[ad_1]

Former Chinese President Jiang Zemin gestures as he thanks reporters for coming to a photograph alternative in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People on Sept. 19, 1997. Jiang died on Nov. 30 at age 96.

Will Burgess/Reuters

cover caption

toggle caption

Will Burgess/Reuters

Former Chinese President Jiang Zemin gestures as he thanks reporters for coming to a photograph alternative in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People on Sept. 19, 1997. Jiang died on Nov. 30 at age 96.

Will Burgess/Reuters

LONDON — One Sunday morning in 1997, Chinese officers invited American reporters to the Great Hall of the People in Beijing to ask questions of Chinese President Jiang Zemin, who died last week at 96. I used to be working for The Baltimore Sun on the time. I headed to Tiananmen Square and handed by means of minimal safety for a uncommon press convention with the chief of the Chinese Communist Party.

Jiang was training for a state go to to Washington to see President Bill Clinton. China wished admission to the World Trade Organization and Jiang hoped to make an excellent impression on Americans. When referred to as, I requested Jiang how he would persuade them that he shared their values. His reply: by assembly them in individual.

As if to emphasise that time, Jiang stopped to talk to me on his means out. There was no translator, nobody between us. I might inform he was nervous. Chinese leaders not often work together with Chinese individuals — not to mention international reporters. Concentrating on his English, which he’d been training, Jiang mentioned Americans can be far more comfy with him as soon as they acquired to know him.

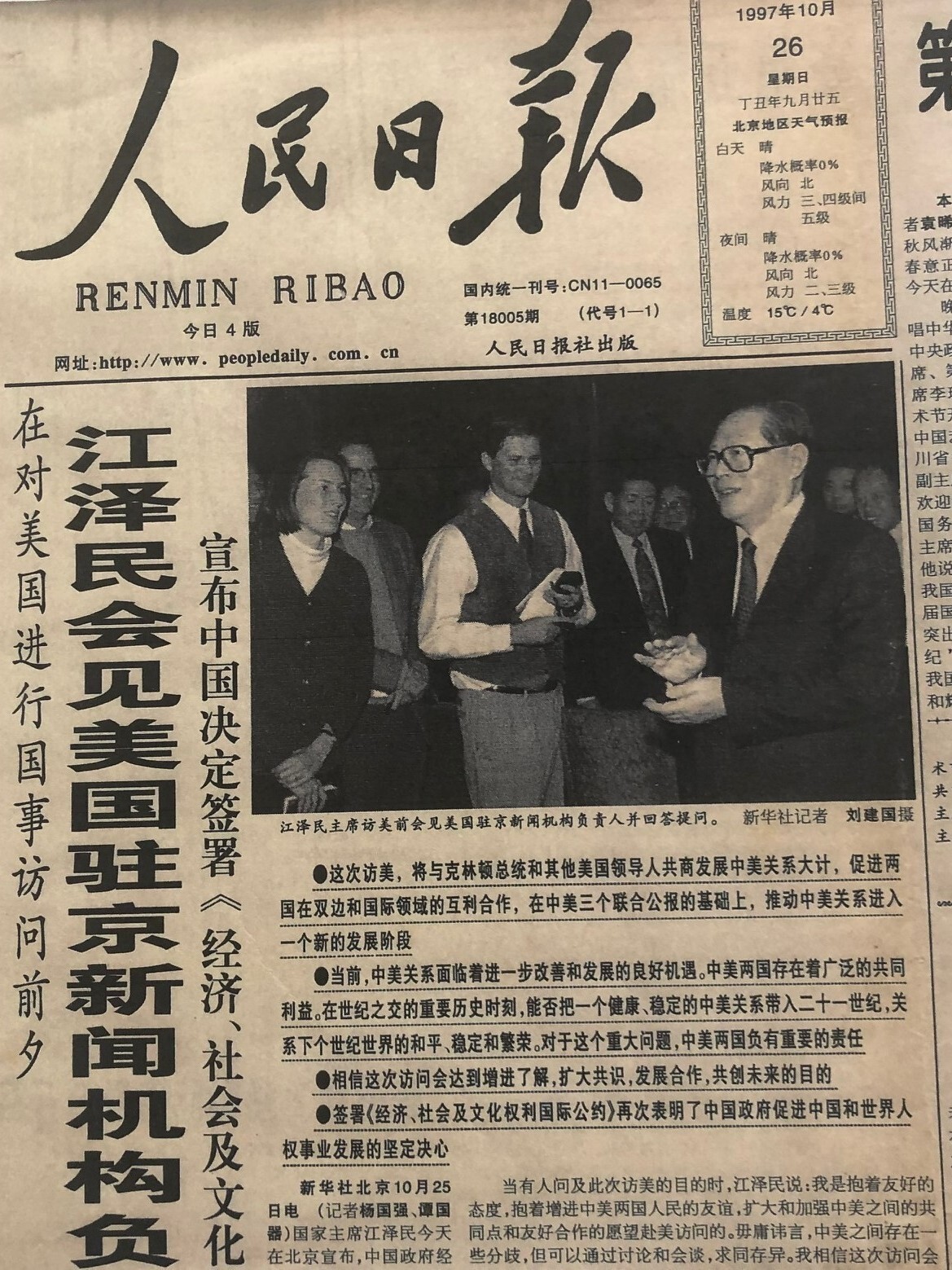

The People’s Daily, the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, displaying Jiang Zemin (proper) assembly journalists, together with Frank Langfitt (heart), on the Great Hall of the People in Beijing in 1997.

Frank Langfitt/NPR

cover caption

toggle caption

Frank Langfitt/NPR

The People’s Daily, the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, displaying Jiang Zemin (proper) assembly journalists, together with Frank Langfitt (heart), on the Great Hall of the People in Beijing in 1997.

Frank Langfitt/NPR

A unique period

On Tuesday, China holds a memorial for Jiang within the Great Hall of the People in a rustic that’s way more repressive than when he left workplace — as required by time period limits — in 2002.

The present chief, Xi Jinping, doesn’t chat with international reporters. Under his rule, the Chinese authorities is extra vulnerable to kicking them overseas. Xi once said of international journalists: “Some foreigners with full bellies and nothing better to do [than] engage in finger-pointing at us.”

The passing of Jiang has each Chinese and foreigners who lived in China within the Nineteen Nineties pondering how a lot the nation has modified within the intervening quarter century.

Despite the smog and the chaotic crowds, I liked dwelling in Beijing again then. Jiang was no political reformer, however China was a dynamic, optimistic nation the place many issues appeared attainable and there was a minimum of some house without spending a dime expression.

In 1998, I lined President Clinton’s go to to Beijing. During a stay televised press convention, Clinton instructed Jiang the federal government had been on the “wrong side of history” to gun down protesters in the course of the 1989 Tiananmen Square democracy demonstrations.

Then President Bill Clinton and Chinese President Jiang Zemin make a toast on the State Banquet in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People on June 27, 1998.

Luke Frazza/AFP/Getty Images

cover caption

toggle caption

Luke Frazza/AFP/Getty Images

Then President Bill Clinton and Chinese President Jiang Zemin make a toast on the State Banquet in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People on June 27, 1998.

Luke Frazza/AFP/Getty Images

“I was very surprised,” Chen Yu, a filmmaker, instructed me at the moment. “This is the most open press conference I’ve ever watched!”

Today, a stay TV debate on Tiananmen — or most something political — is unthinkable. China is way extra repressive now than it was again then. Some of the explanations could appear paradoxical. The Communist Party is far more assured in the present day, but additionally anxious and insecure.

“Why does America love war?”

I left Beijing in 2002 and returned to China in 2011 as a correspondent for NPR primarily based in Shanghai. So a lot had modified whereas I had been gone. Opinion of the United States, which was very excessive after I first arrived within the late Nineteen Nineties, had plummeted. On a taxi trip quickly after I had returned, a cabbie requested: “Why does America love war?” He was referring to Afghanistan and Iraq.

Other Shanghainese complained, rightly, about how lax U.S. lending legal guidelines had triggered the worldwide monetary disaster. Unlike within the late Nineteen Nineties, when the U.S. was at peace and working finances surpluses, neither the Chinese individuals nor leaders in Beijing have been wowed by Meiguo, or the “Beautiful Country,” because the U.S. known as in Mandarin.

In 2016, Britain’s Brexit vote and the U.S. election of Donald Trump additional diminished the West’s standings within the eyes of many Chinese. Some early stumbling by Western international locations to the COVID-19 pandemic boosted the idea of Chinese leaders that their authoritarian system was higher than typically messy democracy.

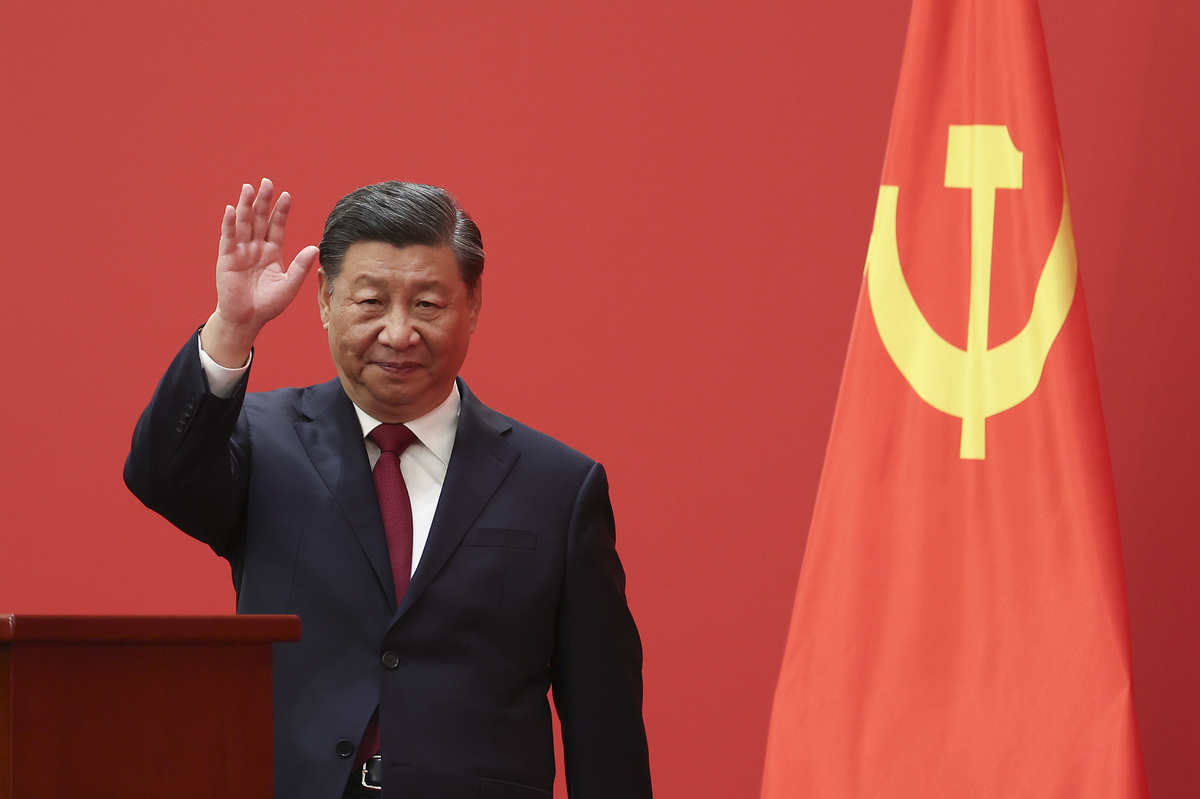

Chinese President Xi Jinping waves throughout between Communist Party officers and Chinese and international journalists on the Great Hall of People in Beijing on Oct. 23.

Lintao Zhang/Getty Images

cover caption

toggle caption

Lintao Zhang/Getty Images

Chinese President Xi Jinping waves throughout between Communist Party officers and Chinese and international journalists on the Great Hall of People in Beijing on Oct. 23.

Lintao Zhang/Getty Images

“As long as we can stand on our own … we will be invincible no matter how the storm changes internationally,” Xi told senior party officials lower than per week after rioters attacked the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, and tried to overturn the U.S. presidential election. “Time and history are on our side, and this is where our conviction and resilience lie, and why we are so determined and confident.”

China was additionally now far wealthier. When I got here to Beijing in 1997, few of my Chinese buddies owned residences or automobiles. In 2002, I moved into an condominium advanced in Shanghai the place most residents have been Chinese and the storage was crammed with BMWs, Lamborghinis and Rolls Royces.

With China’s financial system now the world’s second-largest, the nation was way more highly effective and social gathering leaders did not really feel like they needed to put up with criticism of their system from U.S. officers, as Jiang had with Clinton.

In the 9 years I’d been away, although, corruption had metastasized contained in the Communist Party and it was in serious trouble. Officials have been stealing with each fingers. The rise of social media empowered residents and information organizations to reveal the failures of native and provincial officers.

It was a comparatively hopeful time. Online discourse was thriving, the financial system was booming and China was in some methods extra open than it had been in a few years.

“Things have really changed”

“What kind of an authoritarian state is this?” I questioned.

Xi Jinping apparently questioned the identical factor. After he took over in 2012, the Chinese authorities despatched greater than 1,000,000 officers to jail on corruption prices — together with lots of Xi’s enemies — which helped him consolidate energy and start to rebuild the social gathering’s popularity. Chinese social media platform Weibo was censored and lots of have been delighted with the crackdown.

“I think this anti-corruption campaign is like a shot of adrenaline to the heart of Chinese society,” a salesman named Liu told me whereas sipping espresso at a Shanghai Starbucks.

But when Xi got rid of term limits in 2018 so he might, in idea, serve till dying, it made a few of my Chinese buddies shudder. The social gathering had put time period limits in place to stop management for all times and the excesses that go along with it.

“I was shocked,” one buddy wrote when Xi killed time period limits.

“What scares you,” I requested.

“The possibility of returning to the past, the Mao era,” he responded. “You have to watch whatever you say, so creepy.”

Xi imposed the “zero-COVID” insurance policies that locked down thousands and thousands of Chinese for months and triggered the current road protests wherein a number of individuals, remarkably, referred to as for Xi to step down. That will not occur, however some buddies, who noticed their future in China, are having second ideas.

“Many are desperate to get out,” one instructed me. “Things have really changed.”

Frank Langfitt is NPR’s London correspondent. He served as The Baltimore Sun’s correspondent in Beijing from 1997 to 2002 and as NPR’s correspondent in Shanghai from 2011 to 2016. He is the writer of The Shanghai Free Taxi: Journeys with the Hustlers and Rebels of the New China.

[adinserter block=”4″]

[ad_2]

Source link