[ad_1]

In the mid-1980s, Lee Soo-man, a folk singer studying computer engineering in California, decided to return to his native South Korea. Inspired by what he had seen on MTV — the 24-hour-a-day television network playing music videos — he formed SM Entertainment and set about replicating the success of the highly-trained all-singing, all-dancing groups like The Jackson 5 and, later, New Kids on the Block.

Three decades later and the near-$4bn initial public offering of Seoul music agency Big Hit Entertainment expected in October marks a new high point in the history of Korea’s brand of popular music spearheaded by Mr Lee — K-pop.

BTS — a seven-member boy band formed 10 years ago by Big Hit founder Bang Si-hyuk — has propelled K-pop to the top of US music charts. The group’s global reach, coupled with the triumph of dark comedy Parasite at this year’s Oscars, has, in the eyes of many South Koreans, demonstrated the global appeal of the country’s cultural offerings.

“It is truly amazing. It is a splendid feat that further raises pride in K-pop,” said Moon Jae-in, South Korea’s president, on September 1 after “Dynamite”, by BTS, became the first Korean song to top the Billboard Hot 100.

Underpinned by the star power of the world’s hottest boy band, the Big Hit IPO is Korea’s biggest share listing in three years. But it is the metrics revealed by the deal, in particular the value and growth potential that bankers see in BTS, which have stunned investors, and is shifting the discussion around K-pop from a cultural curiosity to a serious investment proposition.

The pricing implies that shares will start trading at 76 times Big Hit’s projected earnings for 2020; the valuation indicator is five times that of Samsung Electronics, Korea’s most important company and the world’s biggest producer of smartphones and computer chips. The prospective market capitalisation of $3.9bn also makes Big Hit more valuable than the country’s three largest listed music agencies combined.

Lee Jin-man, an analyst at Seoul brokerage SK Securities, says that alongside companies developing electric car battery technology and new pharmaceutical treatments, entertainment groups like Big Hit are fast becoming “the new drivers” of South Korea’s stock market.

Yet the unprecedented international fervour for Korean culture comes at a time of upheaval in Korean society. A new generation of women are putting the spotlight on the nation’s dark underbelly: a patriarchal society plagued by misogyny that critics say is endemic to the high-pressure Korean entertainment industry.

Whereas the booming entertainment industry has so far been mostly successful in developing its wholesome, often cutesy, image, this is in stark contrast to the reality for many Korean women. Over the past two years this unpalatable side of Korean society has dominated headlines via a string of high-profile #MeToo cases, involving both K-pop stars and senior politicians, as well as a spate of sexual violence against young women and girls.

The dichotomy raises questions for not just hundreds of entertainment companies and hordes of foreign investors, but also the tens of millions of fans all focusing their attention on Korea: will the country’s moment in the sun be overshadowed, or even derailed, by the abusive practices towards women across Korean society?

“K-pop has so far built a positive image internationally but this image conflicts with the reality of the industry and Korean society,” says a US hedge fund manager with investments in the country, who asked not to be named. “Behind the scenes, sexual assault is not uncommon . . . there is concern over the wrongdoing that continues in the industry.”

A new ‘cultural superpower’

As the final curtain drew on the BTS world tour last October, singer Kim Nam-joon — known as RM — sobbed on stage at Seoul’s Olympic stadium as he told BTS fans — a group dubbed Army — that he “loved” them. Fans’ reciprocal devotion lies at the heart of the success of Korea’s cultural explosion. Their commitment to their “idols” is more akin to football fanatics than the typical following of a leading film star or pop group. When BTS released “Dynamite” on YouTube in August, it was viewed more than 100m times within 24 hours, a new record for the website.

Experts diverge when attempting to explain the popularity. Some point to organic growth based on a visceral connection between the artists and their audience. “BTS’s authenticity permeates every part of their music and life, providing an extreme sense of unity and comradeship to their fans,” writes author and critic Kim Young-dae in his book analysing the group’s first 16 albums. “This is a revolutionary shift in pop music that normally regards fans as external entities.”

Others see a formulaic, even nefarious, system at play with the entertainment groups pumping out an endless stream of vapid content, all carefully manufactured to keep impressionable fans, in particular teenage girls, hooked. Hyun-joo Mo, a Seoul-based researcher in Korean youth culture with the University of North Carolina, argues that being part of the communities that form around a particular group or star has become a toxic addiction for millions of young people trying to escape voids and challenges, including gender inequalities, in their own lives.

“They want to find an alternative reality,” she says. “For them, that is fandom . . . it is a desperate dependence.”

Yet the business model pioneered by SM’s Mr Lee has proved successful. “He merged trendy dance music from the US and the idol training system that Japan had been developing for a decade to create a hybrid genre called K-pop idols,” Mr Kim writes. Scores of agencies built the K-pop industry centred around this trainee system.

Today, in hundreds of basement studios across Seoul, children and teenagers train for up to six hours after school, sharpening their dance and singing skills. The gruelling regime typically lasts four or five years before the lucky few fledgling stars are selected into groups and marketed to the public. The Korea Entertainment Producers Association counts more than 370 music agencies as members. Between them they boast about 3,000 K-pop artists. “They are not targeting any specific country or region; they are trying to go global,” says Kim Myung-soo, KEPA director.

Still, before the arrival of BTS and Parasite on to stages and screens most mainstream western audiences had only fleeting exposure to hallyu, the “Korean wave” of cultural exports. In 2012, Psy’s “Gangnam Style”, a madcap electronic music parody about a flashy area of Seoul, became an unlikely global hit. Cinema aficionados might have encountered Korean films such as Chihwaseon or Oldboy, which won critical acclaim in the early 2000s.

Closer to home, though, Korean music, film and television dramas have been steadily building popularity across Japan, China, Hong Kong and Taiwan, as well as south-east Asia. The value of the “cultural exports” grew roughly fourfold to $10.4bn in 2019, from $2.6bn 10 years earlier. The figure equates to one month’s worth of computer chips exports, Korea’s most important product. Sales of Korean-made consumer goods like cosmetics and confectionery, as well as Samsung’s smartphones and Hyundai’s cars, benefit from the marketing power offered by groups like BTS and Blackpink — the most popular girl band with more YouTube subscribers than UK singer-songwriter Ed Sheeran.

For a country with few natural resources, hallyu’s economic contribution is significant. Sung Mi-kyung, a researcher at the culture ministry, says Korea’s new status as a “cultural superpower” has boosted its brand value overseas immensely. “It is hard to ignore the power of cultural popularity on the global stage,” she says.

‘Shiny outside, rotten inside’

South Korea, which is pushing for entry into an expanded G7 of leading nations, ranks 108 out of 153 countries in the World Economic Forum’s latest global gender gap report. In a country obsessed with global comparisons and foreigners’ perceptions, poor gender equality has for years been an embarrassment. But now there are signs that the combination of intense scrutiny inherent in K-pop fan obsession and the country’s deeply held sexism threatens both the entertainers and their management companies — whose profits are often pegged to a single popular act.

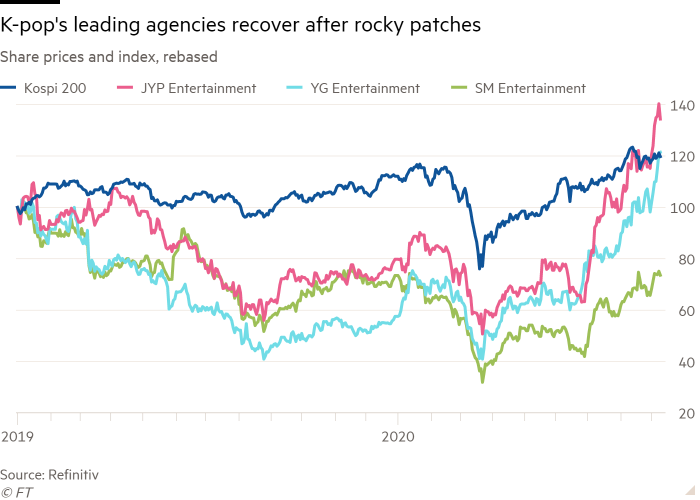

A spate of crimes and allegations connected to entertainment groups last year sparked a backlash against the industry among many women. At the height of the public outrage, share prices across the three biggest listed groups shed more than one-third of their value. But the cases also tore down the veneer of wholesomeness. Two celebrities, one with links to YG Entertainment, were jailed for rape. Two K-pop stars in their twenties took their own lives after vicious online attacks, intensifying the criticism.

“The scandals sparked a lot of external criticism that the industry is shiny on the outside but rotten inside; the industry is now trying to clean up,” says Ms Sung, the researcher.

Despite their growing global footprint the major entertainment groups — including JYP, SM, YG, Big Hit and CJ Entertainment, the film production and distribution giant behind Parasite — all declined to be interviewed for this story.

But a nod to the risk is found in Big Hit’s Korean-language regulatory disclosures filed for the IPO: “There are no artists in our company and subsidiaries who are involved in serious events that could hurt our image, for example, drug use, gambling, sex crimes, tax evasion, and discord with [band] members. Nevertheless we cannot completely rule out the possibility that individual artists’ deviation in the future could hurt our reputation.”

Ms Mo, the expert in Korean youth culture, adds that while Korean stars “may not all be fake — some of them may be very good, new men”, many appear to be “like Jekyll and Hyde” in their public and private personas.

Some investors contend that depictions of the Korean entertainment sector as seedy and sexist are exaggerated. They also play down the likelihood of industry-wide fallout stemming from problems linked to misogyny, suggesting also that the exposure of #MeToo cases in Korea reflects progress in women’s rights.

When Goldman Sachs initiated coverage of JYP last year, the bank’s analysts noted the would-be stars’ years of training included a systematic approach to “mitigate any potential ‘human risk’” via “personality coaching” and regular psychiatric consultations. “The company has always placed an emphasis on ‘moral and ethics’ above all else, and the founder JY Park has taught all his artists that the most important characteristics to becoming a star are ‘honesty, integrity and humbleness’,” the bank’s analysts noted.

Chan Lee, managing partner at Petra Capital Management, a Seoul fund with K-pop investments, gave a more candid view: though certainly “not condoning” the behaviour, such scandals were “part of entertainment”. “While it could have short-term effects on certain bands, certain people, overall it is not going to be that meaningful,” Mr Lee says. “Look at the US, Harvey Weinstein — Hollywood still goes on.”

Cultural reckoning ahead?

In mid-2019 two female Korean university students aiming to enter an investigative journalism competition started exploring dark corners of the country’s internet. The pair discovered that online chat rooms, run on the popular Telegram Messenger app and known as “Nth Rooms”, were being used to distribute and view child sexual abuse material in what is now believed to be the worst case of sexual exploitation in the nation’s modern history.

The students, who requested anonymity for safety reasons, alerted the police. Investigations continue but by March this year authorities confirmed that more than 70 victims, one quarter of whom were minors, had been coerced into performing sex acts, some violent. Many were blackmailed into silence. The audience was estimated at more than a quarter of a million. “I couldn’t get the images out of my head . . . they were in my dreams,” one of the pair tells the FT. “I felt a huge sense of helplessness.”

While there is no suggestion the Nth Room crimes had any connection to the entertainment industry, their uncovering showed that just as companies and the government seek to draw attention to South Korea by leveraging hallyu, a new generation is working equally hard to expose what they see as a crisis facing many women.

Ryu Ho-jeong, the country’s youngest parliamentarian at 28, and one of 57 women in the 300-seat National Assembly, says an antiquated legal framework for sexual violence must be overhauled. “The law still stipulates that rape must involve assaults and threats — therefore rape is classified as such only when the victims strongly resisted. Many victims have not been protected properly.”

In July, Park Won-soon, the popular mayor of Seoul and a leading presidential contender, was found dead shortly after allegations of sexual harassment covering a period of several years were reported. The revelations raised questions over the ability of men in powerful positions to cover up wrongdoing, but also suggested that more victims are willing to speak out.

In another sign of change, young women are increasingly taking to social media in response to the frequent threat of molka — men secretly filming women without their knowledge, often in public toilets, changing rooms or other private situations, and publishing the material online.

Amid this cultural reckoning there is no guarantee the entertainment industry will put its own house in order — despite companies’ assurances.

Leighanne Yuh, an expert in Korean culture and history at Korea University, says while the abuse exposed by cases like the Nth Rooms and the K-pop scandals is complex — pointing to political and legal issues — the problems have deep roots in the neo-Confucian belief propagated that women are simply subordinate to men and not to be respected. “This cuts across all generations and all social classes because this is so fully ingrained in Korean culture,” she says.

Lee Eun-eui — a lawyer and women’s rights advocate who a decade ago successfully won a lawsuit against Samsung over its failures in handling her complaints of sexual assault — says the string of high-profile cases has sparked knee-jerk promises by officials and lawmakers but has not led to the sweeping changes that South Korean society needs.

“We pay the price for what we have been neglecting,” she says.

[ad_2]

Source link