[ad_1]

Environmental groups focused on climate change want to eliminate natural gas use in buildings, and that includes cooking with gas stoves.

Erano Bundoc/Getty Images/EyeEm

hide caption

toggle caption

Erano Bundoc/Getty Images/EyeEm

Environmental groups focused on climate change want to eliminate natural gas use in buildings, and that includes cooking with gas stoves.

Erano Bundoc/Getty Images/EyeEm

Americans love their gas stoves. It’s a romance fueled by a decades-old “cooking with gas” campaign from utilities that includes vintage advertisements, a cringeworthy 1980s rap video and, more recently, social media personalities. The details have changed over time, but the message is the same: Using a gas stove makes you a better cook.

But the beloved gas stove has become a focal point in a fight over whether gas should even exist in the 35% of U.S. homes that cook with it.

Environmental groups are focused on potential health effects. Burning gas emits pollutants that can cause or worsen respiratory illnesses. Residential appliances like gas-powered furnaces and water heaters vent pollution outside, but the stove “is the one gas appliance in your home that is most likely unvented,” says Brady Seals with RMI, formerly Rocky Mountain Institute.

The focus on possible health risks from stoves is part of the broader campaign by environmentalists to kick gas out of buildings to fight climate change. Commercial and residential buildings account for about 13% of heat-trapping emissions, mainly from the use of gas appliances.

Those groups won a significant victory recently when California developed new standards that, once finalized, will require more ventilation for gas stoves than for electric ones starting in 2023. The Biden administration’s climate plan also calls for government incentives that would encourage people to switch from residential gas to all-electric.

The gas utility sector sees the focus on possible health effects of stoves as a growing threat to its survival, and it’s critical of groups raising the issue. In commenting on the new California standards, Ted Williams of the American Gas Association (AGA) called these groups “organizations who are first and foremost interested in electrification for climate concerns.” He said they “have glommed onto indoor air quality as being a soft spot in the issue of direct use of natural gas.”

The gas utility industry is fighting to preserve its business by downplaying existing science on gas stoves and indoor air quality. It points out that federal regulators have declined to regulate gas stoves more stringently. And it is investing in a range of campaigns to remind customers that cooking with gas is cheaper.

This battle is aimed at influencing your decision the next time you buy a new cookstove.

Environmental epidemiologist Josiah Kephart studies pollution from cooking. He says it’s his family’s highest priority to get rid of their gas stove and replace it with a less-polluting electric one.

Jeff Brady/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jeff Brady/NPR

Environmental epidemiologist Josiah Kephart studies pollution from cooking. He says it’s his family’s highest priority to get rid of their gas stove and replace it with a less-polluting electric one.

Jeff Brady/NPR

An epidemiologist reconsiders his gas stove

Josiah Kephart is an environmental epidemiologist at Drexel University in Philadelphia who researches indoor air pollution from cookstoves in Latin America. On a sunny summer morning we met in his kitchen to test the pollution from his family’s gas stove.

If you have an electric stove, the energy for cooking may come from fossil fuels, but the combustion happens at a power plant far away, Kephart says. “When you have a gas stove, that combustion is actually occurring right in your kitchen — you can see the blue flame down there,” he says. “There is no smoke-free combustion.”

The most common pollutants from gas stoves are nitrogen dioxide (NO2), carbon monoxide and formaldehyde. Advocates now are mostly focused on NO2, which the Environmental Protection Agency says is a toxic gas that even in low concentrations can trigger breathing problems for people with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

To learn how much NO2 Kephart’s gas stove releases, NPR rented an air monitor.

Kephart has two young children, and research, including this 1992 study, shows that kids who live in a home with a gas stove have about a 20% increased risk of developing respiratory illness.

A nitrogen dioxide air monitor in Josiah Kephart’s kitchen shows 0.159 parts per million, or 159 parts per billion. That’s above the World Health Organization hourly guideline of 106 ppb.

Jeff Brady/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jeff Brady/NPR

A nitrogen dioxide air monitor in Josiah Kephart’s kitchen shows 0.159 parts per million, or 159 parts per billion. That’s above the World Health Organization hourly guideline of 106 ppb.

Jeff Brady/NPR

At first, the air monitor shows background levels in Kephart’s kitchen are about 24 parts per billion (ppb). That’s expected for a home with a gas stove, but still higher than the World Health Organization (WHO) annual average guideline of 5 ppb. The EPA does not have standards for indoor NO2 levels.

Kephart starts by boiling a pot of water and baking blueberry muffins. “So this is supposed to be a very normal scenario of cooking a meal in the kitchen: We have the oven on 375 and one stove burner on,” he says.

After 12 minutes, the monitor starts to spike, showing NO2 levels of 168 ppb. “So now we have exceeded the [WHO] hourly guideline of 106 ppb by about 50%,” says Kephart. “If you have kids or any sort of lung condition, this is at a level where, in the literature — in the science — we have seen people start to have these changes in their lungs that could give them worse symptoms or could worsen their disease.”

After half an hour, the air monitor shows 207 ppb — nearly twice the WHO guideline.

There is no hood over Kephart’s stove to vent the pollution outside. Instead, like many Philadelphia row houses, there’s an old room fan high up in a wall. It vents outside, but even after Kephart turns it on, NO2 levels remain high. Kephart says that’s because the fan is about 6 feet away.

We head upstairs to check NO2 levels in his children’s bedroom. At first, levels are low because the bedroom door is closed and a window is open to let in fresh air. With the door open, just a few minutes later the levels rise to 109 ppb, exceeding the WHO guideline.

Kephart’s family moved into this row house about a year ago, and his wife likes cooking on a gas stove. But, he says, “It’s our highest family priority to get it out and to get an electric stove.”

He says it’s not a given that having a gas stove in your home will make you sick or lead to asthma. It’s a risk calculation. “If you have a large kitchen with really up-to-date ventilation systems,” he says, “and you have a healthy body, this may not be your biggest concern or the biggest risk to your health.”

But when it comes to his children, Kephart is extra cautious. “It doesn’t make any sense to me to add to the risk of them developing asthma or other respiratory diseases by having this source of pollution right inside our house,” he says.

No federal agency regulates gas stove emissions

Federal agencies, including the EPA and the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), say they are paying attention to the gas stove pollution issue. But none has moved to regulate potentially harmful emissions, a point the gas industry emphasizes to dismiss concerns about possible health effects of stoves.

“Someone’s going to have to claim this issue and really make a change, because I think as more consumers learn about it, you feel upset,” says Seals with RMI.

RMI and three other environmental groups issued a report last year labeling gas stove emissions a threat to human health. They called on policymakers to regulate them more strictly and provide incentives for Americans to switch to electric.

Research into the possible health effects of residential stoves isn’t news to the gas industry.

For decades, gas utilities themselves and their powerful trade group, the AGA, have conducted their own research on stove pollutants, including nitrogen dioxide. That work even led to new ways of reducing NO2 pollution, such as this patent for inserting a metal rod into the flame to lower the temperature and reduce NO2 emissions. In 1990, a big step was getting rid of pilot lights that burn 24 hours a day. Still, it’s not possible to entirely eliminate emissions when burning an unvented fossil fuel in your home.

Now, the gas utility industry sees this growing research on health effects of stoves as an existential threat. The AGA responded to the RMI study by pushing back. It released public fact sheets to counter the report and rebuttals to individual articles in The Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic and on The Weather Channel.

Internally, the AGA developed a response plan that lays out a timeline for rebutting the RMI report. The timeline was obtained by the environmental watchdog group Climate Investigations Center through a public records request and shared with NPR.

The AGA planned a new research project comparing emissions from electric stoves to gas ones. Vice President for Communications Jennifer O’Shea offered no details about the results so far. “We continue to focus on this important issue to ensure that consumers understand the benefits and safety around cooking with gas,” she said in an email. “We will keep you posted as we have new data to share.”

The AGA responds to indoor air quality concerns for gas stoves by pointing out that cooking fumes come from all types of stoves. While those can be a significant source of air pollution, scientists specifically identified homes with a gas stove as a risk for children in the 1992 study. The AGA dismisses the research as a literature review of other studies. But the World Health Organization cites the study and others in developing its most-recent indoor air pollution guidelines.

Your stove just needs to vent

To reduce NO2 emissions in your home, the EPA suggests using an exhaust fan above your gas stove that’s vented to the outdoors. The AGA says that while all gas-fired residential cooking ranges are designed to operate without outdoor ventilation, installing one can improve indoor air quality.

In the absence of federal oversight, California is taking action. The California Energy Commission (CEC) has approved standards that would require extra ventilation for gas stoves over electric ones. Smaller living spaces would require even stronger hoods for gas stoves because pollutants reach unhealthy levels faster.

If the rules take effect as planned in 2023, the CEC staff believes they would be the first requirement of this kind in the nation. The rules also would be a significant win for the environmental groups trying to raise concern about the effects of gas stoves on indoor air quality.

In comments to the CEC, the AGA was critical of the proposed standards, saying such decisions should be made at the federal level and through voluntary standards organizations. But federal agencies are moving slowly on this issue, and scientists say the world needs to take dramatic steps now to avoid the worst effects of climate change, including reining in gas use.

The climate connection to your stove

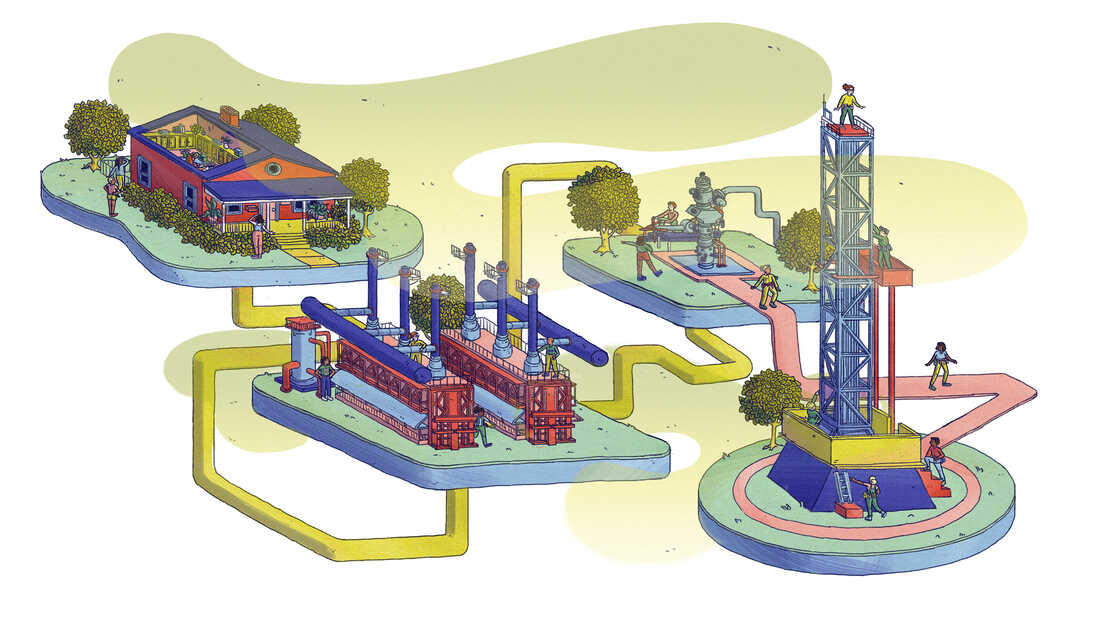

The gas line out the back of your stove is connected to a production and supply chain that leaks methane from start to finish.

Gas stoves emit pollution into your house and they are connected to a production and supply system that leaks the powerful greenhouse gas methane during drilling, fracking, processing and transport.

Meredith Lynne for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Meredith Lynne for NPR

Gas stoves emit pollution into your house and they are connected to a production and supply system that leaks the powerful greenhouse gas methane during drilling, fracking, processing and transport.

Meredith Lynne for NPR

“Methane, which is what natural gas is made of, just really wants to leak,” says Seals with RMI. That’s a problem because methane is a much more potent greenhouse gas than even carbon dioxide, though it doesn’t linger in the atmosphere nearly as long.

President Biden’s climate plan includes a goal to cut the carbon footprint of buildings in half by 2035 through incentives to retrofit homes and businesses with electric appliances and furnaces.

The AGA says methane emissions from gas utilities account for 2.7% of all greenhouse gas emissions, and they’ve declined nearly 70% since 1990, even as utilities have added customers. But the rest of the supply chain also leaks methane, including drilling, fracking, processing and transport. Some equipment is designed to vent, but much of the gas that escapes is unintentional and has been linked to tree deaths in places such as Boston and Philadelphia.

In recent years, natural gas has been credited with reducing carbon dioxide emissions as cleaner-burning gas power plants replaced coal ones. The overall gas industry, including big oil companies with natural gas holdings, has worked to reduce emissions and supported efforts to more strictly regulate methane emissions. But to avoid the worst consequences of climate change, scientists say most of the world’s fossil fuels, including nearly half of the gas reserves, will have to stay in the ground.

Biden’s plan also sets a goal of net-zero emissions across the economy by 2050. A growing list of studies, such as ones from Princeton University, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the National Academy of Sciences, find that meeting that goal will require electrifying buildings, making appliances more efficient, and powering them mostly with emission-free sources like renewable energy.

AGA President and CEO Karen Harbert often says her industry wants to be part of solving the climate problem and has developed a position statement on the issue. “If the goal is to reduce emissions, we’re all in,” she told NPR earlier this year. “If the goal is to put us out of business, not so much.”

Harbert’s industry also says it’s developing cleaner alternatives, including so-called renewable natural gas from landfills and manure, that can be mixed with hydrogen and run through the existing utility pipeline network.

The gas stove is a “gateway appliance”

To encourage more people to ditch natural gas, environmentalists are focusing on the gas stove. At first it may seem like an odd choice because other gas-burning devices in the home consume more fuel, notably furnaces.

But the stove is seen as a “gateway appliance” that drives the building of a vast fossil fuel infrastructure from wellhead to home. Talk to builders and real estate agents and many will say buyers want a gas stove. And gas utilities have helped fuel that assumption.

“We have to start talking about electrifying our buildings, and it’s just really not that sexy to talk about your water heater, but you probably can talk to your friends about their stove,” says RMI’s Seals. And once the switch to an electric stove happens, the thinking is that people will be more likely to switch water heaters, dryers and furnaces too.

It’s not just environmental groups signing on to widespread electrification. The New England Journal of Medicine recently published an opinion piece by three physicians who recommended that “new gas appliances be removed from the market,” along with ending industry subsidies and banning new gas hookups in buildings.

The Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank, wants the federal government to offer incentives to switch from gas to electric appliances, water heaters and furnaces. The group says that to meet the goal of limiting global warming to under 3 degrees Fahrenheit, switching to electric appliances has to happen now, because if new gas appliances replace old ones, they can last, and keep polluting, for decades. Earth has already warmed about 2 degrees Fahrenheit since the mid-1800s.

Jane Stackhouse points to the electric heat pump (left) that replaced a gas furnace and to a more efficient electric water heater (right). Her utility bills are about the same, but now she also has air conditioning for extra warm days made worse by climate change.

Jane Stackhouse

hide caption

toggle caption

Jane Stackhouse

Jane Stackhouse points to the electric heat pump (left) that replaced a gas furnace and to a more efficient electric water heater (right). Her utility bills are about the same, but now she also has air conditioning for extra warm days made worse by climate change.

Jane Stackhouse

She got rid of gas for her grandchildren

Jane Stackhouse of Portland, Ore., is among a small group of people who already have chosen to disconnect from their local gas utility. She did this last year after Republican state lawmakers successfully blocked a climate-focused “cap and trade” bill.

In response, Stackhouse says she decided that “I had control over this duplex that I own, and so I started looking for a contractor who would make me all electric.”

She replaced the gas stove, furnace and fireplace in each unit, then installed more efficient electric water heaters. For both sides of the duplex it cost her more than $35,000. She says her utility bills remained about the same even though she added air conditioning to deal with increasingly hot summers in Portland.

Stackhouse says it makes her verklempt to think about how climate change will affect her grandchildren’s lives: “It was my wee contribution to helping clean things up.”

[ad_2]

Source link