[ad_1]

How it can be that two Intel 11th-gen Tiger Lake notebook PCs, with exactly the same chip inside, can offer performance that differs by up to 37 percent? And more importantly, how can you tell the difference?

The short answer is: You can’t. An unfortunate side effect of how Intel develops processors like Tiger Lake will make it more difficult for consumers to determine the actual performance of a laptop just by reading a list of its features, and it will probably get harder over time.

The problem is that Intel is designing mobile microprocessors like Tiger Lake to allow laptop makers greater flexibility in how they choose to “clock” them, or at what frequency they’re assigned to run. A laptop that uses a specific processor could run 37 percent faster than a second laptop that includes exactly the same chip, Intel executives say.

That means laptop buyers will have to look harder at actual performance reviews with comparative data to understand what they’re getting.

The problem actually cropped up earlier, as Intel moved into its prior (10th-gen) Ice Lake chips. But Intel executives highlighted it during its Tiger Lake launch as something to watch out for. And it all goes back to how laptop microprocessors have evolved over time.

Intel

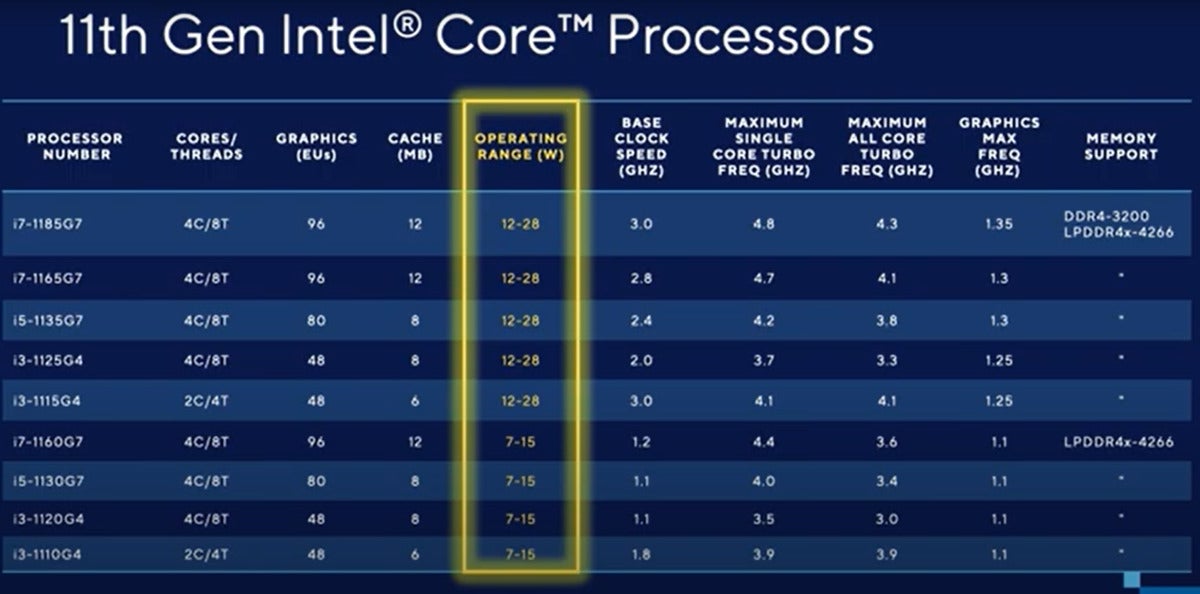

IntelThis column in Intel’s “Tiger Lake” list of processors is a subtle tipoff that Intel has moved away from its limited thermal-design-power metric that has existed for decades.

No fixed frequencies

Traditionally, chips have carried thermal design power (TDP) specifications, defining the power draw and clock speeds at which the chip could safely operate without overheating. Laptops had to manage and sometimes throttle their power demands to keep the chip within certain thermal limits. If a chip exceeded that for some reason, the laptop could throw errors or crash.

Over time, Intel (and AMD) began adding “turbo” capabilities, allowing the chip to exceed its rated voltage through overclocking for a short time, until a risk of overheating forced it to slow down yet again. Intel processors now typically provide single-core turbo modes, all-core turbo modes, and even cherry-pick select cores for overclocking tasks.

Notebooks typically don’t run at a fixed frequency, but bounce up and down depending on the demand. Some call the standard level PL1 and the turbo mode PL2, and refer to a third number, tau, as the time a processor core can spend in a boosted state.

With Tiger Lake, Intel has stopped defining its chips in terms of thermal design power, now defining just an “operating range” in watts, explained Ryan Shrout, chief performance strategist for Intel and senior director of client technical marketing. Intel’s Tiger Lake chips designed for laptops (the UP3 family), now have an operating range from 12 to 28 watts. That gives a laptop maker the option of shipping a lower-performance 15W notebook that emphasizes long battery life, or running it at 28W to trade battery life for greater performance.

Intel

IntelDepending on how the laptop is configured, a Tiger Lake chip can vary widely in performance.

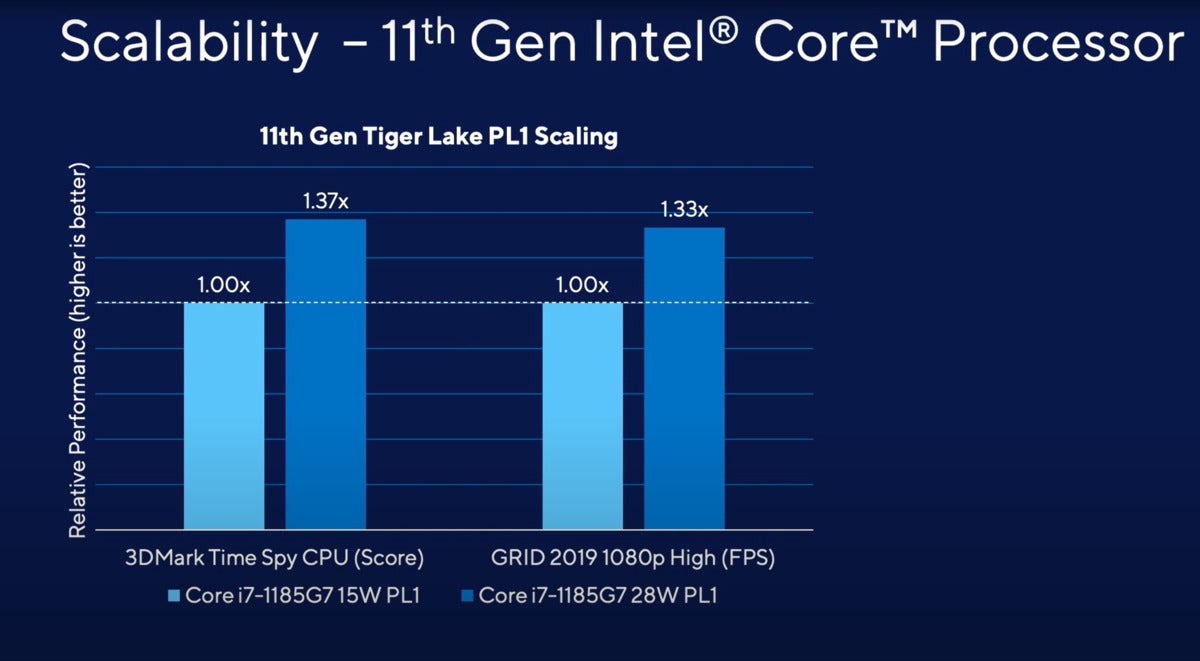

Under these new operating ranges, Shrout said, you could buy a laptop with a Core i7-1185G7 chip inside, configured by the vendor to consume 15 watts. It would run a game like Grid 2019, a racing game, at a given frame rate. But a second laptop with an identical Core i7-1185G7 chip inside, configured to run at 28 watts, would run the game 33 percent faster.

How fast is my laptop? Only testing will tell

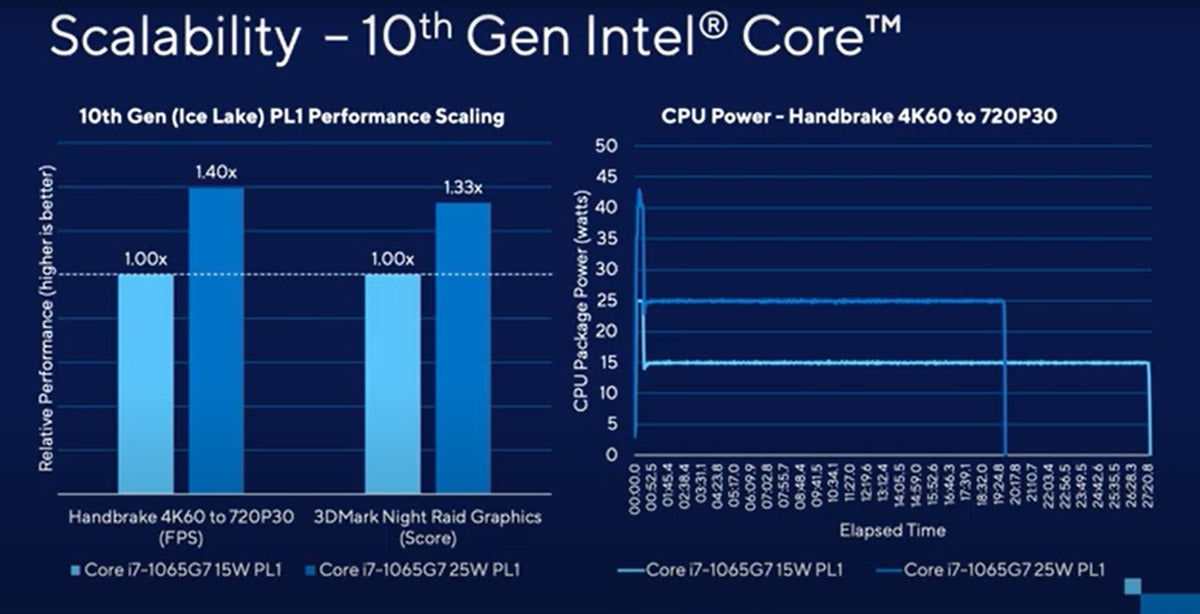

The same issue existed in the prior Ice Lake generation, but it was more pronounced, as Shrout showed in test data shared at a press briefing. At right below are test results using the CPU-centric HandBrake conversion utility. A Core i7-1065G7 running at 15 watts could, in turbo mode, briefly keep up with the same chip running at 25 watts in a non-turbo PL1 state.

Intel

IntelThe problem existed in the 10th-gen “Ice Lake” generation, but the industry still isn’t doing anything about it. Again, the same chip is being compared at different power levels.

Otherwise, in that test and others (see bar charts at left above), there was up to a 40-percent performance difference. And that’s perfectly acceptable, Shrout said.

“The TDP is the same on the spec sheet for these different systems, but because of the cooling implementation, the tuning from the OEMs and the partnership from Intel, and the target audience and the use cases of these systems, the performance can actually be quite different across different workloads,” Shrout said.

“No single design is best in our view, but each design allows for different focuses, and product design choices,” Shrout said.

In this case, however, the interests of consumers and laptop makers are at odds. Laptop makers get the flexibility, but consumers get no insight into whether their laptop is running at a lower or higher performance state.

“The power of Tiger Lake is its scalability, and the dynamic range of the product,” Shrout said. “We don’t enforce some kind of branding indication, or what thermal design, or what power delivery design,” Shrout said. “So it really will come down to the performance reviews and narratives to determine what you’re running at.”

Intel

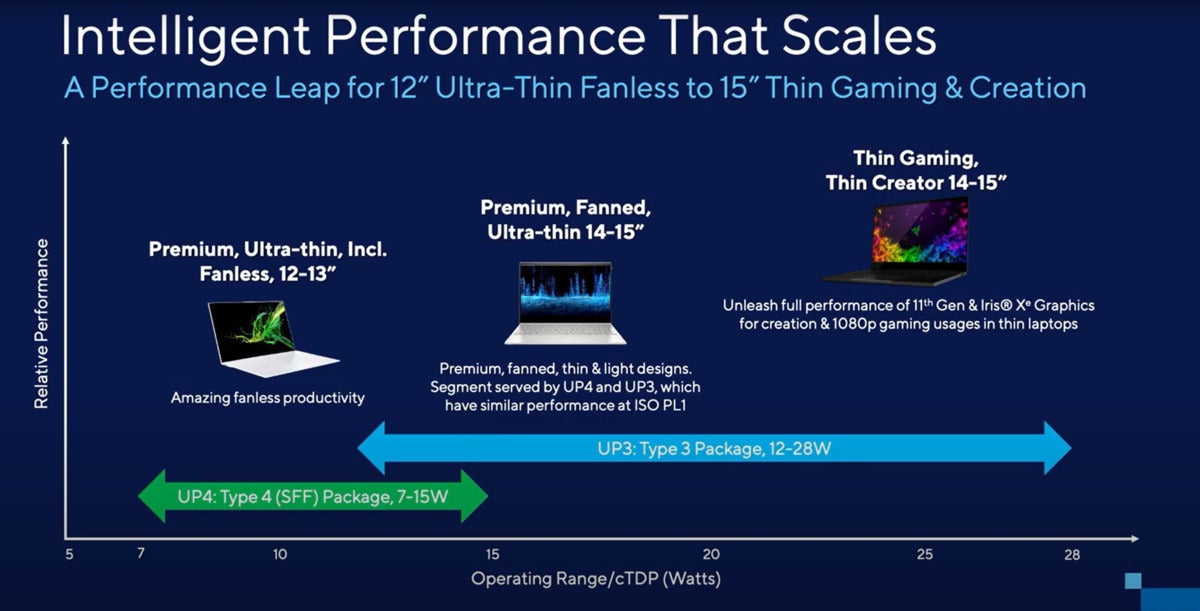

IntelIntel is making the argument that the same Tiger Lake chip is actually being used in a range of devices from tablets through gaming PCs, just packaged slightly differently and at different power levels.

Shrout said that Intel did not plan to distinguish further at what power state a chip would run. Intel uses a Core i3/i5/i7/i9 branding structure to tell consumers what performance to expect from its various product families, and it’s launched its “Evo” brand to indicate premium notebooks. Consumers and reviewers are free to use various software tools to determine a notebook’s power settings, Shrout said, even as he encouraged customers to keep their eyes on the prize.

“At the end of the day, the performance is what matters most,” Shrout said.

It’s just that, as Intel admits, you won’t know what sort of performance to expect until that laptop is tested.

Related Intel Tiger Lake stories:

[ad_2]

Source link