[ad_1]

Noah Creshevsky was an egalitarian who believed in humility in dying.

Courtesy of David Sachs

cover caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of David Sachs

Noah Creshevsky was an egalitarian who believed in humility in dying.

Courtesy of David Sachs

This is the second story in The Unmarked Graveyard: Stories from Hart Island collection from Radio Diaries. You can take heed to the subsequent installment on All Things Considered subsequent Monday, and read and listen to previous stories in the series here.

When Noah Creshevsky came upon he had bladder most cancers in 2020, he determined to not have surgical procedure. He was 75 and did not need to reside with a man-made bladder.

“He thought it was the beginning of a slope and he didn’t want to go down it,” says Creshevsky’s husband, David Sachs. “I remember his surgeon was stunned because no one had ever declined [treatment]. Everyone wants to grapple for every minute of life.”

So Creshevsky knew he was going to die. But he did not know if it could be “three more weeks, three more months, three more hours,” says Sachs. “We didn’t know.”

Sachs and Creshevsky had been dwelling collectively for 42 years. They discovered the identical motion pictures humorous, they learn the identical books. “It was a remarkably satisfying relationship,” Sachs says. “So I was lucky.”

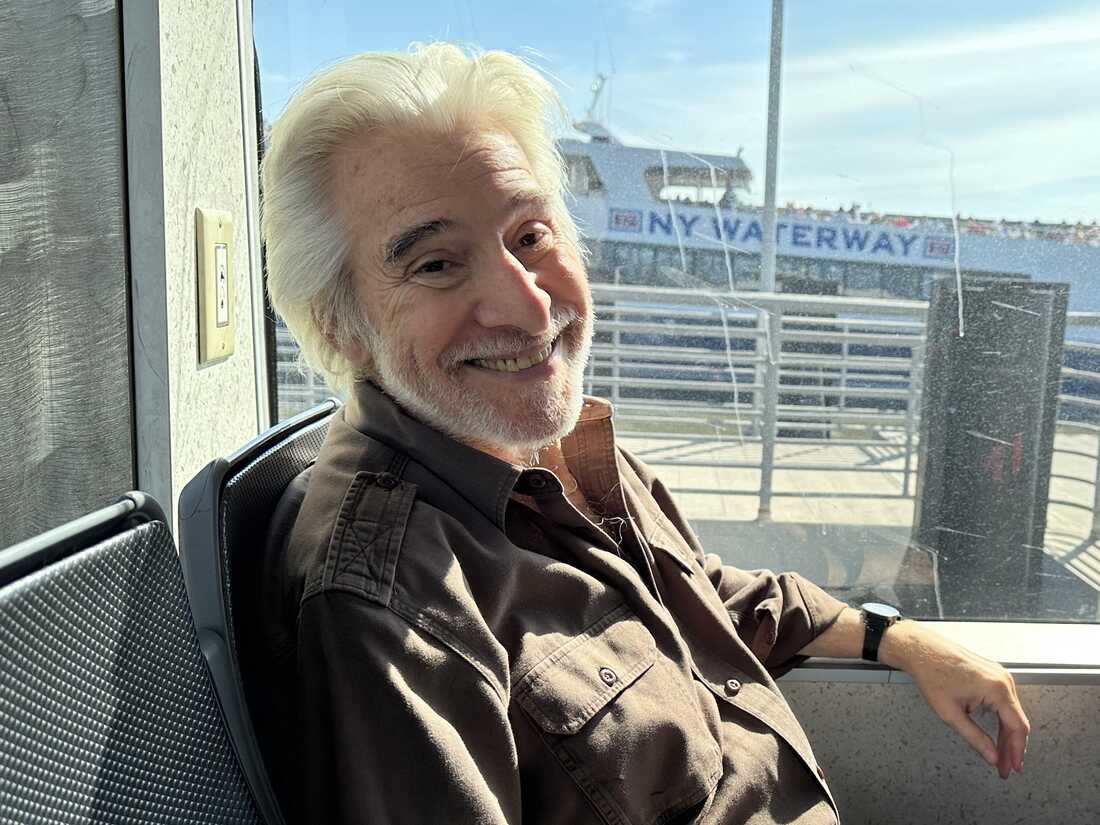

David Sachs in 2023.

Courtesy of David Sachs

cover caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of David Sachs

David Sachs in 2023.

Courtesy of David Sachs

Sachs was a trainer and e-book editor. Creshevsky was an experimental digital composer. He known as his music “hyperrealism.” He was additionally a beloved trainer at Brooklyn College.

Early in his profession, Creshevsky had studied composition with among the most distinguished figures in trendy music, together with conductor Nadia Boulanger. He initially imagined he could be a live performance pianist, however then he fell in love with the world of digital music and his dream modified.

“He realized what music could be,” says Sachs. “It needn’t be someone sitting at a keyboard or playing a string. But it could be something wildly imaginative.”

“Strategic Defense Initiative” by Noah Creshevsky

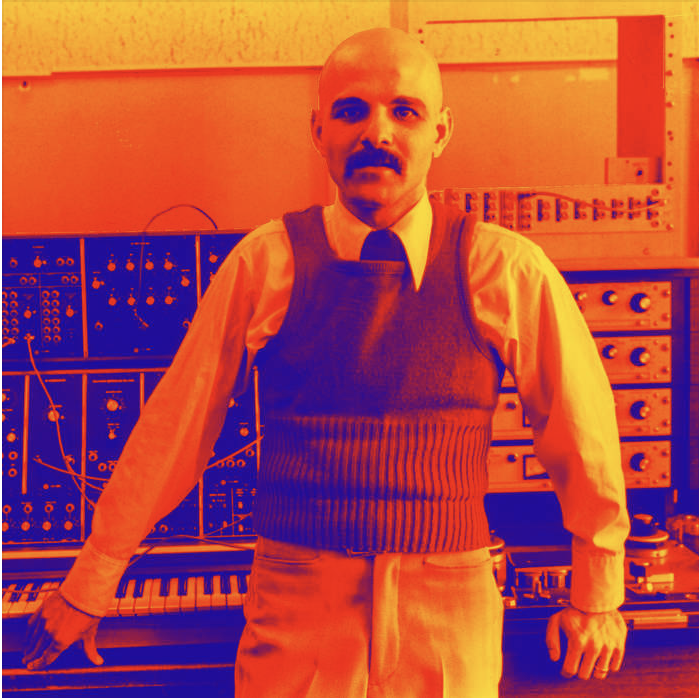

Creshevsky in 1985 together with his Moog synthesizer.

Courtesy of David Sachs

cover caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of David Sachs

Creshevsky began by taking acquainted sounds and taking part in with them — stretching, layering, placing them collectively in sudden methods. He would do subject recordings, strolling round with a tape recorder and capturing sounds on the road.

“He loved walking down the street in Manhattan where you could hear languages, not only that you didn’t speak but that you didn’t even recognize,” Sachs says. “He loved the idea of a sound that you couldn’t quite identify. Squint your ears, you know.”

“Tomomi Adachi Précis” by Noah Creshevsky

Then, as Creshevsky bought older, his music turned extra severe, says Sachs: “A little less playful. The way life gets a little less playful as you get older. We become more and more aware of the sadness, of the inevitable termination that awaits us all.”

“Sleeping Awake” was the final piece Creshevsky accomplished earlier than he bought sick.

“Sleeping Awake” by Noah Creshevsky

Knowing they solely had just a few extra months collectively, Sachs says they tried to not speak an excessive amount of about dying. “He didn’t want to see me crying or upset,” Sachs says. “So I had to put on a happy face. Everything hunky dory.”

But they did speak about what Creshevsky wished to have occur to his stays after he died. One choice was to have a conventional burial, the best way his dad and mom had, in a household plot. Creshevsky was Jewish, however “nothing seemed to him more vulgar than fetishizing death with real estate,” Sachs says. “You know, a stone, a marker, a mausoleum — he just didn’t want a part of it.”

Then they realized about Hart Island.

Hart Island is New York City’s public cemetery, typically referred to as a Potter’s Field. More than 1,000,000 persons are buried there, in mass graves, every with about 150 coffins inside. There are not any headstones or plaques.

There is a broad vary of people who find themselves buried on the island – folks whose households could not afford a non-public burial; individuals who could not be recognized; and individuals who died in varied waves of epidemics that swept town. In the Nineteen Eighties it was AIDS, and most just lately, COVID-19. Close to 10% of New Yorkers who died of the coronavirus had been buried on Hart Island.

It’s not a spot many individuals select to be buried. But Sachs says Creshevsky was drawn to the thought of being buried collectively.

“The simplicity, the anonymity, the humility. And it was on the water, which he loved,” Sachs says. “For someone who was such an egalitarian, who believed genuinely in everyone’s equality, it was the right decision, for him.”

Creshevsky in his studio in 2015.

Courtesy of David Sachs

cover caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of David Sachs

Creshevsky in his studio in 2015.

Courtesy of David Sachs

They did not inform anybody about their plan. But when Creshevsky’s hospice nurse came upon, she was upset. She had a picture of Hart Island as a “garbage dump,” says Sachs, “for only the unknown who no one cared about.” But Sachs says, in the long run, she got here to appreciate the meaningfulness of the choice.

“A lot of people, I think, look at death as a way to extend your ego,” Sachs says. “Either your monument or the way in which you’re buried. And ego stops with death.”

Sachs says that Creshevsky puzzled about life after dying. “He didn’t believe in reincarnation in the literal sense. Like, I’m going to come back as Elizabeth Taylor,” says Sachs. “But I may come back as a tree. I may come back as a breath. Who knew?”

The album cowl for The Tape Music of Noah Creshevsky, 1971-92.

Courtesy of David Sachs

cover caption

toggle caption

Courtesy of David Sachs

The album cowl for The Tape Music of Noah Creshevsky, 1971-92.

Courtesy of David Sachs

Creshevsky and Sachs ended up having three extra months collectively. “We had a wonderful time,” says Sachs. Then Creshevsky began to get weak and delirious. “Not the fun kind of delirium where you’re high or drunk, festive and funny. But the sad kind, where you don’t know who you are. It was hard, man, it was hard.”

Sachs remembers their final evening collectively. He had been up a number of nights with Creshevsky, and he was drained. He kissed his husband good evening, the best way he did each evening for the previous 42 years. And within the morning Creshevsky was lifeless.

“You know when someone is dead,” says Sachs. “It’s not only that you poke them and they don’t get up. But you know. You have a feeling that that person is dead.”

Sachs says it was quiet for a very long time, after which he was left alone within the residence. “And that was how it ended.”

It’s been greater than two years since Creshevsky died. But Sachs says he nonetheless finds it troublesome. Friends typically ask him how he feels about Creshevsky’s choice to be buried on Hart Island; whether or not he misses having a conventional gravesite the place he may simply go to. Sachs says, unequivocally: No.

“I mean, I still think of Noah every day, every minute. This whole house we lived in together all those years, right? That bed that I sleep in every night is the bed in which he died,” Sachs says.

“I wake up sometimes and I see he’s not in bed with me, and my first instinct is to call to him, assuming he’s in the other room. And then I realize, more or less quickly, that, no, he’s not there. And that hits you sometimes like a ton of bricks. He’s not in the other room or in another city. He’s not anywhere. And then, almost immediately, a more calming realization sinks in: he’s everywhere.”

A ultimate observe: Sachs says he is determined that, when the time comes, he can even be buried at Hart Island.

“In Memoriam” by Noah Creshevsky

This story was produced by Joe Richman of Radio Diaries. It was edited by Ben Shapiro. Production assist from the workforce at Radio Diaries: Nellie Gilles, Mycah Hazel, Alissa Escarce, Lena Engelstein, and Deborah George.

This story is the second in a collection known as The Unmarked Graveyard: Stories from Hart Island. You can discover a longer model of the story, and different tales about Hart Island, on the Radio Diaries Podcast.

[adinserter block=”4″]

[ad_2]

Source link