[ad_1]

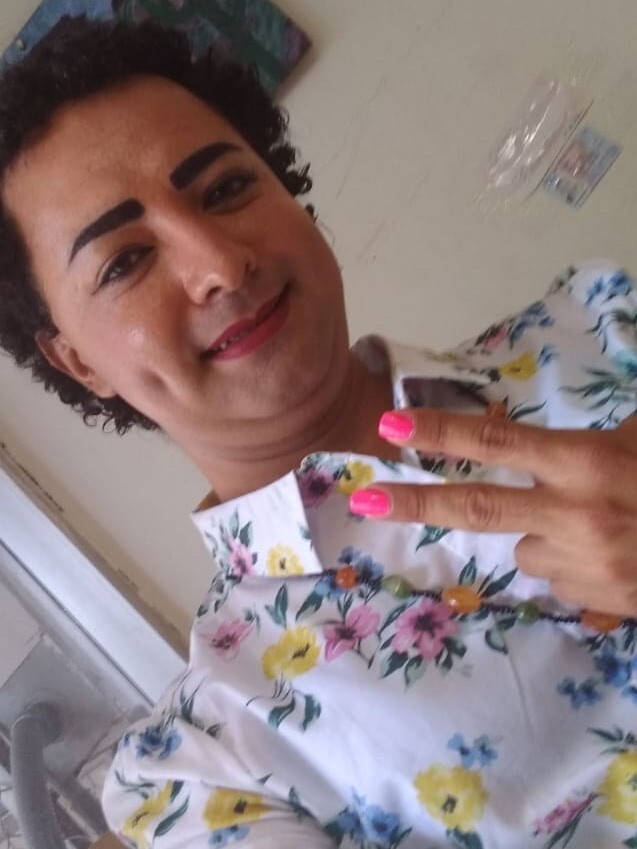

Shakira Najera Chilel left Guatemala and traveled through Mexico to seek asylum in the U.S. She has been at the Eloy Detention Center in Arizona since last year and it is among the hardest hit by the coronavirus pandemic.

Shakira Najera Chilel

hide caption

toggle caption

Shakira Najera Chilel

Shakira Najera Chilel left Guatemala and traveled through Mexico to seek asylum in the U.S. She has been at the Eloy Detention Center in Arizona since last year and it is among the hardest hit by the coronavirus pandemic.

Shakira Najera Chilel

Shakira Najera Chilel feels like she’s faced death before.

As a transgender woman, she dealt with violence and harassment back home in Guatemala and on her journey through Mexico to seek asylum in the U.S. She arrived last year and has been detained at the Eloy Detention Center in Arizona ever since.

“Now I find myself face-to-face with death again; that’s how I feel,” she said in a phone interview from inside the detention center. “Because you can either be a survivor or die from COVID-19.”

The number of immigrants with COVID-19 in Immigration Customs Enforcement custody has risen rapidly. More than 2,700 detainees nationwide have tested positive, according to ICE data, and the Eloy detention facility is among the hardest hit by the pandemic. More than 200 detainees there have tested positive — a tenfold increase in less than three weeks.

Some of them were in Chilel’s cell block.

“They took them out of their cells because they said they felt like they couldn’t breathe and they had a fever and body aches,” she said.

Social distancing in detention is difficult, if not impossible. Even the officials who run these facilities expressed concern about that when surveyed by the Homeland Security Inspector General’s office in April.

In the report, released last week, they also expressed concerns about not having enough hand sanitizer and protective gear — or even medical staff and quarantine space in case of outbreaks.

American Civil Liberties Union Senior Staff Attorney Eunice Cho said they were right to worry.

“These are warnings that have been inevitable from the very start and exactly the reason why ICE should have, and should continue to, release people, especially those who are medically vulnerable to COVID-19, to prevent a humanitarian disaster,” she said.

ICE says it follows guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for COVID-19 testing and medical care. The agency also says it has ramped up testing and released hundreds of medically vulnerable detainees.

But critics say those measures fall short. Former Homeland Security health adviser and agency whistleblower Dr. Scott Allen testified to Congress in June. He said “gaping holes” in testing guidelines and ICE’s failure to significantly reduce population size have made these facilities hot spots for the virus.

“The fact is, in the real world, use of those guidelines has been associated with failure,” he said.

Immigrant advocates and lawyers argue the best way to stop the contagion in detention is to release the detainees, many of whom have only been charged with civil violations.

Last Friday, U.S. District Court Judge Dolly M. Gee in California ordered ICE to release children who have been held in family detention centers for more than 20 days. She cited concerns about the spread of the coronavirus and said the children must be released by July 17.

Other lawsuits are pending. Laura Belous is with the Arizona legal aid group Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project. The group, along with the ACLU, has sued for the release of more than a dozen medically vulnerable clients held at Eloy and at the La Palma Correctional Center a few miles away.

“There’s no way to be safely detained during a pandemic,” Belous said.

ICE spokeswoman Yasmeen Pitts O’Keefe said the agency does not comment on pending litigation, and that releases are being reviewed on a case-by-case basis. She attributed the surge in COVID-19 cases at Eloy to an increase in asymptomatic testing, and said ICE has restricted intake of new detainees at the facility.

In a series of letters to immigrant advocates and lawyers, detainees from La Palma say they’ve been forced to clean medical wards and common areas without enough protective gear. At Eloy, detainees say they don’t have regular access to showers.

Immigrants at both facilities with conditions like diabetes, cancer and hypertension say they’re scared that COVID-19 will kill them.

Belous said complaints have continued even after a district court judge in Arizona ruled the facilities must make changes to keep people safe.

That ruling came in a separate lawsuit filed in April by the Florence Project and ACLU for the release of eight detainees with serious underlying health conditions. Lawyers argued in that case that preventative measures taken at La Palma and Eloy did not adequately protect detainees from COVID-19.

“Almost every conversation I’ve had with clients has resulted in them sort of saying, ‘I’m scared, I’m worried, I can’t be here anymore,'” Belous said.

CoreCivic, the prison company that runs Eloy and La Palma, insists that it can keep detainees safe. Spokesman Ryan Gustin said detainees do have access to protective gear, showers and testing, and they aren’t forced to work.

The facilities have a combined capacity of around 4,500, but Gustin said they are under capacity, so detainees can practice social distancing.

La Palma reported its first case of COVID-19 among detainees in April. More than 90 detainees have tested positive for the virus as of today.

And employees at both facilities also have been impacted. Gustin said 83 CoreCivic staff members at Eloy Detention Center and 21 at La Palma have tested positive as of June.

Meanwhile, immigrants like Chilel are terrified.

She said digestive issues she’s had since arriving at Eloy have made it hard to eat. Lately, she’s also had headaches and bad body aches. But she’s been waiting for weeks to see a doctor.

“They have told us that if we feel bad, they will send us to a doctor that moment … but it’s a lie,” she said. “It’s frustrating. I always feel like I’m between life and death.”

Immigrant advocates argue LGBTQ immigrants like Chilel face higher risks in detention, even in normal times. Her lawyers have filed a request for humanitarian parole and are exploring other legal avenues to get her released.

[ad_2]

Source link