make his first All-Star Game—Hunter or someone else, but for now it’s a critical unknown.

A consolidation trade could be in Atlanta’s best interest, particularly for a star who’s intrigued by the team’s success—a possibility the front office mentioned during the offseason. “I know there’s rumors out there, but our focus right now is only what’s in our airspace, while also being open to when that opportunity [for a trade] comes,” Fields says. “We’re going to entertain a lot of different paths to success.”

McMillan can’t worry about that, though. He starts listing players he has coached who rose to a level that was never certain or even expected: Rashard Lewis, Brandon Roy, LaMarcus Aldridge and Victor Oladipo. “When [the Pacers] traded for [Oladipo] I didn’t set out to make him an All-Star,” McMillan says. “It was like, I’m gonna try to take advantage of your skill . . . which is the same thing we’re doing here with these players.”

Without a second star, their chances of advancing beyond where last year ended, or even getting there again, are slim. “One is not gonna do it,” McMillan says. “And Trae is one of those guys…. Now what we gotta do is we gotta continue to develop him. And we gotta develop two more.”

The Hawks were 11th in the East when McMillan took over and wound up with the No. 5 seed.

Jesse D. Garrabrant/NBAE/Getty Images

It’s September at the Hawks’ practice facility. Tucked inside a quiet suburban campus about 20 minutes north of downtown, a majority of the team is already in the gym.

In the back corner of the gym rests the team’s “competition shooting board” with records for eight different drills from last year. (Bogdanović is the clubhouse leader for seven of them, all achieved as he looked for a way to motivate himself while out with a right knee injury last season.) A giant whiteboard that has yet to be written on hangs to its side. Above midcourt McMillan, about to begin his first full season as Atlanta’s coach, surveys the whole floor from his office.

Wearing a white Hawks practice T-shirt and red warmup shorts, the 57-year-old is trying to balance rosy hopes with the need to be head-down humble. “I really do approach it one day at a time,” says McMillan, who signed a four-year contract in July. “I know what expectations are for us this year. But I can’t prepare this team right now for May and June. We ain’t there yet.” McMillan shifts in his chair, brings his hands together and prepares to open up.

In early August he went back home to visit family in Raleigh. He had breakfast with his younger brother, Lorenzo, and they were finally able to celebrate Atlanta’s playoff run and daydream about the upcoming season. Three weeks later, Lorenzo died. “I think death should teach us something, and what it taught me … man, we gotta live every day to the fullest, because we’re not promised tomorrow,” McMillan says. “So to sit here and talk about what we’re going to do in May, who knows if I’ll even be here in May, you know? It’s taking care of today.”

It’s an outlook he’ll impress upon his team as often as he can. This season won’t be like the last, when an early road win over the Nets prompted a huge celebration. Experienced voices around the team understand that.

“You come from being bottom of the barrel to the hunted. It’s a whole different ball game,” Van Exel says. “So you got 82 games where pretty much you’re like the Lakers. You’re like Brooklyn. There’s no nights off for you.”

Few teams have a brighter outlook than the Hawks. With myriad options for team-building, the straightest path may be the most rewarding. If they can collectively ascend around Young, develop each season and self-deny for the sake of winning, last year’s run will be seen as the start of something unrivaled in the Hawks’ 54-year history in Atlanta. With all due respect to Mike Budenholzer’s 60-win team of 2014–15; Mike Woodson’s steady playoff march during the aughts; Steve Smith, Mookie Blaylock and Dikembe Mutombo; the spectacular show Dominique Wilkins put on in the late 1980s; Hubie Brown; or Lou Hudson’s playoff battles against Jerry West’s Lakers; this could be new ground since the organization moved in ’68 from St. Louis (where they won a championship in ’58).

“It’s rare in the league for a young core to grow, and most of the time I feel like it works out when you truly let a young core grow together,” Collins says. “I feel like this is the final stage of us blossoming into being a real championship team.”

As Game 6 of the conference finals came to a close with the Hawks down double digits, Young started to untuck his jersey in front of Atlanta’s bench. With a blank stare aimed at the court, he nodded as teammates slapped his back and spoke words of encouragement. Just before the final horn, he bent over and placed both hands on his knees. Milwaukee center Brook Lopez walked over to offer a hug before Young sauntered back to the locker room. Moments later, as he approached the tunnel one last time, Young shouted three words at State Farm Arena’s lingering crowd:

“We’ll be back!”

To Atlanta’s franchise pillar, the statement is a byproduct of his own conviction. Which means everybody who stands behind him has no choice but to believe the exact same thing.

More NBA Coverage:

• Luka Dončić Is Learning From the Best

• Karl-Anthony Towns Opens Up About His Season of Grief

• The Lakers’ Biggest Concern Is Age, Not Fit

• How I Got Cut From the G-League

[ad_2]

Source link