[ad_1]

1News presenter Melissa Stokes speaks to Sandra Coney, one of many journalists who broke the story on an experiment within the Nineteen Sixties and ’70s involving girls with untreated cervical abnormalities at National Women’s Hospital. The watershed inquiry that adopted endlessly modified how girls’s well being can be handled in New Zealand.

Sometimes, the tales that make the information go on to have large ramifications, not only for the people concerned. This is a type of tales.

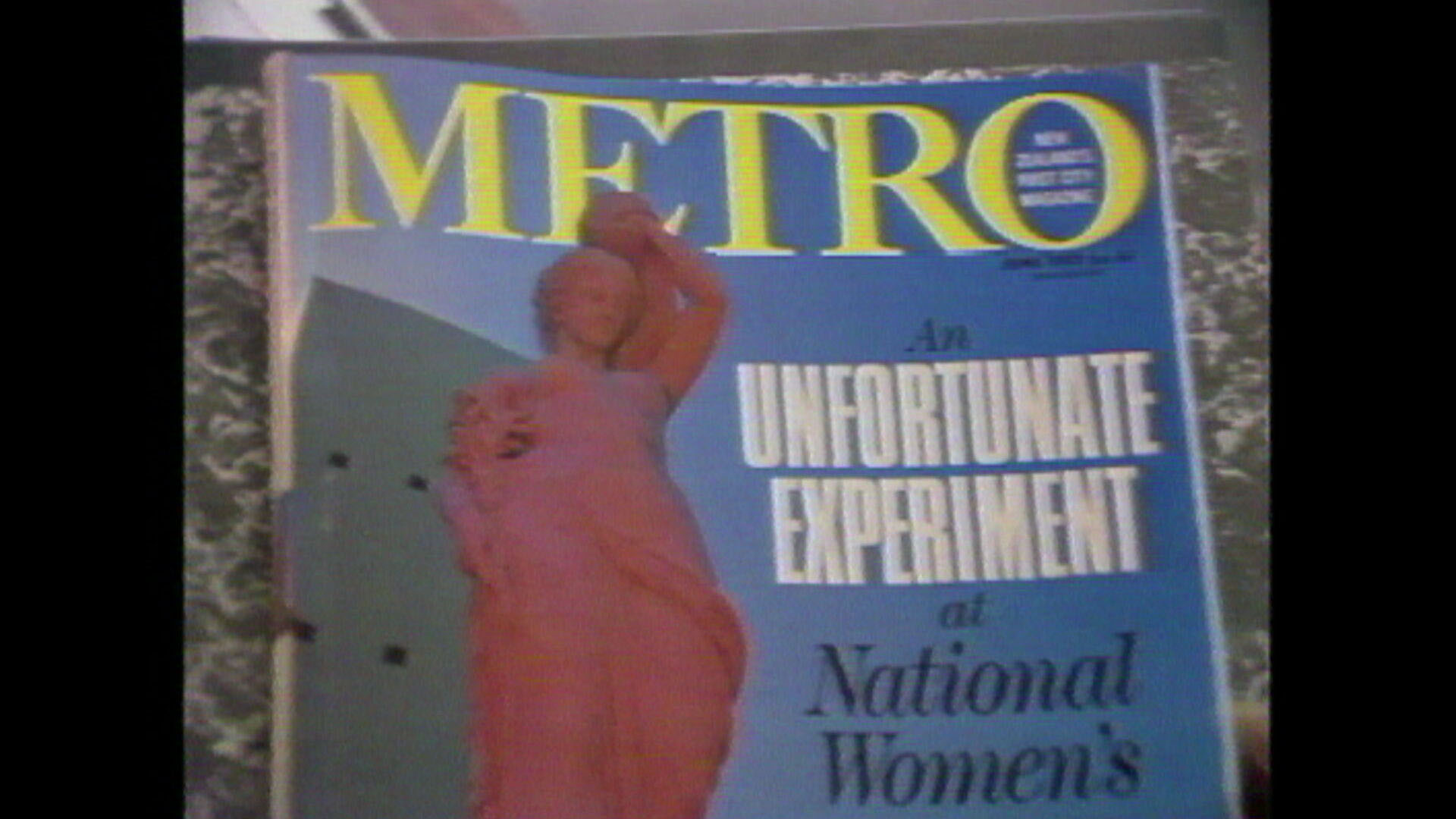

In 1987, after following a tip-off and dealing on a narrative for a number of years, journalists Sandra Coney and Philida Bunkle revealed The Unfortunate Experiment.

Sandra Coney remembers how the story would go on to affect medical practices on this nation began.

“We had a whisper from a friend who was at the Auckland medical school about a study that was going to come out that showed that women had not been properly treated with abnormal smears. We knew it was serious right from the beginning – it was just putting together how it had happened.

“One of our massive worries was that nobody would wish to publish it, that they might be scared to place it on the market.”

But once “on the market”, it became a huge story in New Zealand history.

The story alleged that women were being used as guinea pigs in an experiment at National Women’s Hospital.

A professor, Herbert Green, ran a research programme in the 1960s and 1970s. He believed what was called carcinoma in situ would, in most cases, rarely progress to invasive cancer if left untreated. To test this, he followed women with cervical carcinoma without definitively treating them.

The article alleged the hospital knew about the research, but patients were never told.

“The key factor was that the ladies had been by no means requested in the event that they needed to be in a trial, they had been by no means given choices about remedy now or delaying it, they had been by no means given choices about the kind of remedy,” Coney said.

“They had been simply introduced again repeatedly through the years to look at what the lesion was doing on their cervix however they weren’t accountable for their very own well being.”

The response to the article was swift, with a commission of inquiry called within weeks.

Chief District Court Judge Silvia Cartwright was named as the person who would preside over what became known as the Cartwright Inquiry.

The name may sound familiar to many of you. Dame Silvia, as she became in 1989, went on to an illustrious and storied career.

She was our Governor-General for five years from 2001 and was one of of only two international judges at the Cambodian War Crimes Tribunal.

She was charged with finding out if there had been a failure to treat women adequately for early signs of cancer.

For five months, questions about medical ethics and patients’ rights were considered, and more than 140 witnesses were called.

Coney was named in the terms of reference in the inquiry, turning up every day.

“It was actually heartbreaking studying a few of these since you may see the hole between what the medical doctors had been doing and what the ladies and their households thought was taking place,” she said.

“They thought they had been in the very best of palms. They thought their greatest pursuits had been being taken care of. They had been within the prime hospital with the highest medical doctors and they might be cared for.”

Looking at the footage TVNZ has from around this time, I can tell it was a story that hit big.

There’s footage from inside the Minister of Health Michael Bassett’s office when just days after the article was published, he called an inquiry. Newsgathering has changed since then – journalists wouldn’t all be crowded into his space like that.

There’s footage from days and days of the inquiry as key players took the stand. We see Green being questioned, and Coney carrying piles of notes into the hearing.

The inquiry findings were announced in the Beehive where so many important government announcements are made. You’ll recognise it in our report from all the 1pm Covid-19 briefings.

Judge Silvia found there had been a failure to adequately treat a number of women with carcinoma and for a minority of women, that resulted in the development of invasive cancer.

The Cartwright Inquiry and the recommendations it made contributed to sweeping changes in the medical industry, leading to a code of patients’ rights, a Health Commissioner, and what became the national cervical screening programme.

The article Coney worried would never be published ending in unprecedented change.

“Women nonetheless come as much as me and inform me their tales and say ‘thanks for what you probably did, it saved my mom’s life’, or aunty’s life’ so that is what actually counts.”

[adinserter block=”4″]

[ad_2]

Source link