[ad_1]

Opinion: how has Irish identity and culture been represented by performances involving sport onstage?

In 1994, National Geographic magazine published a detailed article on Ireland. A view of Irish society on the cusp of the Celtic Tiger, the piece was illustrated with numerous photos which included scenes of intercountry hurling matches, photos of U2 playing to sold-out concert arenas and an image of a group of Macnas performers in Galway.

At the heart of the article was an examination of how Ireland was performing in terms of economics, employment, industry, tourism and culture. Sport, in particular, has been a lens through which Ireland is viewed internationally. Sport and its portrayal on the Irish stage has also allowed Irish culture to pivot into another form of performance. As we perform “for the parish” or “for the flag”, these symbols of identity are further represented in the sports we play. When sport meets theatre, how has Irish identity been represented or challenged through performance?

Ireland has traditionally marketed itself internationally on its culture and heritage and on how it performed its ‘Irishness’. The Tóstal festivals, for example, began in the 1950s as a tourism initiative aimed at luring the Irish diaspora into holidaying in Ireland during the Easter break. Sporting imagery of horse-racing, golf and hurling adorned the advertising posters and Ireland was marketed as a space for leisure, recreation and sport.

From the Hodgson Collection and RTÉ Archives, film shot by Norman Hodgson showing the opening of An Tóstal in Dublin in 1953.

These festivals were branded and advertised as cultural events and featured pageants such as the Pageant of Saint Patrick and the Pageant of Cúchulainn. The latter utilised the image of the fallen Cúchulann modelled on the sculpture “The Death of Cúchulainn” by Oliver Sheppard (which can be found in the window of the GPO in Dublin today). These mass-participation events included casts of hundreds, bringing local communities into the spectacles staged at open-air venues like Croke Park. The symbolism wasn’t lost on holding such events steeped in the imagery of Irish nationalism, sporting identity and religious sentiment.

Sport in particular became a motif through which both Irish culture was displayed and performed and a way to challenge authority in contemporary Ireland. In 1987, the 35,000-strong crowd that gathered at Castlebar for the Connacht football final between Mayo and Galway were treated to another spectacle. Produced by Macnas, The Big Game saw a mock Gaelic football game staged between Mayo and Galway. The “players” wore large oversized heads (some modelled on the actual Galway team players) as they played out a “match” on the pitch.

The character of then Bishop of Galway, Eamonn Casey, played by Rod Goodall, was also present. Macnas’ portrayal of the bishop, who performed the ceremonial throw-in of the ball to start the match, was a nod to the then presiding influence of the Catholic Church in Ireland, particularly in rural Ireland and within sporting communities and institutions, such as the GAA. In 1987, Casey was a household name in Ireland, but it was still prior to the fallout over his fathering a child. The Big Game pre-empted the slow break of influence of the Church in Ireland over the coming decade.

From RTÉ Archives, Tommie Gorman reports on the Macnas Big Game performance at the Connacht football final in 1987

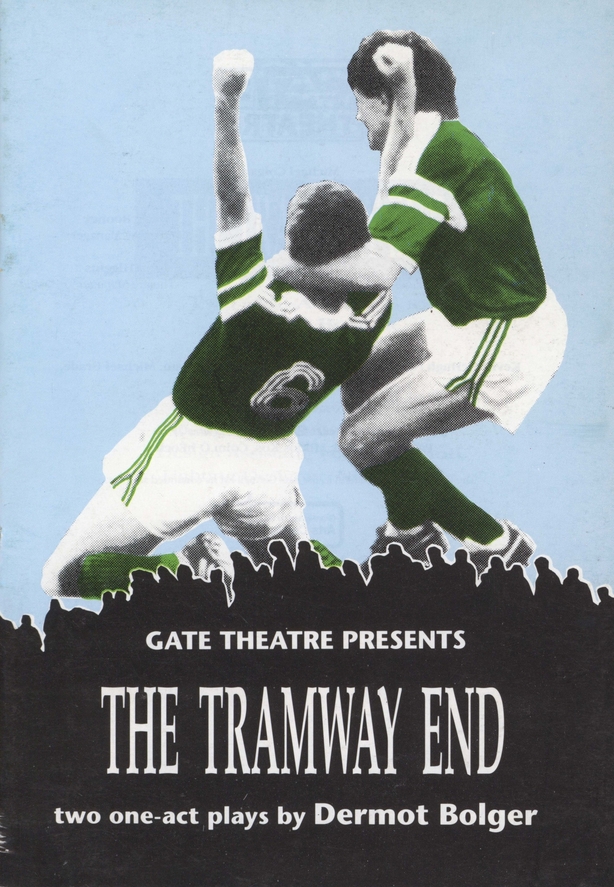

Performed as part of a double-bill of plays called The Tramway End, Dermot Bolger’s play In High Germany was produced at the Gate Theatre, Dublin in 1990. Set during the European football championships two years earlier, it takes place on a railway station platform in Hamburg and features a Jackie’s Army group of soccer fans and old friends reuniting to follow the Irish team on their European odyssey.

The play succinctly draws out the complexities of identity through class, culture and sport, where some Irish living abroad only seem to be able to participate in or perform their Irishness as part of a traveling community of football supporters. The Irish team, led by an Englishman in the form of the late Jack Charlton, and whose star players were largely born in Britain to Irish emigrants, broke down cultural and class barriers, from the terraces to housing estates around Ireland. They also allowed new possibilities for Irishness (and Anglo-Irishness) to emerge and be celebrated.

Billy Roche’s 2008 play, Lay Me Down Softly, offered a ring-side seat into Delaney’s Travelling Roadshow and the often lawless world of 1960s travelling carnival shows and prize-fighting. What happens between the ropes is pure performance as brash personas are tempered by bruised and crumbling bodies, impacted by an unforgiving life on the road. Boxing becomes a metaphor for the wider family and personal relationships at risk of crumbling under pressure. The fighting on display is often internal and psychological and asks the question, ‘what do you fight for?’

In 2010, the country was still processing the details of the report of the Commission to Enquire into Child Abuse (the Ryan Report). We had also seen the broadcast of documentaries such as States of Fear (1999) by journalist Mary Raftery and Dear Daughter (1996) directed by Louis Lentin and telling the story of Christine Buckley.

In response to these reports and the testimony by survivors of abuse, the Abbey Theatre programmed a series of events called The Darkest Corner. The series included Christ Deliver Us!, a new play by Thomas Kilroy which was an adaptation of the 19th century play, Spring Awakening by Frank Wedekind. It was set in a boarding school in the midlands in the 1950s where the clergy ruled the school and the boys who lived and studied there with a loose fist. For many of the boys, hurling was the main outlet away from lessons and endless catechism.

In a remarkable choreographed scene, the main stage of the Abbey became a hurling pitch, where the boys jostled and played a hurling match. Later in the play, the movement of the boys changes from perceived masculine pursuits of hurling before a cheering school to the private moment of a serene but equally athletic dance scene between two schoolboys. In that moment, the homosexual desires of the boys could be explored away from jostling crowds, creating a scene at odds with the public celebration and performance of (usually) male sporting heroes.

In 2014, the Irish Government held an event at the GPO in Dublin to launch as the plans to commemorate the 1916 Easter Rising as part of the Decade of Commemorations. A promotional video, “Ireland Inspires 2016”, was released to accompany the planned commemorations of 1916, but it curiously didn’t mention the historical events, participants or contexts to the 1916 Easter Rising. Instead, well produced footage of the expanding digital dockland hubs of Facebook and LinkedIn, the Long Room of Trinity College Dublin and typical scenes of Irish landscape featured, all highlighting the performance of Irish post-Celtic Tiger economic rejuvenation and success.

Ireland Inspires 2016

A timeline of notable Irish figures from politics to the arts was also featured. The only woman who featured on the video across a century of Irish notable figures was Olympic and world champion boxer, Katie Taylor. Brian O’Driscoll also made a try-scoring cameo, showing how our sporting successes are viewed as evidence of our national success and also our national identity on a world stage, even in place of the state itself.

When it comes to Irishness, sport is still a means by which identity is performed. As political jargon frequently reminds us, clichés such as “pulling on the green jersey” or “playing senior hurling” are commonplace in the national interest. In the performance of sport through theatre, we become an audience in a sporting theatre of a different kind, one which still raises emotions, draws people together and enables us to look at our identity from a different vantage point.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ

[ad_2]

Source link